From Sukhumi, Abkhazia

“Geneva peace talks are not leading to any conclusions. It is just a false assumption that we can live -again- alongside Georgians. It cannot come true” – Ruslan, a veteran of the 1992-1993 Abkhazian-Georgian war is clear when it comes to the future relations between these two Caucasus neighbors. He is an Abkhazian patriot, full of reluctance towards people from Georgia, dreaming of an independent state - his place on earth, but also on the geopolitical map of Euroasia. Long way to go… Ruslan is a citizen of Abkhazia, the so-called quasi-state, formally still an integral part of Georgia.

Transitional justice in post-USSR region – the lacking element of the socio-political landscape?

Transitional justice discourse rarely touches on the issue of unrecognized states (regimes de facto), especially those based in the post-Soviet space. Debates concentrated mainly on the African conflict and post-conflict societies, subsequent interventions of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in fragile environments or the relevance of the truth-seeking and truth-telling bodies (again mostly in Africa), as it seems, do not perceive the former USSR republics as a ‘proper place’ for transitional justice. It is visible, not only in a sense of implementation of particular post-violence instruments, but also in a way that this part of the world is still not in a ‘proper time’ of its history to truly transform itself. To talk honestly about legacy of Soviet Union’s past evils and its disintegration that led to the establishment of numerous ‘new’ states in the Eastern part of Europe and many bloody conflicts as those between Georgia and Abkhazia, Moldova and Transnistria or Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. All of them have their strong geopolitical and legal implications until today.

The Ukrainian crisis, commenced by the ‘Revolution of Dignity’ protests on Maidan Nezalezhnosti in Kyiv, through the annexation of the Crimean peninsula by the Russian Federation, up to the ongoing armed conflict in Donbas, ‘highlighted’ the necessity of using some transitional justice mechanisms. As we all know, the ICC, as a result of two ad hoc declarations, issued by the Verkhovna Rada, the Ukrainian parliament, took under its preliminary examination procedure the possible international crimes committed during the ‘Maidan demonstrations’, as well as on the territory of conflict in the east of Ukraine. At the same time, neither the amnesty provisions, nor the special autonomy status for Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts proposed by the president Petro Poroshenko came into force – mostly because of the negative attitude of the leaders of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk Peoples’ Republics. Nevertheless, this situation showed one simple thing: in order not to disintegrate a sovereign state (such as Ukraine) and allow for the creation of de facto regimes on its territory, transitional justice mechanisms should go ‘hand in hand’ with the military or political means. The main objective behinds this is ‘to attract’ common people and build a platform of understanding between adversaries.

Is it really possible? The project of the so-called ‘Novorossiya’ (‘New Russia’) - composed of Donetsk and Lugansk Peoples’ Republics - is now frozen, but at any time can materialize again. Thus, in accordance with the ‘lessons learned’ postulate, let us have a look at one, ‘constantly frozen’ situation of quasi-states in the post-USSR region. Abkhazia – the existence of which is secured by Russian troops – can serve as an example of almost 25 years of tough relations between the legal and de facto authorities of the two sides of the dispute. These relations also involved some of transitional justice elements (understood quite broadly), even though those which mostly failed.

Cultivating past evils in Abkhazia

“Everyone perceives us as a next republic in a composition of the Russian Federation. It is not true – becoming the part of Russia is our ‘plan B’. On the other hand, I do not see any chances of forming one state with Georgia. This phase of a history is over” – words of Irakli Hintba, a policy advisor of the Abkhazian president Raul Khajimba, do not leave any room for further discussion. Abkhazia simply cannot reintegrate with Georgia – that is the common understanding of the situation in Sukhumi. Completely different voices can be heard in Tbilisi. “Keep it in mind, you are going to just the other region of Georgia” – reminded us very strongly people in Zugdidi, the last Georgian town before crossing the border on the bridge over the Inguri river.

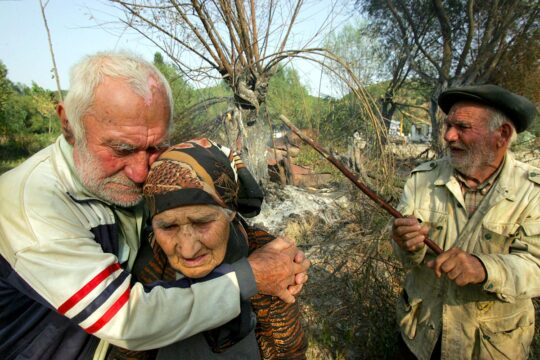

The war between Abkhazians and Georgians started in late summer of 1992, with an attack of Georgian forces on its north-east province. It was a direct result of the nationalistic tendencies in Georgia (‘strengthened’ by the president Zviad Gamsakhurdia’s narrative) and a dissolution of USSR. Before the war, in Abkhazia there lived around 240.000 Georgians (Megrelians to be precise), which constituted around 40-45% of the whole population – comparing to less than 100.000 ethnic Abkhazians. Most of them lived in ‘Megrelian’ cities in the southern part of the province, like Ochamchira, Tkvarcheli, Gali, but also in the capital – Sukhumi. Today, in 2016, the number of Georgians decreased to less than 15%, even though some of the war refugees returned to their houses in Gali region. The number of Abkhazians is a bit bigger comparing to the early-90s, but, because of the Georgian exodus, they became now the biggest national group in the country (among Russians, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Ukrainians and others).

Ruslan, our guide in Abkhazia, during the war was a military scout, fighting on a frontline next to the Gumista River. The whole Novy Rayon (New District) full of new block of flats, built in a typical socialist style of architecture, suffered a lot of damage. The same fate befell one of the most modern sports complexes in late-Soviet times, located in the closest neighborhood of the New District. Frankly speaking, even today these buildings look like war ended just a week ago, not in 1993. Some old inhabitants came back and renovated their apartments, having as ‘neighbors’ big holes after the mortar fire. People like Ruslan, directly involved in the warfare, openly hate Georgians. Others, like the younger generation of Abkhazians, simply do not know their Georgian peers.

These days, Abkhazia is informally split into two parts – with Sukhumi in the middle as a natural border spot. From the capital city to the borders with Russia, we can drive on a newly build highway constructed with the Kremlin money and observe beaches, restaurants and hotels packed with numerous tourists, mostly from Moscow and Petersburg. The other direction, towards the Georgian border, is rather depressing and grim – abandoned cities, weedy villages and just a tiny part of the Megrelian population that used to live in the Gali region before the war. One country, two different worlds.

What post-war mechanisms, if any, were applied in Abkhazia? To some extent, we can talk about the refugee return program. Sergey Shamba, the former ‘minister of foreign affairs’, told us that Abkhazian government could not agree to let Megrelians resettle in other regions than Gali. Around 50-60.000 Georgians came back to Abkhazia; nevertheless still a lot of refugees from the 1992-1993 conflict remain in Georgia. It should be emphasized that some of them for more than 20 years have lived in refugee camps. Because of the money given by international donors, mostly during the term of the former Georgian president, Mikheil Saakashvili, few of those camps have been ‘transformed’ into very comfortable housing estates; however, this is not the case of all refugees. A good example is Zugdidi town, where some of the war fugitives dwell in nice apartments built with the German government’s money, while others have to organize their life in the corridors of the old school building. The UN General Assembly in its 2013 resolution (indirectly) reminded the Abkhazian authorities of the Megrelians’ right to return to their properties in Tkvarcheli or Ochamchira regions (so outside the Gali province).

On the other hand, after the so-called ‘Revolution of Roses’ (2003), Saakashvili tried to enforce the reintegration of Abkhazia into Georgia. His policy of unification of the whole country and security of the territorial integrity was widely promoted abroad, mainly to gain the international acceptance and support (successfully – EU and USA funded, for instance, a holistic reform of the army). As a result, Georgian forces took control over the Kodori Valley (in the eastern part of Abkhazia, known also as ‘Upper Abkhazia’). Soon afterwards, Saakashvili installed the pro-Georgian Abkhazian government (in exile), based until that time in Tbilisi. The situation changed rapidly in 2008, when Abkhazians displaced Georgians from Kodori, tactically using the time of Georgian-Russian 5-day war in South Ossetia. Saakasvhili’s reintegration policy dramatically collapsed.

Theoretically, the Geneva peace talks formula should make it possible to find some solutions in the Abkhazian-Georgian dispute. But that is only theory since two sides cannot agree on fundamental issues – the sovereignty and territorial integrity stipulated by Tbilisi and full independence from Georgian jurisdiction postulated by Sukhumi. Maksym Gvindzhia, the other former ‘minister of foreign affairs’ of the Abkhazian government, is sure that the international community made a crucial mistake by joining the two cases: Abkhazian and South Ossetian in one format. “Underestimating the Caucasus pride and not seeing the differences between those two ethnicities only discouraged Sukhumi from the international negotiations” – said Gvindzhia, during our interview in one of the most modern office blocks in the Abkhazian capital.

Is Abkhazia moving towards the full integration with the Russian Federation (which, in fact, recognized the regime in Sukhumi in 2008)? Not necessarily, even though after the Russian-Abkhaz Agreement On Alliance and Strategic Partnership signed in 2014 vectors of the Kremlin and Sukhumi policy are put more in one direction. Troops of the Russian Federation, officially called ‘the peacekeeping forces’, openly provide a border control and supervise the so-called ‘visa regime’ (each foreigner willing to visit Abkhazia must apply for a special permit).Yet, Abkhazian leaders prefer to become a fully sovereign state, outside the full control of Moscow – or to remain the quasi-state. “Sometimes it is better to be unrecognized, you do not have to comply with international law” – cynically concluded Gvindzhia. At the same time, (re)building one common state with Georgia is simply not possible. The war legacy and past evils are rather ‘cultivated’ by Abkhazians (like a ‘ghost building’ of the Soviet Abkhazian authorities on the main square in Sukhumi). On the other hand, Georgians talk about the ethnic cleansing and the Sukhumi massacre of Megrelian inhabitants of Abkhazia. Thus, it is very difficult to find one point of understanding. Today, the ‘common’ spot can be found on the border between the two entities on the bridge over the Inguri river. It is the spot, where most of the Megrelians refugees staying in Georgia cannot cross the border to visit their families living on the Abkhazian side of the frontier.

Next de facto regime – is Donbas definitely lost?

The Abkhazian case serves as a laboratory of really difficult relations between de iure and de facto authorities and their subsequent failure. The ongoing hatred between the two nations prevented the successful implementation of the post-war mechanisms. All of these resulted in losing contact between younger generations of Georgia and Abkhazia and cultivating the memory of heinous crimes committed during the 1992-1993 war and in the aftermath of the conflict. As it seems, the Geneva Peace talks undertaken under the auspices of the international community are just shallow diplomatic events, since the two parties to the conflict cannot reach satisfactory conclusions for Tbilisi and Sukhumi.

Today, the question remains whether the Abkhazian scenario (as well as e.g. Transnistrian) can be repeated in the case of Ukraine. Will the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics finally disintegrate with Kyiv administration? Will they join the Russian Federation, as it was illegally done before by the Republic of Crimea? Paradoxically, these days Kremlin pushes for reintegration of Donbas with Ukraine to have a powerful tool of its influence over the Ukrainian authorities. In the eyes of Moscow, pro-Russian voters, Russian-speaking inhabitants of Donetsk and Luhanks oblasts are able to stop the Ukrainian march towards Western states, symbolized by the post-Maidan government. Importantly, Ukraine has already implemented a bunch of transitional laws directed at de-communization of the country and lustration of public officials, working in the Viktor Yanukovych’s administration.

This is the reason why Kyiv should craft its policy very carefully in order to solve the problem of its eastern part. Diplomatic and military means are necessary; however, it is very significant not to break ties of people living in Donbas with the rest of the Ukrainian population. Petro Poroshenko and Andriy Yaceniuk, the prime minister, are quite clear. They want to punish all those who are responsible for crimes that occurred during the Maidan protests in Kyiv and the conflict in Donbas (inviting the ICC is an evidence). These attempts should be accompanied by the policy of reintegration – transitional justice legacy of institutional reforms or social reconciliation is a proper tool-kit for achieving the Ukrainian primary goals. Importantly, Poroshenko’s amnesty proposal for Donbas fighters– fully in compliance with the international law and the case-law of international tribunals, which was one of the solutions – failed. Nevertheless, such initiatives are good example of potentially successful means of avoiding the Abkhazian, or another post-USSR scenario, in Ukraine.