In the fall of 2015, three young men escaped the Lord’s Resistance Army, a brutal rebel group that is known for the abduction and conscription of children. The three youth hiked through vast tracts of forest and remote land to the main road where they came across local hunters who brought them to Obo, a town in southeast Central African Republic (CAR). After spending between 11 months and 3 years in the LRA, their most immediate needs were clean clothes, a warm meal and a medical check-up. But another journey for them was just beginning. It is a journey that former abductees and members of their home communities take together -- a search for understanding and healing from the trauma of the LRA’s unpredictable violence. Two recent reports by the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative detail the experiences of those indoctrinated into the LRA, and the challenges communities face in LRA-affected areas.

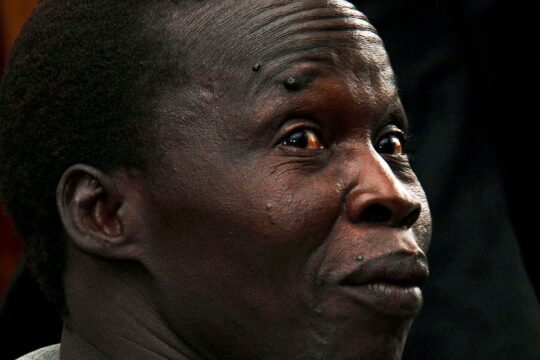

The LRA, led by ICC-indicted Joseph Kony, emerged in the 1980s in northern Uganda, where it became notorious for killing, raping, abducting children and mutilating victims. In 2005, increasing military pressure pushed the LRA out of Uganda and in to neighboring countries. Presently, the group continues to cause widespread displacement and spread terror in northern Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and the Central African Republic. Although indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) since 2005 for war crimes and crimes against humanity, Kony and his high-level commanders remain at large. The only LRA accused person now in the ICC’s custody is former child soldier turned LRA commander Dominic Ongwen, whose confirmation of charges hearing is set to start before the ICC on January 21.

The HHI report looked at all four countries where the LRA is or has been active. It focuses particularly on how local individuals and communities have created structures to support resilience and self-protection in the face of chronic, unpredictable violence. Participants in the research describe innovative ways to draw together, adapting new systems to overcome challenges related to insecurity. These include creating early warning information networks, forming peace committees to welcome LRA returnees back into civilian life, and starting economic cooperatives. Yet, the problem of addressing the mental health issues that arise from witnessing and experiencing violence are some of the most intractable and difficult to address in all of the four countries visited for the research.

Violence in LRA affected territories affects not only abducted who are forcibly taken by the group, but also traumatizes all members of affected communities. People describe facing psychological problems like aggression, anxiety, depression and intrusive memories.

Community leaders, religious figures, women’s associations and other groups have stepped forward to try to address the psychological needs of their communities. These local efforts include offering counseling, conducting educational campaigns, leading groups, and spiritual healing through prayer or traditional rituals.

Despite these avenues for healing, participants in all field sites visited by the researchers expressed a pressing need for more formalized trauma healing work. For instance, one nun noted she was responsible for caring for dozens of children abducted by the LRA. She didn’t have the knowledge for how to help the children process their experience, and the result was that both she and abductees were left feeling helpless in the face of their trauma.

As part of the project to support community resilience, the HHI research team partnered with a clinical psychologist who had experience working in Africa to create a “trauma healing toolkit.” The toolkit contained a curriculum to create workshops, trainings and radio messages to support trauma counseling, mental health understanding and to promote self-care and coping. These materials were then shared with Invisible Children, one of the only NGOs with long-term experience working in all LRA-affected countries.

Invisible Children organized two mains workshops with these materials: one with journalists from four FM radios in CAR and another with members of seven community-led peace committees active throughout eastern CAR. Journalists from four field locations focused on ways to support wide trauma healing initiatives within their communities that were highly affected by LRA. After a five day workshop focusing on basic psycho-education and self-care skills, journalists produced two radio shows aimed at equipping members of the community to understand trauma and support their family and neighbors who face mental health challenges. A representative of a local NGO working with LRA returnees recently said that, more than anything, the returnees she cares for need a space to feel safe and not be judged. Through the toolkit she feels her staff is now equipped to provide just that.

Jocelyn Kelly is the Director of the Women in War Program at the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative where she designs and conducts research related to gender in conflict. Pauline Zerla is the Former Deputy Coordinator at Invisible Children; she manages and designs peacebuilding programs focusing on youth, media and the reintegration of former combatants in Sub-Saharan Africa.