Just days before Donald Trump’s second inauguration as the president of the United States, the National Liberation Army (ELN), Colombia’s last “historic” leftist guerrilla group, launched an offensive in the region of Catatumbo, bordering Venezuela. Although the worst of the violence seems to have tapered off in February, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) audit and funding freeze -and the related social media conflicts between Trump and President of Colombia Gustavo Petro over tariffs and migrants deportation flights- have forced many in Colombia’s peacebuilding sector to rethink their strategies and expectations for U.S. engagement.

This USAID audit, led by the new U.S. Department for Government Efficiency (DOGE), is unlike any such effort under past administrations. The announcement of the 90-day freeze on funding, as USAID programs are being evaluated following opaque guidelines, is accompanied by highly inflammatory rhetoric by both President Trump and Elon Musk, who is leading DOGE. The significant layoffs in USAID offices around the world and the funding freeze have already seriously affected the U.S. delivery of humanitarian aid in Colombia and elsewhere.

Permanently closing USAID and increasing tariffs -which will have an impact on food prices thus on humanitarian aid costs-, as the Trump administration aims, could have disastrous effects, especially for the Accord’s ambitious System for Peace.

While no evidence has been released so far to suggest misuse of funds, and some programs are being reinstated as we write this piece, the Accord’s integration of truth, justice, and reparations will likely shape the audit’s outcome. More than financial oversight, this signals a broader shift in how Washington perceives Colombia’s post-conflict transition.

The Accord and U.S. diplomacy: from Trump to Biden

The first Trump administration’s approach to post-Accord Colombia prioritized counternarcotics efforts over peacebuilding and pressured authorities to resume aerial fumigation of coca crops despite concerns over its environmental and health effects. In 2017, the Trump administration threatened Colombia with decertification as a partner in the drug war, if coca cultivation persisted. While the U.S. did not outright oppose the Accord during this period, it showed little enthusiasm for its implementation, as it viewed it primarily through the security lens commonly associated with the drug war.

Despite calling for routine USAID audits of its own to ensure that funds designated for the implementation of the Accord were not used for either “reparations to victims or compensation to demobilized combatants” or “assistance to agricultural properties in Colombia that currently cultivate illegal substances”, the Biden administration took a broader approach to Colombia relations.

Specifically, its peacebuilding support emphasized rural development and environmental protection, two issues it recognized as fundamental to address the root causes of violence. The Biden administration also promoted voluntary crop substitution programs rather than forced eradication, in alignment with the Accord’s Ethnic Chapter goals. Additionally, the U.S. assistance emphasized political and social inclusion, particularly for Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities, positioning these efforts at the development-justice-security nexus.

This shift in approach meant greater U.S. support for Colombian institutions tasked with implementing the Accord. Now, institutions critical to the future of the transition, most notably the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) and the Unit for the Search of Persons Deemed Missing (UBPD), face operational uncertainty until the issue of the USAID funding freeze and the timeline for its implementation presented by the Trump administration is settled in front of the courts.

The Ethnic Chapter, the JEP, and the UBPD

The JEP is one of the most visible mechanisms of the Accord to have benefitted from USAID support. Among the three macro-cases supported by the U.S., Case 09 addresses crimes committed against ethnic and indigenous peoples, making special note of forced displacement, forced disappearance, and selective homicide.

The Accord’s Ethnic Chapter tied displacement to landmine use and prioritized roughly a dozen areas for humanitarian demining. Due to delays in implementation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reiterated these provisions in its 2022 Final Report. The JEP is currently working on legally grounding an alternative sanctions regime for FARC ex-combatants and security forces appearing before it, where legal benefits are contingent on their level of cooperation.

As for demining, it requires both labor and detailed information; precise data reduces the amount of work needed for safe clearance. Given the high prevalence of mines and accident reports in ethnic territories, the JEP is likely to factor this information into its alternative sanctions. Moreover, despite numerous hardships, FARC ex-combatants have formed a demining organization, further amplifying concerns about how USAID auditors will evaluate the JEP’s use of funds when considering these issues.

The UBPD also relies on USAID support and faces uncertainty. Determining the location of the missing-disappeared, like landmine clearance, is similarly labour intensive and reliant on precise information. FARC ex-combatants have established an organization to help locate remains and have been working directly with the UBPD. Several USAID programs have supported staff in developing technical skills in the peacebuilding sector, including methodologies sensitive to ethnic and gender diversity in implementing reparations under the 2011 Victims’ Law.

The UBPD’s national search plans -designed to locate the remains of the victims, involve local and ethnic authorities and promote participation by the victims’ families- reflect these earlier protocols. These plans also open up for the inclusion of FARC ex-combatants in the search, with a view towards alternative sanctions at the JEP, which is likely to cause confusion in USAID auditors.

Land reform, PDET, and security issues

Rural reform was at the heart of the Accord. Since stepping down as president, Juan Manuel Santos has been more vocal about the failed drug war and the need for cocaine regulation and decriminalization of rural communities and individual farmers who grow coca, the weakest links in the supply chain.

Despite the U.S. punitive stance on illicit crops, the Accord emphasized that the armed conflict will not end until the land inequality it created and reinforced is addressed. Under the Accord’s Development Programs with a Territorial Approach (PDET) and its pillar 8, USAID programming supported Colombian institutions in designing plans to help communities most affected by the violence to recover. Land titling and property rights, productive projects that substitute illicit crops and incorporate local economic actors, and infrastructure were conceived as fundamental transformative actions in this context.

As evidenced by the recent crisis in Catatumbo, post-conflict transformation is impossible without security guarantees. Despite not being subject to the same audit as USAID, it is worth noting that the U.S. Department of State contributed roughly $40 million in both 2022 and 2023 to the Colombian security forces. The nearly 50,000 people recently displaced in Catatumbo, together with the thousands forced from their homes by lower-intensity violence in Cauca, Chocó and Putumayo illustrate the challenges of ensuring short term humanitarian assistance. The USAID funding freeze and the potential increase in tariffs threaten the capacity of the Victims’ Unit to disburse immediate humanitarian aid to these internally displaced people and satisfy their basic necessities for food, which is usually purchased from U.S. farmers.

Addressing land inequality is not just about economic development, but helps prevent further cycles of violence. USAID played a critical role in developing the Comprehensive Security and Protection Program for Communities and Organizations in the Territories, the Accord’s main provision for the protection of human rights defenders and political leaders in rural regions, including those involved in advocating for illicit crop substitution in their communities. Given this, if USAID is to be drastically reduced or wholly terminated, as some have feared, it would run contrary to the counter-narcotics purposes of the U.S. policy in Colombia.

A critical juncture for Colombia’s peace process

The USAID funding freeze underscores a pivotal moment for Colombia’s peace process. Without sustained international support, key mechanisms like the JEP and UBPD face operational paralysis, jeopardizing efforts to deliver truth, justice, and reparations to victims. Moreover, reduced U.S. engagement could embolden armed groups, exacerbate violence in rural areas, and destabilize progress made since 2016.

While some USAID programs and funding are being gradually restored thanks to U.S. courts, it is necessary to develop strategies for long-term mitigation given the “America First” agenda of the second Trump administration. A more diversified funding base - including increased support from the European Union, Canada, and the United Nations Multi-donor Trust Fund for Peace in Colombia - could help bridge the financial gaps left by the U.S. withdrawal.

Strengthening local institutions and capacity-building efforts would allow Colombian institutions to assume greater control over peace initiatives, reducing dependency on foreign aid. Expanding public-private partnerships and NGO collaborations could also provide sustainable funding streams for development projects in conflict-prone areas. Lastly, multilateral cooperation through international organizations, such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and transitional justice networks, could ensure continued oversight and technical assistance for the Accord’s key mechanisms.

*This opinion piece was supported by funding from the Global Research Institute at the College of William & Mary through its Global Research Summer Fellows Program. The fieldwork stay in Colombia was organized by Adriana Rudling and Narayani Sritharan.

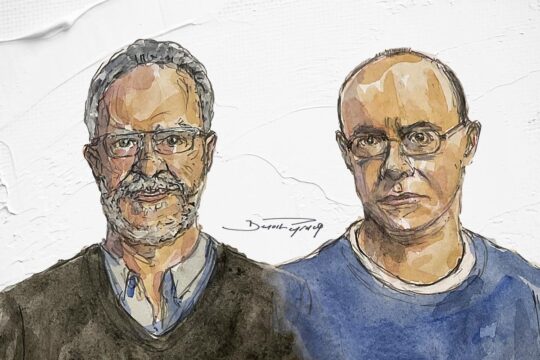

Braeden Garrett is a junior at the College of William and Mary in the U.S., studying International Relations and Finance. He is passionate about international justice and restorative peace.

Tomasina Pearman is a sophomore at the College of William and Mary in the U.S., studying Psychology and Government. She is a research assistant at the Global Research, working on global peace and peacebuilding issues at the intersection between psychology and international politics.

Clara Whitney is a senior at the College of William and Mary in the U.S., studying Film & Media along with Creative Writing. She is passionate about the cross-section between policy, politics, culture, and media.