“Since 2023 a genocide has been unfolding in the Republic of Sudan. The organization that goes by the name the Rapid Support Forces (“RSF”) and militias allied with it have been committing genocide against the Masalit group most notably in West Darfur”, states Sudan in its application to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), on March 4, 2025. Sudan adds that “persons among the Masalit were systematically targeted, on the basis of their ethnic identity and the colour of their skin”.

In the capital of West Darfur, El Geneina, Sudan alleges, “the rebel RSF militia laid complete siege to the city for 58 days [in April-June 2023]. People were burned alive. The rebel RSF militia engaged in extrajudicial killing, ethnic cleansing, forced displacement of civilians, rape, and burning of villages. The rebel RSF militia and allied militias have systematically murdered men and boys - including infants - on an ethnic basis. They have deliberately targeted women and girls from certain ethnic groups for rape and other forms of brutal sexual violence. They have targeted fleeing civilians, murdered innocent persons who were escaping conflict, and prevented remaining civilians from accessing lifesaving supplies”.

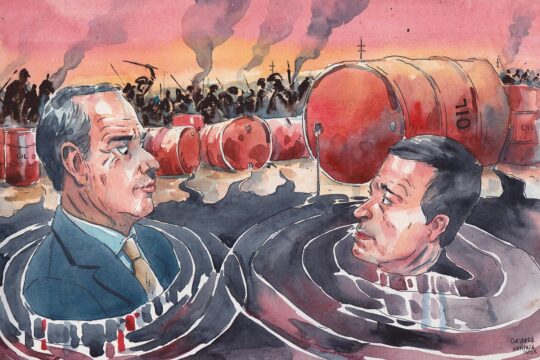

Next comes the target of the request: “The United Arab Emirates fuels the war and supports the militia that has committed the crime of genocide in West Darfur,” accuses Sudan. “The government of [the] United Arab Emirates has sent its own agents to the Republic of Sudan in order to lead the rebel RSF militia forces in carrying out the genocide. Much of the rebel RSF militia political communications and operations are managed in the United Arab Emirates. It has provided the rebel RSF militia forces with extensive financial support. It has recruited and instructed mercenaries in the thousands - from the Sahel, neighbouring countries, and as far away as from Colombia - whom it has sent to the Republic of the Sudan in order to assist the rebel RSF militia in perpetrating the genocide. It has sent and continues to send large shipments of arms, munitions, and military equipment, including fighter drones, to the rebel RSF militia forces which are carrying out its genocide. Experts of the Government of the United Arab Emirates have been training militia members to operate fighter drones”.

RSF militia “acting on behalf of the UAE government”

Regional analysts confirm much of what Sudan says. They point to work done by UN experts which shows that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is the main provider of the Rapid Support Forces. “Files were presented to the UN as proof about how Chad is used as a platform or a rear base for the United Arab Emirates to send weapons and equipment to the RSF in Sudan” says International Crisis Group analyst for Central Africa Charles Bouessel, adding that “the panel of experts of the UN and Sudan has established that this delivery was real”. Plus, he says, there is “plenty of open-source documentation”. “Without the Emiratis, the RSF would crumble in weeks,” he estimates.

In the complaint, Sudan says the UAE “is complicit in the genocide on the Masalit through its direction of and provision of extensive financial, political, and military support for the rebel RSF militia. The relationship of the rebel RSF militia to the United Arab Emirates government is so much one of dependence and control that it would be right, for legal purposes, to equate the rebel RSF militia with an organ of the United Arab Emirates government, or as acting on behalf of that government”.

UAE’s reservation: a seemingly insurmountable problem

However, Sudan’s attempt to get the matter addressed at the ICJ comes up against a seemingly insurmountable problem. Way back when the ICJ came into its current form and shortly after the Genocide Convention itself was first hatched into being, the court issued an advisory opinion in 1951 to all states to make clear whether a state could make a reservation to a treaty or not, when it signed up. For the Genocide Convention many states have made the reservation that they cannot be brought to the ICJ - nor can they bring other states to The Hague under the Convention. The UAE sits alongside many other states in the Middle East and - for example - China in having made that reservation.

The court clarified “what was, at that time, a deep uncertainty about whether treaty reservations were permissible or not” says Michael Becker of Trinity College Dublin. In its advisory opinion, the court said that “reservations are presumptively permitted, but only up to the point where they aren’t incompatible with the object and purpose of a treaty”, says Becker. On the social media site X, Sudanese UN envoy Ammar Mahmoud confirmed that Sudan’s submission to the ICJ “explicitly addressed this issue” [of the reservation] and argued that, “such a reservation carries no legal weight” because UAE’s “actions fundamentally contradict and undermine the core principles of the Genocide Convention”.

But Becker reiterates: “The validity of such reservations was tested by the court in 2006 in a case brought by the Democratic Republic of Congo against Rwanda”. And even though DRC “tried to argue that Rwanda's reservation to Article 9 [the one on jurisdiction] was not valid because it would violate the object and purpose of the Genocide Convention” that argument was rejected by the court, he says.

Alexandre Skander Galand, from Maastricht University agrees: “I don't think that the application by Sudan will pass the prima facie test for establishing jurisdiction”. And he finds it “puzzling” that if Sudan really wanted to challenge the court’s practice on reservations, they didn't go into that in more detail in the submission. “I was a bit surprised as to why they don't engage straightforwardly with that argument,” he says. “They don't say it clearly.”

Trying to get attention

The Genocide Convention is certainly one of the treaties in regular discussion at the ICJ that have made the headlines over the last few years. Since Gambia successfully argued that it had standing to bring Myanmar to the court, South Africa has done the same to Israel, Ukraine has argued about the Russian Federation accusations, and Nicaragua about Germany’s alleged complicity in genocide. The Genocide Convention is one of the elements that made the ICJ a popular space for states right now.

“We have lots of serious conflicts in the world involving mass atrocities”, acknowledges Becker. “And at some level, the Genocide Convention, even though it may not be a perfect fit for a lot of those situations because genocide is so difficult to establish, it remains the only option if you want to try to get a situation in front of the International Court of Justice”. “We increasingly see states interested in trying to litigate this question about complicity in genocide and wanting to find some way to take a harder line against states that are providing direct support to other actors, whether they're states or non-state actors that are engaged in conduct that might meet the definition of genocide,” he continues.

Skander agrees and points out that states are especially using the provisional measures phase of the court’s proceedings - which comes before the often very long-drawn-out discussions on the merits of a case - to try to get attention: “The court, in particular in this provisional order phase, has become an instrument for ordering states, other states, from ceasing their actions”. For example, Ukraine used the Genocide Convention for obtaining a provisional order against Russia in asking for a suspension of the military operation. “I’m not saying that Sudan will obtain that”, but that via the provisional measures hearings, “the court has received a high level of attention in the news and from society”.

A method to bring pressure on the UAE

And that may provide a clue to what could be the actual motivation here. Sudan is trying to publicise the UAE’s role in the conflict right now. “I think Sudan has understood that” says Skander. “In my view, it is using the publicity for hearing, where it could not have the same level of attention in other fora”.

Becker agrees that “this may be a sign of Sudan’s frustration with its efforts to raise these issues in other fora. And the fact that we are even talking about the claims means that they have succeeded to some extent. They may hope that this, in some way, is another method to bring some pressure to bear on the UAE or on their partners, to put pressure on other states to tell UAE, okay, enough is enough, things need to change in terms of how you are engaging in that conflict”.

The ICJ has long been an important space for states to resent their legal arguments. But now it has also become a major space for the public discourse on a conflict. “I think the court has become a place where you can wage your accusations, whether they be legally grounded, but at least politically informed, in a place where they will receive a significant amount of attention, even if - as in this case - the chances that it goes forward are very, very thin,” says Skander. “Given that they will most probably be discarded, we will never hear the merits. And this leaves us with a kind of suspicion of whether or not that was true, right? And so that will stay. We will always remember that the UAE is in Sudan’s view responsible for a genocide that is happening in its country, and this I find it extremely interesting. It is a new strategy”.

The bringing of yet another case the ICJ, by a party that has never before been in a contentious case at the court, seems to emphasise the bigger importance states are placing in proceedings before the ICJ.

“While in the past the states were more reserved because of the political or economic cost, we are seeing a world where the tensions are very high and perhaps the use of international law, of the International Court of Justice, is not seen as such as threatening for international relations. That raises a lot of questions in today’s world where, in particular from the Trump administration, there is considerable contesting of the international legal order. So, how to reconcile these two trends is quite puzzling,” says Skander.

![In its complaint to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), filed on March 5, 2025, Sudan states that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) “is complicit in the genocide on the Masalit through its direction of and provision of extensive financial, political, and military support for the rebel RSF militia [Rapid Support Forces, our picture].” Photo: © AFPTV Sudan has filed a genocide claim against the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Photo: Soldiers from the Rapid Support Forces in a combat vehicle are greeted by Sudanese in Khartoum.](https://www.justiceinfo.net/wp-content/uploads/Sudan_Rapid-Support-Forces-soldiers-Khartoum_@AFPTV-1000x667.jpg)