It is a trial with many firsts. It’s the first time the Netherlands is prosecuting someone for crimes against Iraq’s Yazidis; it’s the first Dutch case of slavery as a crime against humanity; and it’s the first time in Dutch trials of women allegedly linked to Islamic State (IS) that a victim is heard in court. "I burned inside when I saw her child. I lost two daughters because of people like her. She caused me a lot of pain," testified Z., one of the two victims in the case against a Hasna A., a 33-year old Dutch national from Hengelo, in Eastern Netherlands, who travelled in 2015 to Syria with her four-year-old son and married an IS fighter. The witness was assisted by an interpreter. For security reasons, she attended the hearings from behind a divider so that only the legal officers could see her.

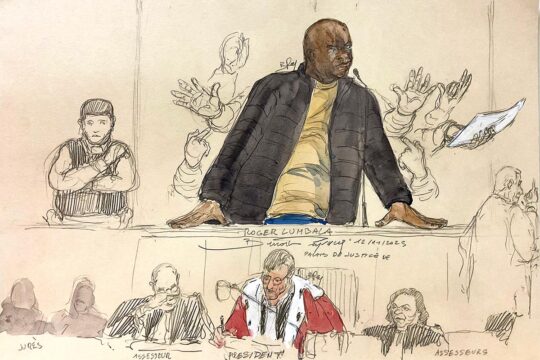

The evidence hearings last week in the case saw the interrogation of the defendant, the victims, the prosecution case and the defense case taking place in Schiphol Judicial Complex, close to Amsterdam airport. Hasna A. is one of twelve Dutch women who were repatriated with their 28 children in November 2022 from detention camps in Northern Syria, where they had been held following the fall of IS so-called ‘caliphate.’ She is being charged with slavery as a crime against humanity, relating to the enslavement of two Yazidi women (Z. and S.), and is also facing charges of membership of the terrorist organisation IS and for endangering her underaged son by bringing him to a war zone. The pre-trial phase started in February 2023. In the Dutch system this is the period where the investigative judge gathers evidence and testimonies and all parties compile their cases, which are then heard over just a couple of days of hearings. The two victims’ testimonies were taken during this period, together with a third Yazidi woman.

In court, the prosecutor asked for an 8-year prison sentence. It’s the heaviest sentence demanded for an IS woman so far. The victims' lawyers have also asked for a payment of 30.000 euros for Z. and 25.000 for S. for moral damage. The court has a victims' fund to pay in case the defendant is not able to.

Hasna A. denied treating the victims as slaves. Her defence lawyer claimed they lived in the same house but that her client did not give them orders or exercised any “property” – the term used for the crime of slavery – on them. The judgment will be delivered on December 11, 2024.

The “slave market”

The Yazidis are an ethnic and religious minority from Northern Iraq, as well as parts of Syria, Iran and Turkey. In 2014, IS invaded their homeland in Iraq, near the city of Sinjar. The Jihadist organisation saw the Yazidis as infidels. Hundreds of thousands fled to the mountains. Thousands of men were murdered, while women and children were taken to IS territory. Many women were forced into slavery and suffered sexual and gender-based crimes. To this day, around 2,600 Yazidis are still missing and around 130,000 live in refugee camps in northern Iraq. While the Iraqi government is trying to close down the camps, many feel like the Sinjar region is still too dangerous to go back to. In 2015, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights declared what happened to the Yazidis a genocide and in 2021 the Dutch government did the same.

“The Yezidi community has been totally disrupted by IS's attacks. Those who survived fled and were traumatised for the rest of their lives. That ruthless violence of IS is also the backdrop against which the slavery facts must be viewed,” stated prosecutor Mirjam Blom in court. Around 20 people were following the trial from the public gallery and two live streams in Dutch and Kurmanji were also available. The public prosecution explained that the IS openly referred to women as ‘sabaya’ (slaves), and that they sold them at the “slave market” and exploited them for sex and household work. “Some Yazidi women and girls were present at their own sale and were aware of the prices paid for them, which ranged from 200$ to 1,500$.”

Separated from her children

In August 2014, Z. and her children were abducted by IS combatants. They were then separated: Her then 10-year-old son was sent to an IS training camp, while her three daughters were exploited as slaves elsewhere. Z. ended up as a slave to an IS fighter in the Syrian city of Raqqa. She testified that she was locked up there, abused and forced to have sex by the man of the house, a friend of Hasna A.’s husband.

Blom said that “IS saw the Yezidis as objects, not people. And the accused's actions contributed to this”. Hasna A. is accused of using respectively Z. and S. as slaves between May and December 2015 and April and August 2016, when she lived with her husband and other IS fighters in Raqqa. The prosecutor alleges she knew the women were Yazidis and that they were held there against their will.

The victims had to spend many hours a day cleaning, washing the defendant’s clothes and cooking, and they were forced to pray five times a day, said the prosecutor. Z. also had to take care of the accused's little son, a child who is on the autistic spectrum, she said. “It is hard to imagine what it must have been like to look after someone else's child for hours a day while you yourself are separated from your children and do not know if you will ever see them again,” said the prosecutor.

“We constantly had fear in our hearts. Every day we could be sold, beaten or killed,” the prosecutor said, quoting Z.’s testimony. Hasna A. would treat her badly and she would threaten to report it to the men if she did not do something. According to the victim’s lawyer Brechtje Vossenberg, the defendant thought Yazidis were unbelievers. The most hurtful to the victim was the fact Hasna A. could have helped her get in touch with her children but she decided not to. “I begged her to let me call my son, but I wasn’t allowed to,” Z. testified.

Z. managed to escape in late 2015. She was later interrogated by the UN Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Islamic State (UNITAD), which closed its operation last September. She was never reunited with her children and some of them died.

Going to Syria to “build a new life”

The second Yazidi victim, identified as S., was held in another house with an IS fighter, where Hasna A. stayed for some time. The victim could not travel to the court for bureaucratic reasons so she followed the hearings via a video link. "We were slaves of IS to her and she also saw me as her slave," her lawyer read from S.'s statement while the defendant leaned to hold her head with her hands, looking down at the table in front of her.

When the three-judge panel asked Hasna A. whether she wanted to comment on the victim’s testimonies she said that it was terrible for her to listen to them. Her voice cracked and broke as she cried, but she did not acknowledge the crimes nor did she apologise during the three days of hearings. She told about her difficult upbringing. In 2014, she was in debt and was feeling depressed, she said. So she decided to practice her family’s religion, Islam. She started dressing accordingly and soon after she started thinking of moving to a more accepting place, to “build a new life”. In February 2015, she fled to Syria, a war zone. She did not think about the special needs of her son, who could not go to school or receive special care there. As a single mother she could not live on her own in the IS ‘caliphate’, so she was placed in a woman's house. It was to escape that situation that she married a Moroccan IS fighter she barely knew. She said he would neglect and threaten her and would not take good care of her children. By the time they separated just a few years later, she had three more children.

On the third day of hearings, defence lawyers André Seebregts and Mirjam Levy said that it was Hasna A.’s husband who placed her in the houses where the two Yazidi women lived. They pleaded that she was not in charge of the household and had no physical or psychological control over the victims. They pointed to inconsistencies in the victims’ statements and argued that the evidence did not meet the criteria for the crime of slavery.

Personal circumstances

If found guilty, Hasna A. could lose her Dutch nationality, as she also holds a Moroccan one, warned the defence. This could condemn her to live in the illegality. The defence also asked the judges to take into consideration the personal circumstances of Hasna A. It appeared that she had a problematic childhood and faced abuse. She was also diagnosed with a mild intellectual disability and a personality disorder.

According to the prosecutor, they took this into consideration but it was her lack of remorse that justified a 8-year sentence. “We have not heard her express regret for what she has done to others than herself and her family through her actions. And she certainly does not feel responsible for the contribution she has made to IS and to the terrible fate of the Yazidis.” The prosecutor added that she contributed to IS propaganda and ideology by posting photos of her children with IS symbols, carrying weapons on two occasions, and asking her father to join her in Syria – charges that the defence rejected. "She sees herself primarily as a victim and places herself next to the Yazidi victims as if IS women have had to go through the same things as the Yazidis,” concluded the prosecutor. “That is completely inappropriate and extremely hurtful to the real victims in this case.”

To base the requested sentence, the public prosecutor analysed previous cases held in Germany. The Netherlands is the second country after Germany to have trials for crimes against the Yazidis, under the principle of Universal Jurisdiction. German courts already issued two convictions for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes committed against this religious minority. On 19 September, a Swedish prosecutor also joined the accountability efforts when he charged a woman with crimes against humanity for what she allegedly did in Syria against Yazidi women and children.

The victims’ voice

“It was tough for me,” commented after the hearing Wahhab Hassoo, a Yazidi activist and co-founder of the NGO NL Helpt Yezidis. He said that the community, especially in Iraq, was disappointed by what was perceived as a low sentence in light of all the suffering their people and the victims have gone through. But he also thought it was a very important moment, a step forward in restoring the trust in international justice, at a low point after a decade of impunity. “The victims came to the podium to testify, and that’s what makes it so significant,” he said, hoping it will inspire more victims to come forward.

Public screenings were organised in three universities across Iraq’s Kurdistan, and around 200 people registered to watch the hearings there, said Hope Rikkelman, the director of Nuhanovic Foundation, which helped organise online access to the trial hearings as well as interpretation. Another dozen people followed the live stream in Kurmanji. According to Rikkelman, the Office of the prosecutor “went the extra mile to make sure Z. could travel to the Netherlands” from an undisclosed location. “I think that they're understanding that the concept of justice is not just about the verdict itself but about access to the case.”