The International Criminal Court (ICC) must broaden its investigation into the 2010-2011 post-election violence in Côte d’Ivoire to include violations committed by loyalists of President Alassane Ouattara, Human Rights Watch said in a report released Tuesday.

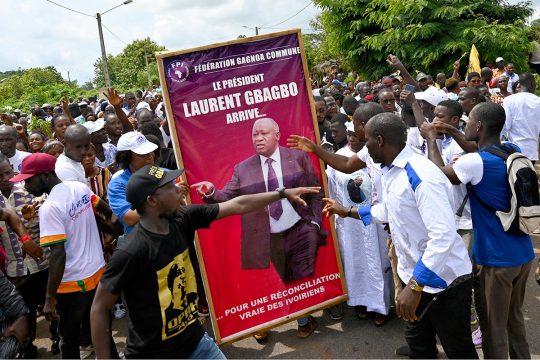

Since 2011, ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda has been probing a conflict that erupted after former president Laurent Gbagbo refused to concede defeat to Ouattara in a vote the year before. However only Gbagbo and figures loyal to him have been charged so far by the ICC for crimes committed in post-election violence that left at least 3,000 people dead.

The HRW report also says that to maximize the impact of its work, ICC court officials need to engage a broader set of victims and local communities.

Elizabeth Evenson is senior international justice counsel at Human Rights Watch. She spoke to JusticeInfo.Net about the report.

JusticeInfo.Net: The report says that there have been “missteps” in the ICC approach to justice in Côte d’Ivoire. Can you tell us briefly what these “missteps” are?

Elizabeth Evenson: First, the Office of the Prosecutor, even though it said from the beginning that it would look at all sides to the post-election crisis and abuses were committed by all sides in that 2010/ 2011 conflict, they decided to focus first on investigating alleged crimes by forces associated with the former president, Laurent Gbagbo. There is a certain logic to that decision. They told us they were able to assess evidence in Abidjan, Gbagbo was already in detention, so there was an opportunity to have him surrendered, and it would have increased the logistical challenges if they had done other investigations at that time. But unfortunately that initial decision to focus on pro-Gbagbo forces has now persisted for several years and it’s meant that the only cases that are open before the ICC right now relate to one side of the conflict. So that was really the first misstep and the result has been predictable. Opinion about the ICC has become polarized, people feel that the ICC is biased in its work since it has only focused on one side, and most fundamentally it has meant that victims of abuses committed on the other side, those affiliated with the current president Alassane Ouattara, have not had access to justice before the ICC.

JusticeInfo.Net: And you say this has limited the impact for victims?

EE: What our report then looks at is what did this mean, because the Court has other important responsibilities, and that’s at the heart of this report. What the Court does in The Hague has to be accessible, it has to be meaningful to victims and communities wherever the Court is working as in Côte d’Ivoire. And there are other Court officials within its Registry that have very important responsibilities to provide information to the public and to provide specific information to victims about their rights. And here’s where the second misstep came in. Essentially, those other Court actors used the Prosecution’s narrow approach as a rationale for having their own limited approach.

JusticeInfo.Net: So you are saying the root of the problem is the fact that the prosecutions have been one-sided, and this has been exacerbated by lack of resources?

EE: I think that’s a very fair way to put it. It’s possible that the Registry could have made some different decisions, but they ran up against a pretty hard limit in not being able to have somebody to do Outreach on the ground (until October 2014) and that then forced a narrowing in their outreach. It has looked like a very selective approach by the prosecution, and having narrowly focused outreach programmes has compounded that sense of selectivity and just hasn’t given the Court what it needs to engage with this very polarized opinion about the Court, let alone shift that polarized opinion.

JusticeInfo.Net: Relations between the government of Alassane Ouattara and the ICC haven’t been easy, for example the government refused to hand Simone Gbagbo over to the ICC. Has this played a part?

EE: That’s right, but in our research that didn’t come up as a significant limitation on what the Court could do, say, in outreach. They were able to open an office in Abidjan. No-one suggested to me that they wouldn’t have been able, had they had the resources, to have an outreach officer on the ground. That relationship between the government and the ICC has not, as you say, been a smooth one, and the refusal to surrender Simone Gbagbo really stands out. But it didn’t come up in our research that that could explain the narrow approach to outreach and to a lesser extent victim participation. It’s really more about the resources they had, and the choices they made with those resources.

JusticeInfo.Net: National trials in Côte d’Ivoire have also focused on trying the pro-Gbagbo side only, although there seems to have been a change with a first case against pro-Ouattara suspects. Do you think this could make it easier for the ICC also to go after the other side?

EE: As you say, there has been a change. That’s very positive. But the national investigations are still under way. They haven’t yet resulted in trials. It’s certainly important that they do. But it seems to us that there’s still going to be plenty of space and plenty of need as well for the ICC to do what its Prosecutor has now said it would do, which is to conduct those other investigations. I must say, I don’t have any analysis on whether change in the national posture is going to make it easier for the ICC, because the ICC Prosecutor didn’t say to us that cooperation was the reason that they had focused initially on pro-Gbagbo forces. And cooperation is a problem that the ICC prosecutor is going to confront in any situation. We’ve seen that of course in the Kenya situation, which has probably been one of the more dramatic displays of that. But that’s a standing problem and it can’t control the prosecutorial strategy. The strategy has to be driven by what is the contribution that the ICC should be making to justice, and then how can the rest of the Court complement that to make sure that those proceedings are accessible to people in the country.

JusticeInfo.Net: You say that the report looks at Côte d’Ivoire as a case study but there are also lessons for the ICC in other countries. So what lessons for which countries?

EE: We’ve seen in the Democratic Republic of Congo there was a similar problem, very early on in the ICC’s history of only looking at one side and then a delay before looking at the other side in the Ituri conflict. It created the same perception problems that we’ve seen in Côte d’Ivoire. In Libya currently, the only open cases are the cases against ex- Gaddafi officials. Meanwhile there were crimes committed by militias during the Revolution and there are new and very serious and significant crimes going on in Libya. So, if the top lesson is that there has to be more of a focus by Court officials on what does it take to deliver meaningful, accessible justice for victims and affected communities, there are then specific lessons, one for the Office of the Prosecutor, to have a stronger approach at the outset of investigations, a stronger sense of which cases, following investigations, they will need to do for the ICC really to be seen to be doing its job.