JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

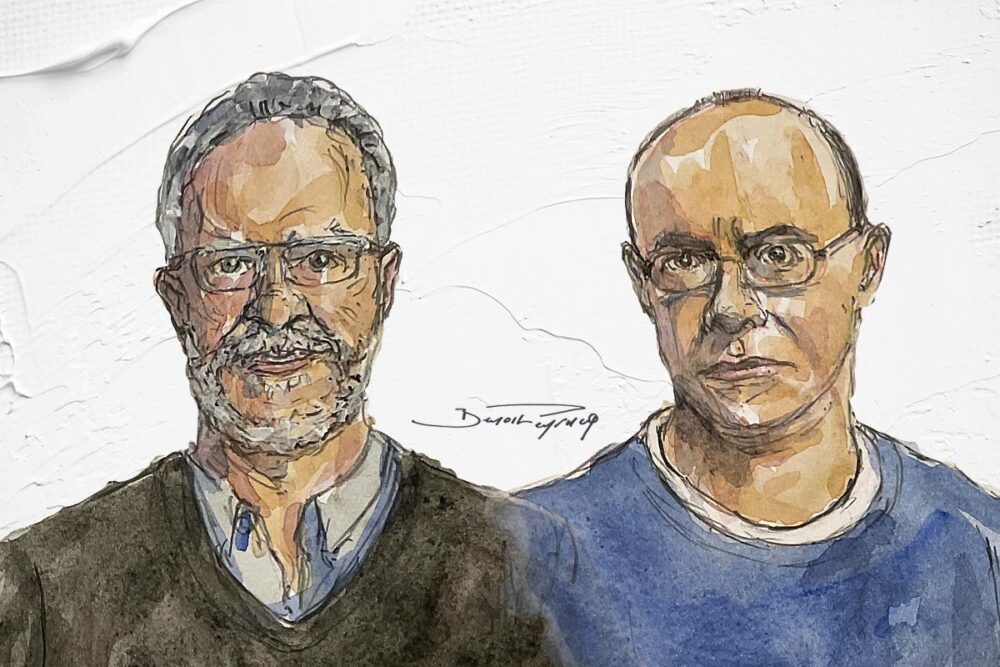

Azriel Bibliowicz et Ricardo Silva Romero

Writers

Two Colombian writers put language to horrors that could finally see justice this year in their country. The main characters of their novels are close relatives of victims – those for whom the crime continues long after it was committed. How powerful is fiction when reality defies the mind? How can language help when it has been so degraded by violence? What role can literature play in transitional justice? Azriel Bibliowicz and Ricardo Silva Romero take us out of the “hospital of words”.

After eight years of waiting, this year Colombia should finally see the first rulings issued by its transitional justice system. The Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) – the special tribunal born out of the 2016 peace agreement with the mission to shed light on the major crimes suffered by Colombians over a 50-yearlong armed conflict – has so far charged 169 people with war crimes, crimes against humanity or both.

Among them are 33 former members of the FARC guerrilla, including all of its former leadership, as those most responsible for the kidnapping of thousands of people. Also charged are 110 members of the military, including two former Army commanders, six other generals and a score of colonels, for their role in thousands of extrajudicial executions that Colombians know by the euphemism 'false positives'. Two crimes that are perhaps the most emblematic and infamous in a country accustomed to horror.

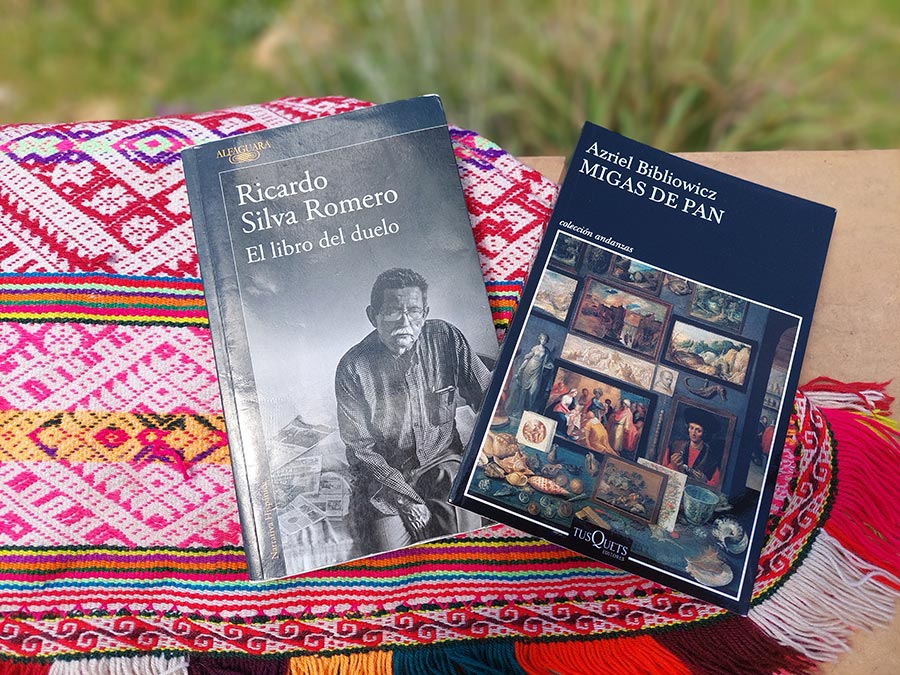

And also crimes that two Colombian writers put at the center of their fiction. In his novel Breadcrumbs (2013), Azriel Bibliowicz imagined the story of Josué, a Jewish clock seller who survives the Holocaust only to be kidnapped and plunged back into hell decades later, already settled in Colombia and still trying to heal the traumas of the world war. Meanwhile, in The Book of Mourning (2023), Ricardo Silva Romero focused on the real figure of Raúl Carvajal, a humble hauler who for years parked his van turned into a traveling museum in the heart of Bogotá, clamoring for justice for his son Raúl Antonio, who was an Army corporal killed for refusing to participate in the so-called false positives. (In an almost fictional twist, both books were edited by the same person, Carolina López Bernal, who is also Silva Romero's wife.)

Both novels reflect on these crimes with eloquence and empathy, putting precise words to pains that are almost unspeakable and that Colombians have grown accustomed to referring to in legal language. One describes false positives as "an enterprise of counting innocent and defenseless bodies that were executed hors combat to create the illusion that the war was being won," while the other calls kidnapping "a state of coma (...) with a score of three on the Glasgow scale, in which the patient doesn’t react to pain and only trusts a miracle, that something elusive will awaken him and the suspension will be broken."

Justice Info spoke with both about their novels, transitional justice and the importance of fiction in remembering these crimes.

JUSTICE INFO: Kidnapping and false positives are perhaps the two most visible crimes of the conflict in Colombia. Why did you choose to write about them?

AZRIEL BIBLIOWICZ: I did so because I had relatives who were kidnapped and because the Jewish community of which I am part was victim of this practice in a very dramatic way, to the point that a small community of about 3,000 people saw a quarter of its members opting to leave Colombia afterwards because of the trauma.

But most of all because a major problem of kidnapping was a fact that people normally did not take into account: almost everyone believed that the kidnapped person was he or she who’d been abducted. I realized that it was the whole family.

RICARDO SILVA ROMERO: My choice was very much motivated by the character of Don Raul, more than by the crime. Ever since he appeared in the Plaza de Bolivar and his story reached the press, it sent chills down my spine, just as I felt upon seeing Professor Gustavo Moncayo [who walked a thousand kilometers in chains and asking for the release of his military son, Pablo Emilio, kidnapped by FARC]. They have something that stirs a kind of ancestral memory, from the myths of the beginning of times: parents who traverse a country railing about the absence of their children. It was a tragedy because of the heartbreaking nature of a father burying his son, but also because he was a son who refused to participate in barbarous acts.

That image of him parking his museum truck every day in downtown Bogotá as if it were his office, telling the story of his son, which I even listened to a couple of times, having understood that this was the closest form of justice he would ever have, turned my stomach. When he died I wrote a farewell column, but it seemed clear to me that it didn't quite tell his story and that it had to be done in a way that was more emotionally understandable. We all feel uneasy about the numbers of massacres, but that doesn’t mean that we fully grasp their gravity. At the same time, but this was a coincidence, Don Raul's lawyer told me that his family wanted me to tell his story.

Both stories are told from the perspective of those who become full-time searchers of their loved ones. In Josué's case, his wife Leah and his doctor son Samuel wait for news that arrives sparsely, suffer imagining him suffering, and even give up their jobs to negotiate his release. While Don Raul and his family were able to bury Mono, he and his daughter Doris Patricia begin a quixotic quest to get the State to acknowledge that the security forces whose mission is to protect citizens killed him. Why did you focus not on the direct victims of the crime, but on their relatives who are also victims?

RSR: I’ve thought about it, but only after writing the novel. At the time it seemed very clear to me that this was the story of Don Raúl, as someone forced to be his son's evangelist. But as a result of the book I began to meet many people who work with victims and one day musician César López invited me to one of his 'resistance' concerts with victim-artists. I was hesitant to go because I didn't know what I would do there, because the person who has lived through that kind of grief in my house is my mother, who had two brothers killed. Since I was a child I've been aware and hurt by the murder of my uncles, one of them right on the Jimenez Avenue where Don Raul used to stand and another one in the Palace of Justice [in Bogota], but I did not feel it so directly. I ended up going and bumping into Helena Urán and Jineth Bedoya [emblematic victims of forced disappearance and sexual violence respectively] in the dressing room. And I felt absolutely comfortable talking to them, I felt like I was talking to my mom.

At that moment I realized that I am used to accompanying mourners, that I understand the language of trauma, the inability to escape the same story and always relive the same day. I felt that I do know how to talk about this, that I know how to accompany funerals and traumas. I understood that I have been writing from the point of view of those who remain, of those who survive barbarism and amid guilt, regret and pain are obliged to continue honoring the people who were killed.

People who had a kidnapped family member ended up glued to a phone, waiting for a call nobody knew when to expect. That's why the novel begins with that word, 'wait'.

AB: In the 1980s, the time period in which I set my novel, there were no cell phones and people who had a kidnapped family member ended up glued to a phone, waiting for a call nobody knew when to expect. That's why the novel begins with that word, 'wait'.

This waiting marks the whole novel because it has many meanings. On the one hand, it constitutes a display of power: if someone makes you wait in an anteroom in an office, that wait signals power. It’s an element that generates a distance, you have to wait for me to attend you. I discovered that the Nazis did that: they forced prisoners to wait for the commandant to arrive for hours in the harsh winter, in a display of that power. It also has a traumatic element because it generates a continuous present. A family ends up doing nothing else besides talking about waiting and concentrating on that continuous present, which is similar to the traumatic time of any person who is sick or who is sent to a gulag. It is another form of prison.

Ricardo, your novel chooses fiction to tell the story of a person who existed in real life, a father who "carries grief embedded in his liver until one day it metastasized" and seeks to prove to the world that "there were soldiers executed for being honorable". Why is Don Raul's journey towards truth so special?

RSR: There are several traits that make him a person you can feel you carry inside, almost an archetype. He is a father full of courage who wants to vindicate his son, who even bears his own name, who in the midst of that raging war travels around Colombia in a truck, almost proving that it is possible despite how dangerous it can be, and who is a worker. All of this in times when there is a clear social and global fascination with anti-heroes, from the 'Godfather' Vito Corleone to Walter White in Breaking Bad. I am interested in vindicating those who, without being caricatures and while still being complex, are not villains.

I was interested in the fact that he was a father in a world that tends to feel more represented by mothers. A father whom the mothers of false positives at first did not trust, but who ended up being one of them.

I also liked that his son was an honorable soldier. I always struggle in fiction and in my columns with how to convey nuance and make issues complex, which is why showing that the Army has had a lot of people who refused to commit heinous crimes was intriguing to me. In my upbringing and in my family, the Army was an agent of terror. I remember my mother's friends coming to the building where we lived when I was a 5-to-10-year-old child [between 1978 and 1982] to tell us that they’d been tortured in the Cavalry School right across the street. That’s why for me the Army was a pending task: to realize that if you look soldier by soldier you would discover that most of them were good, believed in what they were doing and were not the sordid corps of the Security Statute times [a 1978 law that extended the powers of the military and police under the mantle of domestic security and that enabled many human rights violations]. Here was someone who dreamt of being a soldier since he was young, who loved walking around the neighborhood in uniform, who felt that being a soldier brought dignity and honor to his family. And also because this was a family that, during Álvaro Uribe’ government [the period in which the bulk of the extrajudicial executions took place] and in a staunch pro-Uribe land like Montería, believed in the Army and ended up realizing that it was a fiction.

Finally, I was interested in the fact that he was a father in a world that tends to feel more represented by mothers, whether those of Soacha or those of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina. A father whom the mothers of false positives at first did not trust, but who ended up being one of them.

Azriel, two of your protagonists survive World War II – Josué a gulag in the Siberian tundra and his wife Leah Auschwitz –, only to be trapped half a century later in the horror of kidnapping in their host country. How is such trauma within trauma possible?

AB: I have always been very interested in the fact that Colombia is a sui generis country, full of contradictions. All writers know that contradictions are part of reality, but so many? For example, we live in an exquisite place – one of the most biodiverse in the world – but we demolish nature with enormous ease, as if we didn't care about it at all. Another example: in the 1980s we broke the world record for kidnappings. We ended up once again being extraordinary, but in a negative sense.

Colombia was the only country where a person who'd survived the Holocaust could be kidnapped and in fact I met a Jewish woman who arrived after the war and was later kidnapped by the ELN guerrilla. What happens here is often not possible in other places. Among other things, because to be kidnapped you didn't have to own a fortune and people were also abducted over insignificant amounts. It became one of the cross-cutting crimes in the country. That’s why I felt that the double captivity of both during World War II made sense: it was another historical event that it would never be possible to forget. No one who has been kidnapped can forget it, just like no one who endured a concentration camp can ever forget it.

Language is one of the great victims of war, because it distorts reality and our reality is speech. That is why within the 'cabinet of wonders' that Josué treasures there is a hospital of words where those words hurt by events may be cured.

Both of you underscore the peculiar language used by those committing or hiding these crimes. The guerrilla kidnappers speak with astonishing normality of a "doll" who "no longer protests" and ask relatives to "improve their offer" for the "merchandise". The military covering up false positives, or simply indolent to them, talk about how "he died as a national hero", "was killed in combat by a rebel" and that "there is no budget" to bury him. How important is language and the way violence distorts it?

RSR: It worries me above all when language is devalued by verbiage and lies, until it ceases to be useful. This can be seen very early on in the war: the impoverishment of language towards one full of clichés and bureaucratic jargon increasingly distances words from facts. In this context, institutions become machines and forget that citizens have stories, that we must listen to them and try to understand them. When a world is dehumanized, language is vain.

AB: After World War II, great writers such as Jean Améry and Paul Celan understood that language is one of the great victims of war, because it distorts reality and our reality is speech. I was interested in collecting that destroyed language because it is something that happens and of which people are often unaware. How is it possible, for example, that in Colombia we use the word 'vaccine' that cures us from diseases to talk about extortion? How did we turn around the meaning of a word that protects us into a plague?

That is why within the 'cabinet of wonders' that Josué treasures there is a hospital of words where those words hurt by events may be cured. And who are the doctors of words? It is the poets who find new ways to revitalize the word. It is almost an irony of history, as I say in my novel, that it was a Jewish poet like Celan who gave mouth-to-mouth breathing to German. Of course, a country with such a degraded conflict as Colombia has a long hospital of words.

Azriel, your novel delves into the uncertainty and the impossibility of joy for the relatives of a kidnapped person, how everyone is suspended in an "hourglass that robs our love drop by drop”. In its indictments against FARC, the JEP devotes significant space to the degrading treatment inflicted on captives, but also to the years of suffering endured by their families. Is this something that Colombians are sufficiently aware of?

AB: The family also suffers all sorts of traumas and horrible dilemmas. I tried to reflect them in the figure of the son, who was living with his family abroad but is forced to return to the country to rescue his father. On the one hand his wife feels that she’s been left alone taking care of their baby, but on the other hand he cannot leave his mother alone either and has to help her rescue his father. Or when kidnappers ask for outlandish amounts that families do not possess, or when families pay a ransom but are then told that in reality that was merely the initial payment, both terrible situations that happened in Colombia. These are terribly dramatic conflicts where no option is good.

In addition, kidnapping was a crime of an enormous complexity that we often forget: it became a business where many people were involved, like those who gave suggestions on who to kidnap, those who sold insurance policies against kidnapping, those who lent families the money for ransom payments in exchange for onerous deals over their possessions...

Sometimes I wonder if the monumental work that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission did has reached more than a thousand people or if it is limited to specialists. The basic question remains, how to popularize it more?

Ricardo, you document in great detail all the contradictions surrounding the death of Mono: the family is told that he was killed by the ELN in Tibú but also that it had been FARC in El Tarra, that he was shot by a sniper even though he had wounds at point blank range. There is also an accumulation of strange facts: obstacles for the Army to deliver the body to them, a combat that was not registered by any media, a fake psychologist who arrived at the wake… In its indictments over false positives, the JEP has placed great emphasis on the different modus operandi and strategies employed to disguise the killings of defenseless civilians as "fictitious operational results", from the staging of combats to the forgery of operational documents. Do you think Colombians are as aware of the twisted efforts to falsify reality as we are that these murders took place?

RSR: I've been to the JEP a couple of times, even to discuss this book, and it is very interesting because we always come back to the same topic that I often discuss with those who work with historical memory of the conflict. We always come back to the question, how do we get this to reach more people? Because sometimes you feel like you start to get to know everybody in that world and we all hear about the good work that is being done, but it stays amongst us. Sometimes I wonder if the monumental work that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission did has reached more than a thousand people or if it is limited to specialists. The basic question remains, how to popularize it more?

For example, it seems to me that the JEP figure of false positives has reached many sectors of society, although there are still opportunists like Congressman Miguel Polo Polo saying that there were not 6,402 but 1,200, which is nonsense and a passing scandal. I believe that the notion that this happened is already deeply rooted in Colombian society, even among those who reject the idea that there was an armed conflict here. We know that the war was degraded, that lines of barbarism and horror were crossed. That there were 6,402 Raul Carvajales, with families, with life projects and issues they needed to solve the following day.

Now, that there were strategies by groups within the Army to tangle the truth, disappear things and falsify reality, that is a next level requiring more interest and more time to grasp, perhaps because – again – people are not so attentive to nuances. In this world of herds, there are also others who assume that everyone is a thug and that there was an evil plan carried out by the entire Army, without really caring about how it was woven. That's why it was a dimension that interested me a lot.

In both novels, Colombian society is an anesthetized mass that has little concern for what happens to the main characters. Why do you think that, as the narrator of The Book of Mourning says, they "were alone in the task of justice because no one who was not up to his neck had time to find out about the war" and that, as the narrator of Breadcrumbs says, "this country with its thoughtlessness seems condemned to a farce [where] the kidnapped are and are not, and the war plows on but is negated"?

AB: I believe we are a country dedicated to forgetting because it’s very difficult to live in a country that has endured 80 years of violence. We have a capacity to erase what happens almost immediately and we also believe that it is enough, for example, to demolish the Palace of Justice building for us to no longer remember what happened there, or to change the name of the Palace of the Inquisition in Cartagena to Historical Museum to blur what really happened there (which is the subject of the novel I am working on now).

I think we have a logical need to forget, but those cultures that choose to erase their own history tend to make the same mistakes over and over again.

There is compassion burnout. It's not easy for a whole society to stop and think about pain and injustice, that its institutions have become entwined with war, violence and corruption. To think this all the time is paralyzing.

RSR: I think it's difficult for people to stop to attend to the drama of war for many reasons, including the fact that engaging in compassion – and this is a subject that interests me right now – can bring about illness to the person involved. There is compassion burnout. It's not easy for a whole society to stop and think about pain and injustice, that its institutions have become entwined with war, violence and corruption. To think this all the time is paralyzing. And it is also very hard to demand that a society forced, as Colombia is, to work from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., to be empathetic and take sides. It is understandable that people want governments that solve issues for them.

How do we get people to seek that time, to gain that clarity about what happened regardless of whether it was this one or that one, the right or the left, who committed a crime? That what matters is not the perpetrator but the seriousness of this happening to anyone. How do we get people back to the human agenda? More than indolent and asleep, these are societies without time, at a standstill and in constant vertigo. And war counts on that, on the fact that it is not easy to react from the human point of view and say 'hey, nobody can kill their father or their son'.

The first thing dictators and murderers want to ensure is oblivion, that we wipe the slate clean. But memory is like a cork: you try to sink it but sooner or later it ends up coming to the surface.

In Breadcrumbs, Leah – a survivor of Auschwitz traumatized by the death of her family in Treblinka and now dealing with the kidnapping of her husband – struggles with "memory being uncontrollable and stirring up the images of war and regurgitating them at any moment". Meanwhile, Josué dreams of an "almanac of ruptures" commemorating all the genocides in history and creates his own word to denote a place of memory since Spanish has none. Is there always a dance that goes back and forth between oblivion and memory?

AB: My novel plays with the role of memory and remembrance because they are fundamental themes and, well, also because the Jewish world has always been one concerned with memory. Besides, the first thing dictators and murderers want to ensure is oblivion, that we wipe the slate clean. But memory is like a cork: you try to sink it but sooner or later it ends up coming to the surface. And yes, it may come out somewhat distorted or different, but there it is, there it stays.

Of course we cannot remember everything because we would be like Funes the Memorious [the character in a story by Jorge Luis Borges], who suffers from remembering absolutely everything. But it is another thing to be forgetful as we Colombians often are. We tend to forget what we should not.

Sometimes reality seems to surpass fiction. Don Raul, the one in flesh and blood but also of course the one in your novel, died on June 12, 2021, the day after former President Juan Manuel Santos appeared before the Truth Commission and asked for forgiveness for the extrajudicial executions that took place while he was Defence Minister between 2006 (the year in which Mono was killed) and 2009. This coincidence is shocking and yet it went relatively unnoticed. Do you think that sometimes we do not take into account the importance of things that happen?

RSR: I think so. For a President of the Republic to have stood before a Truth Commission and asked for forgiveness in 1980, not to go too far back, would have been a turning point in the history of our country. But in this noise and atomization that exists today, the country is no longer seeing the same scenario or attending the same political arena. I don't know if it is better or worse, but it's certainly something else. Attention is so sparse and there are so many versions of events that each group has a different Colombia in mind and we end up having too many countries at once.

Moreover, it’s difficult for people to understand that the war is the most important problem in Colombia. I don't see in reality or in polls that people have that clarity.

A novel has a more poignant duration as it goes from hand to hand, little by little.

Ultimately, both characters reflect on the importance of stories to ensure that there is no impunity. Josué used to say that "it is with forgetfulness that murderers wash their hands" and Don Rául that "justice can only be served if the story was told". What role do you think literature plays in helping to minimize the chances of these crimes happening again, in a country still awaiting the first JEP rulings and still so divided over how best to end so much violence?

RSR: Fiction is the most effective tool to turn one's stomach. The effect of television is measured in millions, which becomes hundreds of thousands when we get to cinema and thousands when we get to literature. A very successful book here can reach 100,000 readers, but 10,000 or 30,000 people are already a good number to influence the reality of a country because their comments tend to radiate through word of mouth, starting with the people who are interested in the subject and reaching those who do not even know about it.

That reminds me of something that happened when the novel came out: Don Raúl's son-in-law appeared, called [daughter] Doris Patricia because he had just seen the book displayed in a store and their feeling was that what Don Raúl had wanted was for his story to be in the hands of most people. I like that idea of what is possible within justice because what institutions can achieve often falls short and is considered as unsatisfactory. A novel has a more poignant duration as it goes from hand to hand, little by little.

AB: I think literature humanizes conflicts and what I tried to do by telling the story from the perspective of these characters was just that. I come from a sociology background where conflicts are not personalized, but here you feel Leah's drama and Josué's drama. Literature generates empathy, you identify with the characters. And to that extent your experience is different.

Pablo de Greiff, Colombian jurist and former United Nations special rapporteur on truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-repetition – that is, victims' rights – insists that the purpose of transitional justice is to restore confidence among the people in a society and from them towards its institutions. Do you have hope that the path taken by Colombia with the 2016 peace agreement and transitional justice will achieve this?

AB: The fundamental point is that we should be able to live together within our differences and understand that this house belongs to all of us. That is what has been most difficult for us: we have such marked social differences, we have racism so embedded in our reality. This is the first time in our history that we have a black vice president [Francia Márquez], but still within our language the words 'black' or 'Indian' prevail as derogatory. There are common phrases like 'work like a nigger' or 'more brutish than an Indian' that reflect our lack of empathy about persons deemed as others. These are sick words.

RSR: In my opinion, this peace agreement was the most important event since the 1991 Constitution, which means that it would be one of the most important news in the history of Colombia. But one realizes that this is true for oneself and for a large group of people living in the country, but not to the entire country.

The problem is that we are living in a moment of regression, not only in Colombia but in the whole world, in which people who despise institutions and the State, who are more interested in saying what is wrong than in administering a country and strengthening its institutions, are coming to government. It is a moment in which one can very easily feel that the horizon has been blurred, but we must see, almost as if jumping from a close-up to a full shot, that the fact that the JEP exists, that we had the work of the Truth Commission and even that there is a struggle between those who defend the Havana peace deal [with FARC] and those who defend the 'total peace' policy [of current President Gustavo Petro] show that a culture – which did not exist here before – of therapy and dialogue about what has happened has not been reversed.

Azriel Bibliowicz was born in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1949. A sociologist, journalist and writer, he is a professor at the National University of Colombia and a founding member of its Film and Television School. In 1981 he received the Simón Bolívar National Journalism Award. He has published several essays and novels, including El rumor del astracán (1991), Sobre la faz del abismo (2002), Migas de pan (2013) and Del agua al disierto (2022).

Ricardo Silva Romero was born in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1975. He is a writer, journalist, screenwriter and film critic. In 2007, he was named among the best young writers in Latin America. Among his many books are Relato de navidad en la gran via (2001), Parece que va a llover (2005), Autogol ( 2009), El libro de la envidia (2014), Rio muerto (2020) and El libro del duelo (2023).