Persecution of “Nomads” in France did not begin with the Second World War. In 1912, parliamentarians of the Third Republic took discriminatory measures against the Roma, Manouches, Yenish, Sinti, Gitanos and Travellers. They passed a law grouping people “with the particular ethnic character of gypsies, bohemians, tziganes, gitanos” into the administrative category “Nomads”.

They were required to carry an anthropometric card, as the administration had to measure their height, length and width of their head, and the length of their right ear, among other things. A few years after the implementation of this law, the Interior Ministry set up a “central nomad service” to count more precisely the number of “nomads” circulating in metropolitan France.

On April 6, 1940, even before the Germans occupied France, a decree prohibited their movement. Prefects were free to choose between house arrest and internment in a camp. This decree marked the start of a daily headcount: every day, gendarmes came to check that the right number of people were in forced residence; every morning and evening, the internees in the camps were also counted.

But it didn’t stop there. The camp administration counted how many men and women were fit to work, how many men were old enough to do compulsory labour service (STO), how many people were over 60, how many children were under three, how many were minors, how many were suffering from tuberculosis, how many had escaped from the camps, how many were in hospital, and so on.

Officials also counted the objects they were using: how many plates, how many spoons, how many blankets, how many beds, how many caravans, and so on. The same was done with those under house arrest. These figures were then forwarded to town halls, prefectures, the Interior Ministry and the German occupation authorities. The act of counting had developed from a means of monitoring into a veritable weapon of persecution against “Nomads”.

The battle of statistics

Curiously, after the war no administration in France was able to say how many people had been persecuted as “Nomads”, how many had died, how many had been deported, how many camps there were in metropolitan France, or in which communes they had been put under house arrest - and so how many people could have obtained reparations. Astonishingly, most of the lists of persecuted “Nomads” were neither destroyed nor concealed. These fundamental tools for remembrance can be freely consulted in French archive centres.

Faced with this administrative amnesia, survivors of the persecution had no choice but to put forward their own figures, from the 1960s onwards. These figures reflected the suffering they had endured, but did not represent a truly exhaustive count of the victims. Many spoke of 30,000 internees in some 60 French camps and 15,000 deportees. The Inter-ministerial Commission for People of Nomadic Origin, on the other hand, claimed that most Gypsies had remained free in France during the war.

In the 1980s, hundreds of survivors and their children tried to obtain political internee status, i.e. recognition of the fact that they had been deprived of their freedom for discriminatory reasons and not for any crime. Faced with a flood of requests, survivors’ association pressure to recognize genocide, and pioneering work by amateur historians, the Secretary of State for Veterans and Victims of War, commissioned the Institut d’histoire du temps présent (IHTP) to write a report on Gypsies during the Second World War in France (1992).

This report published in 1994 argued that “the policy towards Gypsies followed by the Germans in France did not reflect a desire to exterminate them”, thus excluding persecution in France from the Nazi genocide of the Roma and Sinti. It concluded that only 3,000 Gypsies had been interned in France during the war. This figure of 3,000 internees was based mainly on incomplete data provided by the Inspection Générale des Camps in 1944.

This count also excluded those under house arrest, who were the great forgotten in the report. The consequences of this report for historical research were not good: the subject, which had taken so long to emerge as an object worthy of academic study, was now considered secondary. In 30 years, only one thesis was on Gypsies during the Second World War in France. The victims, who had not been interviewed by the report’s authors, had to wait until 2019 for a collection of testimonies allowing those that could to tell their story.

Since the 1990s, other figures have been put forward: in 2009, with publication of a book following a history thesis on the subject, the figure of 6,500 “nomad” internees was cited, while in 2018 at a Mémorial de la Shoah exhibition the figure of 6,700 internees was put forward.

Although these figures are undoubtedly closer to reality than the 3,000 internees in the 1994 report, they are still not based on a precise count of internees, and once again leave out those under house arrest. What is more, so long as we don’t know how many “Nomads” were living in France before the war, it is impossible to accurately measure the scale of persecution.

Naming the victims and remembrance

The official figures given in the 1990s had the effect of sidelining issues on the nature of the persecution and discrediting the victims. This benefited the administration, which was thus not obliged to account for any involvement it might have had. The descendants of the “Nomads”, who did not yet represent a sufficiently organized political force, did not have the means to respond to the narrative and propose a new count.

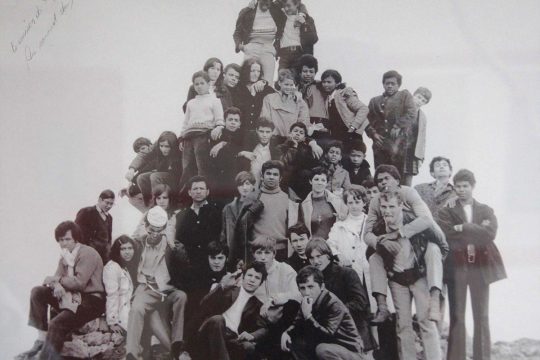

The “NOMadeS” project with a “wall of names of those interned and assigned to residence as ‘Nomads’ in France (1939-1946)” proposes to reconstitute, camp by camp, administrative department by department, the lists of Roma, Manouches, Sinti, Yenish, Gitanos and Travellers persecuted during the Second World War. The aim is not simply to count people, but to bring their names to life. It is conducted by the national Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), the Maison Méditerranéenne des Sciences de l’Homme (MMSH) and associations of internee descendants. It was put online last month.

The majority of “Nomad” descendants are still subject to a discriminatory administrative regime. In the early 1970s, the administrative category of “Nomad” was replaced by that of “Traveller”. The latter do not have the same rights as other French citizens, particularly in terms of housing and freedom of movement. Because of this continuity in French policy towards them, survivors of the persecution have often preferred not to tell their story. But this is changing: the “Wall of Names” was conceived with the children and grandchildren of “Nomads”, who are demanding the right to reparations and an end to the segregation that they continue to suffer.

Lise Foisneau is an anthropologist and research fellow at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS). In 2018, she defended a doctorate in anthropology at the University of Aix-Marseille on the political forms of a Romani collective in Provence, after several years’ itinerant fieldwork in a caravan. Since then, she has been researching the memory of the Second World War. She coordinates the NOMadeS database: “Wall of names of those interned and assigned to residence as “Nomads” in France (1939-1946)”