ABIDJAN, 21 July 2015 (IRIN) - Five years after Côte d’Ivoire’s disputed presidential election threw the country into turmoil and left more than 3,000 dead, its people are set to go to the polls again. Could we see similar unrest this October or will the West African nation turn the page and move forward?

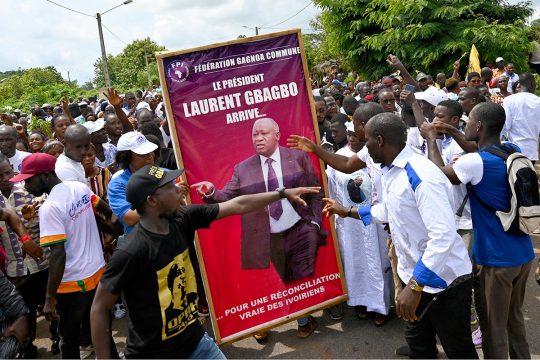

Former president Laurent Gbagbo, who refused to quit when declared the loser of the 2010 election to Alassane Ouattara, is now in The Hague charged by the International Criminal Court (ICC) with crimes against humanity.

Côte d’Ivoire’s economy is booming and Ouattara has gained popularity. Gbagbo – seen as the only viable challenger – is unable to run.

There is every chance the vote will pass off peacefully, but this doesn’t mean all has been forgiven between the two camps.

See: Paving the way for justice in Côte d’Ivoire

The Dialogue, Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was supposed to forge unity and resolve long-standing political and ethnic divisions, is one of the country’s most unpopular institutions and Ouattara is accused by some of presiding over “victor’s justice.”

See: Worries over looming Ivoirian polls

With less than three months to go until the election, human rights experts and political analysts identify three key areas of concern:

Political prisoners

The detention of as many as 700 political prisoners remains a deeply divisive issue. Supporters of Gbagbo demand their release, buthis opponents say justice must be served.

“The current government is not willing to create the conditions for a peaceful society,” Dahi Nestor, president of the pro-Gbagbo opposition’s National Youth Coalition for Change, told IRIN. “It continues to keep innocent people in prison. This is an attack on democracy. A normal country cannot go to elections with hundreds of political prisoners in its jails.”

Ouattara and his government maintain that those imprisoned were not arrested because of their political affiliation but because they broke the law. “We want reconciliation,” the president said, “but we do not want a lawless country.”

Selective justice?

The sentencing in March of former first lady Simone Gbagbo and two co-accused to 20 years in prison for “undermining state security” - and of some 65 others supporters of her husband to shorter terms -was confirmation to opponents of Ouattara of a lop-sided justice process.

Watch: Côte d’Ivoire: In Search of Stability

Both sides were accused of civilian massacres in 2010-2011 and yet only those allied to the former president have been convicted of any crimes.

“Unfortunately, we will not have this equal justice before the next election, because the more we advance towards this deadline, the more that resources and attention are diverted to the polls,” Barthélémy Touré, a political analyst in Abidjan, told IRIN.

Too scared to return

Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution says no citizen can be forced into exile, but nearly 50,000 Ivoirians, including political and military exiles who fled to Liberia, Ghana, Togo and other countries during the 2010-2011 crisis, still cannot - or will not - return home, according to the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR.

Despite pleas from Ouattara for them to come back, many say they fear ending up in jail or being persecuted if they do.

Franck Kouakou Tanoh, a member of the Young Patriots – a pro-Gbagbo youth movement – has been exiled in Ghana since April 2011. “It is not the urge to return that we lack,” he told IRIN by phone, adding that he just don’t believe assurances that they will be treated fairly.

The opposition is also demanding the return of its leaders, including Gbagbo and former head of the Young Patriots Charles Blé Goudé, who is also awaiting trial by the ICC. The opposition says it plans to boycott the October elections if its demands aren’t met.

Bisa Williams, US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, who visited Côte d’Ivoire earlier this month to discuss the electoral preparations, urged all parties to remain involved in the process despite their differences.

“Certainly, Ivoirians have had a difficult time these last four years,” she said. “But I have a feeling this negative energy is gone and that there will no longer be this big divide between people. It is true that there will always be disputes, but hopefully not any that will destroy the country.”

Peter Kouame Adjoumani, president of the Ivoirian League of Human Rights, noted some progress but still had big concerns.

“There are important issues that have not been resolved and could explode the situation,” he told IRIN.