JUSTICE INFO: The UN’s Independent Institution on Missing Persons in the Syrian Arab Republic (IIMP) was created in 2023, when Bashar al-Assad was still in power in Syria and it was not possible to go there. But that changed unexpectedly after his fall, on December 8, 2024. How do you see the IIMP’s role now?

KARLA QUINTANA: Well, I think it’s more important than ever. As you know, this institution was created because of the fight of the families and civil society. And of course lots of member States supported this institution, which is the only one in the UN tailored to missing persons and the families of the missing. If you look at the Resolution that created us, it always had this idea that we would hopefully go to Syria – no-one thought it would happen so soon –, and even become a hybrid or national institution at some point. The reality before and after December 8 is totally different, not only for us but for everyone in Syria. Now we have the chance to eventually work in the field and to reach more Syrians than we could before. This opens a huge window, but also lots of challenges. We have a mission in Syria now, and we are planning to have monthly missions to work on different issues. We are starting to investigate missing children, but that’s only one of many topics we are working on. What we would like to have is an office in [the capital city] Damascus, and we have asked for that.

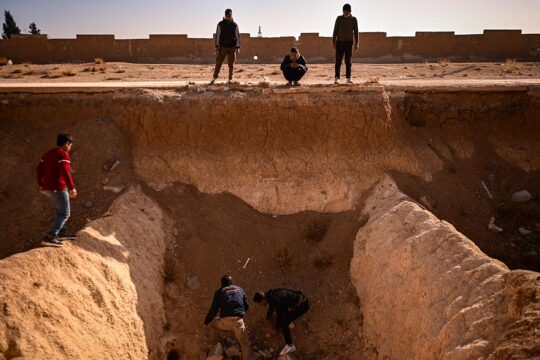

Now that Syrians are looking on their own for the missing – we remember the images of people digging for bodies in Sednaya prison -- and exiled Syrians can go back, do you think the IIMP still serves a purpose?

I think Syrians need to do it themselves. I was myself the head of a national institution [in Mexico] for the search of the missing and that’s why I’m truly convinced it has to be nationally led. But no-one can do this alone. We are talking about at least 130,000 people missing, and this is only an estimate based on the work of civil society. The Syrian authorities are thinking of creating a national authority to search for the missing, and I think they’re right.

However, I do believe that the IIMP should have an important role in that. We can bring expertise, we can bring comparative experience from many parts of the world – from the Balkans, from Argentina, Guatemala, Mexico, and Cyprus. So we have all that experience in searching for the missing, both alive and dead, that we can bring to Syrians to help them build their own mechanism. I believe we have to help them build their own institution, and help them not only with knowledge but also the human, technical and financial resources. We are willing to do that, and I think we have a very important role to play in the coming years, because it’s going to take years.

We have to make the families and civil society part of this process. We have experience in doing that all over the world. First, the families of the missing are the ones who have more information than anyone. And if you are the government or an international institution and they don’t trust you, they are not going to give you that information. So working with the families is not only an ethical issue, it’s a central part of the search. And to build trust, they have to see you working in the field, not just giving speeches, sending Tweets. That’s why it is so important for us to have an office in Damascus.

What are your budget and resources?

The regular UN budget approved last December [just before the regime fell] was $11,057,500 for 2025, and we currently have 28 staff. We were supposed to have 47. We were starting to hire new staff when I got here in January, but as you know there were cuts in the UN, a freeze. So it’s a critical moment for the world in terms of resources, and it’s impacting us. But the good news is that we were approved [by the UN] a Trust Fund a few weeks ago [for voluntary contributions from member States]. We have already been offered at least $1.2 million from Germany and Luxembourg, and we are hoping to get more funding from other countries.

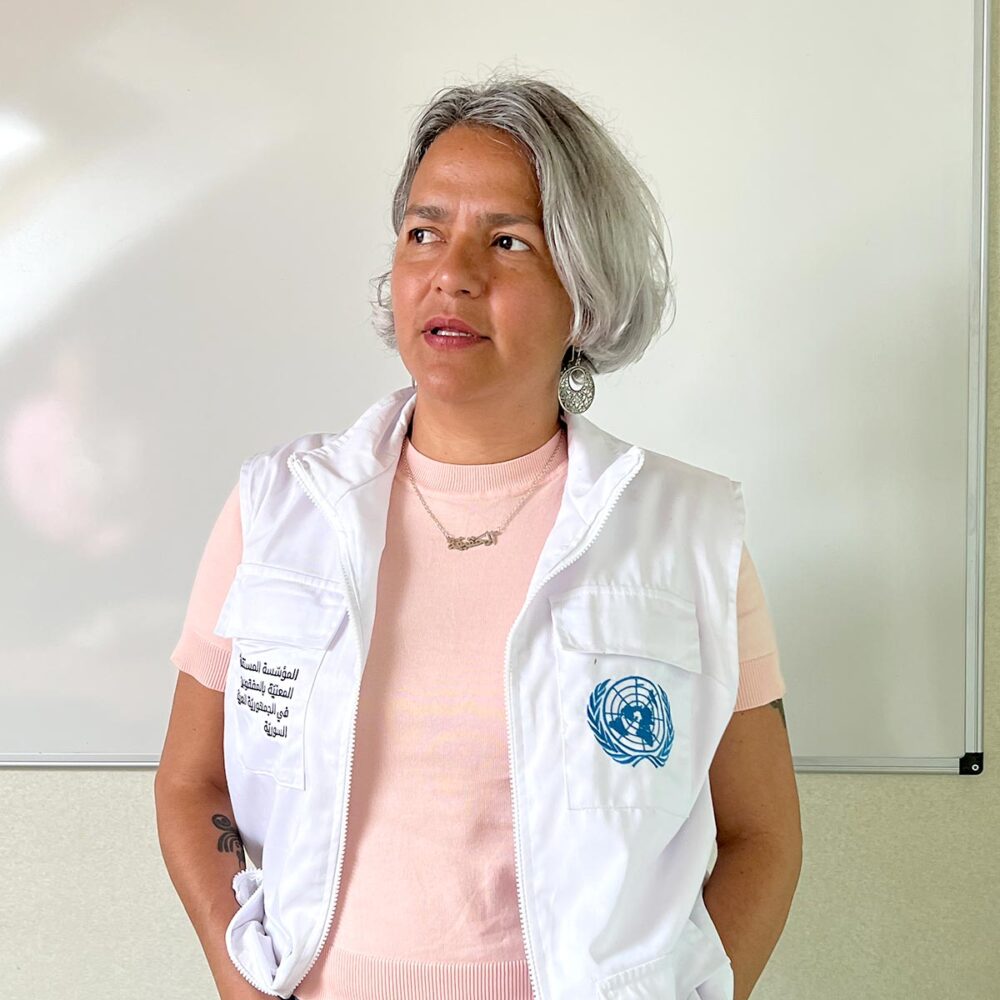

You made a first visit to Syria in February. How important was that?

It was of paramount importance. It was unbelievable, I think, for many of us. We went to Beirut, and we drove from Beirut to Damascus. There you see a sign “Welcome to Syria” that would have been unbelievable a month and a half ago. It was very important for us and everybody that the independent institution go and see things directly.

Families and civil society from the diaspora have done a fantastic job, not only in documenting what was going on in Syria but also lobbying to create us. But now we have another challenge, which is to work with the families that didn’t leave Syria and have so many people missing. Literally everyone that talked to us knew someone who is missing. When we took a cab, the drivers started to talk about nieces, nephews, brother, father, someone close to the family who was missing. When we went to a restaurant, the waiters would come and talk to us. I went to the restroom in the restaurant, and someone came to talk to me.

They knew who you were?

We had this vest, with “Independent Institution on Missing Persons in the Syrian Arab Republic” marked in Arabic. I asked everyone in the team to wear it everywhere, because I know from experience in Mexico that anywhere you go there’s going to be people that come and talk to you if they see you are looking for the missing.

What kind of relationship do you have with the transitional authorities?

I have to underscore first that we have a relationship with the authorities. We weren’t able to say that before December 8, and I think that’s very important. I have met with Foreign Minister Asaad Shaibani twice, first when we went to Damascus and then in Brussels. He is the minister in charge of talking to all the international institutions, and he is a window to talk to any other authorities. I tried to explain to him who we are, what we can do, what we can offer. I made it very clear that for us, in terms of the missing, it’s very important that it’s Syrian-led, and internationally supported.

Did you get the authorization to set up an office in Damascus?

Shaibani asked the day I met him for us to present a programme of what we think we can offer. When I met him the second time in Brussels I gave him a very broad programme. We insisted on having an office. What I was told was they were waiting for a new government to be appointed, and it was appointed only recently. What we agreed is that I would go back after the government was appointed.

There are many UN member States that are willing to help in the search for the missing. I was going to New York after I met him, and I said “can I tell them that we are going to work together”, and he said “yes”. So that’s a very good sign. The specifics we don’t know yet, but I think the political will is there.

Concretely, how are you working with Syrian civil society and NGOs?

We meet with them consistently here in Geneva, almost on a daily basis. We work with them, we consult them, we go to meetings with them all over Europe. Only a few days ago, one of our colleagues was in Berlin, a few weeks ago there was a missing migrants conference here, and so on. The mission that is taking place in Damascus is also meeting with civil society. We try to have missions with 2-5 people, and hopefully we will have an office there with many more people.

As you said, there are many people in Syria who don’t know you…

We have to be there. When we were there in February, for instance, we went to this place called Darayya which is in the outskirts of Damascus and it was destroyed in the war, there was bombing there. We met with a group of women, and of course they didn’t know us. They didn’t even know there were other civil society organizations that were looking for the missing, let alone that we exist. So there’s huge work to be done, not only for us but everyone in Syria, to know exactly who we are looking for. I think the number of people missing in Syria is much more than is documented, because people normally are afraid of talking to anyone. There were people who never, ever talked about their missing loved one before we went there.

There are a plethora of organizations working on Syria. How are you working with other international and UN organizations, especially the Syria “Mechanism”, IIIM?

Although there is a plethora of institutions working in Syria, there are only three in the UN that are tailored specifically to Syria: the commission of inquiry, which was created very early; the IIIM; and us. The commission of inquiry and the IIIM are accountability, and we are humanitarian. We do work together, we have weekly meetings, to share the information we can share, bearing in mind their accountability role and our humanitarian role. The IIIM and we are both thinking of having an office in Syria, but not sharing it. I don’t think that would send the right message to victims, because there are people who might be willing to give information if they can do so anonymously and only for search purposes, but not necessarily for a tribunal.

Your mandate is not only to clarify the fate and whereabouts of all missing persons in Syria, but also provide “adequate support” to victims. How will you do this?

I would add another question: who is to decide what adequate support is? Because I think if you ask someone in Darayya, in the northeast or northwest of Syria, in Germany, the US or Canada, the answer is going to be different. What I know is that the first form of support or participation is for families to be part of the process. That could mean, for example, that if we are allowed to open a mass grave, they should be there if they want to. They need to know how the forensic process works. And then there are so many other questions about psychological support. We are working on that with member States, especially those that have a larger number of Syrians in their countries. We are not going to do it by ourselves, we are going to help create a support network within the different countries and of course in Syria. It’s titanic, but we are moving. It’s a window of opportunity.