“I believe that Member States, and this Council, can intervene effectively to prevent the repetition of past horrors,” United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein told the UN Security Council in November at the start of a debate on Burundi. His allusion was to the genocide perpetrated against Tutsis in 1994 in Rwanda, Burundi’s neighbour.

The UN Secretary General’s Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, Adama Dieng, issued a similar warning. "Given the clear information we have about the gravity of the situation, we will not be able to claim, if a full scale conflict erupts, that ‘we didn’t know’,” he said. “The international community has a responsibility to protect Burundians and to prevent the commission of atrocity crimes."

Even outside the UN system, governments and civil society organizations had been, and are still sounding the alarm.

But almost nothing has changed since. The inertia and inaction of the international community continues to strengthen the determination of those perpetrating violence in Burundi. And a senior UN official recently admitted that if the “worst” happened in this small African country, the UN would not have the means to react adequately.

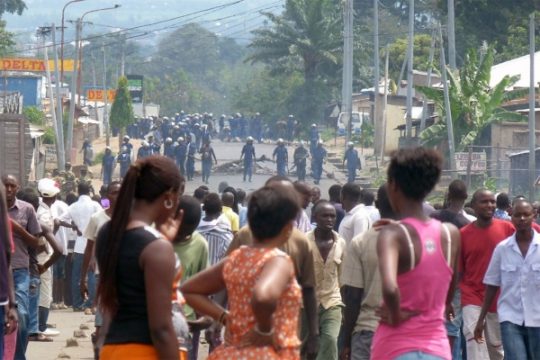

Burundi has been in deep crisis since the end of April 2015 when the party of President Pierre Nkurunziza backed him to run for a controversial third term in office. The third term was denounced inside and outside Burundi as being unconstitutional. His re-election in July has not stopped the country’s civil society and opposition from demanding his departure.

“All talk and no action”

So, after numerous warnings from the international community, all eyes were turned on New York last November. But UN Resolution 2248 of November 12, 2015 merely urged the government and other parties in Burundi to reject all forms of violence and refrain from “any action that would threaten peace and stability in the country”. It also says the authorities in Bujumbura must “respect, protect and guarantee all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all”, in line with the country’s international obligations. “There’s nothing new! It’s all talk and no action,” was the bitter comment of a Burundian MP who is a member of the Legislative Assembly of the East African Community (EAC), a sub-regional organization comprising Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda.

After this minimal resolution in New York, hopes turned to the 565th meeting of the African Union’s Peace and Security Council (PSC). In a much-heralded decision, the PSC on December 17 authorized “the deployment of an African Prevention and Protection Mission in Burundi (MAPROBU), for an initial period of six months renewable” and urged the Burundian government “to confirm, within 96 hours following the adoption of this communiqué, its acceptance of the deployment of MAPROBU and to cooperate fully with the Mission”. The PSC expressed its “determination to take all appropriate measures against any party or actor, whomsoever, who would impede the implementation of the present decision.”

The African Union move came a week after a December 11 attack on three military camps in and outside Bujumbura, the worst clashes in Burundi since a failed coup in May 2015. The clashes and the clampdown that followed officially left 87 dead but NGOs and the UN put the death toll higher.

Burundian civil society, which has become a key player, hailed the African Union decision but without excessive enthusiasm. “We welcome the AU Peace and Security Council decision on the deployment of MAPROBU,” said Pacifique Ninahazwe, a prominent activist now in exile. “But they will need to be as diligent as possible. Taking a decision is one thing, implementing it is another.”

Which countries are ready to provide troops? Who will fund a 5,000-strong African force? These are some of the questions that help to explain the scepticism of the Burundian civil society spokesman.

Nkurunziza digs in

But there is worse. As the lack of firmness of a divided international community has become more apparent, the authorities in Bujumbura have become more intransigent. “Burundi will not authorize the deployment on its soil of an African Union mission,” declared Nkurunziza spokesman Jean-Claude Karerwa, adding that if such a force went ahead it would be considered as “an invading and occupying force”. Government spokesman Philippe Nzobonariba issued a similar response. “If the African Union sends troops without Bujumbura’s consent, it will be considered an attack,” he said.

President Nkurunziza used an open press conference on December 29 to hammer the message home, invoking national sovereignty. “Everyone must respect Burundi’s borders,” he said in the national language Kirundi. “If the (AU) troops come (…), they will have attacked Burundi, and every Burundian should rise up and fight them. The country will be under attack, and we will fight them.”

According to the African Union’s PSC, one of MAPROBU’s main tasks of would be to help create conducive conditions for a resumption of all-party Burundian negotiations which stopped in July after the government pulled out. They were supposed to resume in Arusha, northern Tanzania, on January 6 but the government reiterated its firm refusal to talk to representatives of the National Council for Respect of the Arusha Accord and Return to Rule of Law in Burundi (CNARED), an organization formed in July in Addis-Ababa by members of civil society and the opposition, including two former Burundian presidents.

The Arusha Accord, signed in 2000 after long negotiations and considered the foundation stone of the new Burundi, ended years of civil war between the army, which was Tutsi-dominated at that time, and the Hutu rebellion of which Nkurunziza was a part.

Bujumbura says CNARED is a “terrorist organization” and has issued arrest warrants for some of its members for alleged involvement in the failed May 2015 coup attempt. According to Burundian Foreign Minister Alain-Aimé Nyamitwe, the “putchists” should be brought to justice, not to sit around a negotiating table.

The opposition continues to demand Nkurunziza’s departure, saying his re-election in July violates the Arusha Peace Accord and the Constitution. The Presidential camp refutes this.

“Let us pray”

So what hope is there that Burundians will resume dialogue after the missed rendez-vous in Arusha on January 6?

The Burundian crisis will no doubt be on the agenda of the next African Union summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, at the end of the month. But will the Heads of State manage to get a change of heart from the Burundian authorities? This is unlikely, according to numerous observers. It is also likely that Burundian President Nkurunziza, who according to his Rwandan counterpart Paul Kagame has been "hiding” since last May, will not even go to Addis Ababa.

Meanwhile African Union Commission President Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma has written to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon asking for full UN support for the deployment of MAPROBU. The Security Council has not yet answered, but it is likely that Russia and China, two permanent members of the Council, will not favour such support.

The United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) has not been sitting idle all this time. It has been studying possible scenarios and corresponding responses required by the international community, especially if Burundi were to spill over into “violence with a clear ethnic dimension and on a much greater scale and intensity, with potential incitement to commit serious crimes, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide”.

In a leaked confidential memo to the UN Security Council, DPKO boss Hervé Ladsous admitted that in such a scenario, “the United Nations is ill-equipped to mount the type of peace enforcement operation that may be required”. The document notes that it would be necessary to obtain a mandate from the UN Security Council, troops from member countries and “a form of consent of the Government of Burundi”. Ladsous stresses that this would be a measure of last resort and that UN peacekeepers “are not an expeditionary force”. Under such a scenario (worst case), the document says that “civilian protection will be limited to some sites in Bujumbura, despite the strong likelihood that civilians may be threatened across the country, as current trends indicate”.

“Let us pray to God that things do not reach that point,” says a Burundian Evangelist now in exile in the Ugandan capital Kampala.