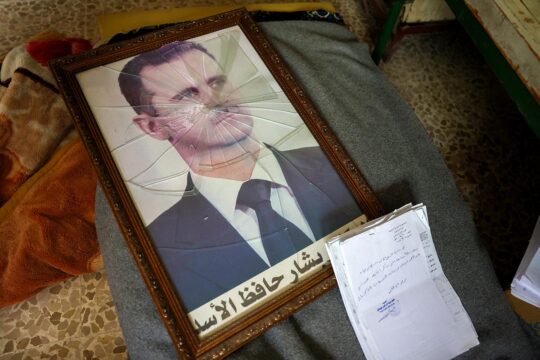

The unexpected fall of the Assad regime on December 8, 2024, in Syria has created a new situation in the country. One of the challenges ahead will be to determine what happened to the thousands of disappeared and dead left by the Assad dictatorship since the attempt to start an "Arab Spring" in 2011.

Syria is not the first country to be confronted to such challenge. Several countries, such as Argentina, Colombia, Guatemala or Peru (in Latin America), South Africa (in Africa), Bosnia-Herzegovina (in Europe) or Iraq (Middle East) have previously faced similar dilemmas: How to investigate what happened in a country with a recent past of violence? How far to go to bring to trial those responsible? Where are the bodies of the disappeared? Are there any disappeared still alive? The answers to these questions have been diverse.

Each country is different, and models applied in South Africa, the Balkans, Iraq or Cyprus cannot be transported automatically to Syria. On the other hand, there has not been a real exercise of "lessons learned" from diverse experiences at the global level, to draw some conclusions and not to repeat the mistakes made in other contexts. The arrival of foreign organizations and governments to advise the new authorities should be handled with care. The experiences of the Balkans, Afghanistan and Iraq, to cite only the most notorious examples, have not been entirely beneficial to these societies.

It's not CSI or Bones

Undoubtedly, the first mistake is not to sit down with the relatives of the disappeared and the organizations that can bring them together at the table where decisions are made, and to leave them out of the process. They are too often considered only as donors of saliva/blood samples for genetic analysis or simply as companions at meetings.

On the other hand, it is said locally and internationally that Syrian society is not prepared to carry out the forensic tasks involved in recovering and analyzing the thousands of bodies of the disappeared. But at the same time, there is no talks about the need to improve and train the local forensic medical system, so that Syrians themselves can make decisions, with foreign accompaniment.

From a technical point of view, there are also confusing messages. Genetics alone is not going to solve the identification problems. Taking samples from relatives of the disappeared and comparing them with samples from a skeleton is not enough. In massive cases, with thousands of victims, the so-called "false positives" can occur, that is, what seems like a match between bone and a family is not. This happens due to a genetic hazardous variation. Unfortunately, identifying a body doesn't work that way. It's not CSI or Bones. The comparison should be made in a complete and interdisciplinary way, appealing to the knowledge of other scientific disciplines such as Medicine, Dentistry, Anthropology, Imaging, and Genetics. This is what recommends the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the United Nations “Minnesota Protocol” on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Death (2016), a set of international guidelines for the investigation of suspicious deaths, particularly those in which the responsibility of a State is suspected.

What articulation between UN (and national) mechanisms?

The next problem, even more complex, is to know who the disappeared are. Generating identity hypotheses is critical in the identification process.

Who, When, Where, How and Why someone disappears are the first questions that we must ask ourselves before opening a grave. But it also implies having an investigative methodology with a deep knowledge of the conflict, the structures of the Syrian State, its modus operandi, where they took the detainees, how they disposed of the bodies, etc.

In the last forty years, a significant number of countries that had a violent recent past began to review that period using different mechanisms. Local trials, truth commissions, international courts, UN commissions of inquiry, ministries of missing persons, among others. In the case of Syria, it is a little different. During all those years access of investigative mechanisms into the country was prohibited, and there were no national bodies that did that task independently. The United Nations, in an unprecedented move, created in the last 13 years, three mechanisms to investigate in Syria: the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (created in 2011); the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism to assist in the investigation and prosecution of persons responsible for the most serious crimes under International Law committed in the Syrian Arab Republic since March 2011 (created in 2016); and the Independent Institution on Missing Persons in the Syrian Arab Republic (created in 2023). Although the latter has the mandate to investigate the disappeared, the articulation with the other two is still unclear.

If the new Syrian authorities decide to create a local mechanism (using the local justice system or a new one), it is also unclear what its mandate will be, who will be in charge and how it will articulate with the UN mechanisms. Another factor that adds to the complexity of the scenario is the number of civil society organizations that represent the relatives of the disappeared. How to achieve common agreements? What will be the participation of family members in decisions? How to prioritize cases?

Eight basic lessons

When it comes to forced disappearances at a mass scale, as it has been the case under Assad, the almost 40 years of investigations of serious human rights violations around the world have left us with some lessons that we should not underestimate at this stage in Syria:

- It is needed to create a single centralized mechanism, with independence and its own budget.

- Real participation of victims' relatives and their representatives in decision-making must be guaranteed.

- Design of a National Search Plan.

- Opening regional offices.

- Create an in-house forensic team, mixing international forensic specialists and Syrian forensic specialists, building at the same time a true local training process. A multidisciplinary team, with lawyers, historians, social anthropologists, investigative police, specialist in IT and Open-Source analysis.

- A nationwide information campaign for family members and communities about the Search Plan.

- Protection of burial sites as well as any type of information about the conflict.

- Construction of Forensic Data Banks, not only genetic.

Finally, it will be necessary to mention that this process will take years, if not decades. It cannot be solved with DNA alone, but it implies a long-term vision of the State.

Luis Fondebrider has been a forensic anthropologist for 40 years. He is a former director of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team and of the ICRC Forensic Unit. He worked in 60 countries investigating cases of human rights violations. He was a consultant for a number of international tribunals and UN investigative bodies, including the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and UNITAD in Iraq, as well as seven truth commissions around the world. Between 2018 and 2021, he was president of the Latin American Association of Forensic Anthropology.