As part of their defence before the International Criminal Court (ICC), Laurent Gbagbo’s lawyers have chosen to attack. First they attacked Gabgbo’s successor, current Ivorian president Alassane Ouattara, who “wanted to take power by force”. And then France, which they say “had long been secretly preparing” Gbagbo’s ouster. Gbagbo’s co-accused Charles Blé Goudé chose to attack the portrait of him presented by the Prosecutor.

Whereas the prosecution portrays Blé Goudé as “issuing orders against those perceived as supporters of Alassane Ouattara”, he presents himself as a man of peace. Both men also contest the “simplistic” version of the crisis laid out by prosecutor Eric McDonald. Although the prosecution admits that crimes were committed on both sides after the partition of the country that followed the failed coup on September 19, 2002, the defence says it has not taken account of the forces present and their respective actions during the period in question from November 27, 2010 to April 12, 2011.

The former Ivorian president and his former Youth Minister are charged with crimes against humanity committed after the November 2010 presidential elections. The prosecution will now call the first of its 138 witnesses to the stand.

Did Gbagbo target civilians or combatants?

This is the focal point of Gbagbo’s defence. His lawyers say he never targeted civilians. According to them, the Defence and Security Forces (regular Ivorian army) were not faced with peaceful demonstrators marching towards the Ivorian State TV and radio (RTI) on December 16, 2010, as the prosecution claims, but rioters. In deploying the army and police, they say Gbagbo was only doing his duty in the face of combatants staging a rebellion. The clampdown on this march left dozens of people dead.

Without support from Burkina Faso, the New Forces (rebels at that time) would not have been so powerful, argued Jennifer Naouri, a member of Gbagbo’s defence team. She claimed that Burkina Faso was “France’s armed support in the region”. Defence lawyers evoked France’s role at length, talking about colonization, the independence of Côte d’Ivoire and support to Alassane Ouattara. Ouattara was “liaising with French military strategists throughout the duration of the crisis”, said lawyer Emmanuel Altit, who alleged that “French military ‘planes were constantly delivering heavy weapons” to pro-Ouattara forces in February and March 2011. He also claimed that “French special forces organized the offensive of March 2011”. It was they, he said, who “cleared the terrain for pro-Ouattara forces” as they marched on Abidjan. Gbagbo’s arrest on April 11 by Ouattara’s forces was made possible by French support, he added. The defence also contested allegations that Gbagbo drew up a plan with his close aides to keep power “at any price”. Dov Jacobs, speaking for the defence, questioned the authenticity of a register of visits to the Presidency, which is a key piece of prosecution evidence. He added that “members of the special services walked off with all the archives” when the Presidency was taken.

A key piece of prosecution evidence

Charles Blé Goudé’s lawyers also evoked the visits register, seeking to show that, according to them, Blé Goudé only went to the Presidency 18 times in 106 days and that on December 1, New Forces leader Guillaume Soro was received like others, including the Accused. Lawyer Alexander Knoops argued that “it was Guillaume Soro himself who on the eve of the march on RTI gave orders to use violence” and that this march was not peaceful. The defence tried to demonstrate that Blé Goudé was “a man of justice”. To this end they showed videos of speeches he has made in the last ten years, with Blé Goudé and the Muslim community of Gagnoa calling for unity between Ivorians. “Perhaps the Prosecutor has mistaken democratic expression for crimes against humanity?” said lawyer Clédor Ly, adding that it was a pity the Prosecutor had “no videos showing Blé Goudé’s young supporters committing violence”.

An ethnic and religious conflict

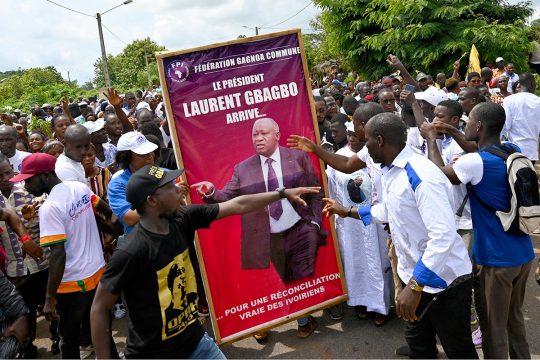

Only a handful of loyalists were listening to the Accused from the public gallery. “The civilian population and I chose the democratic path,” claimed Gbagbo’s co-accused with the confidence of his charisma. “Laurent Gbagbo never sent me to commit crimes,” nor to “encourage the youth to go and commit crimes”, said Blé Goudé, sporting a badge of the Pan-African Council for Justice and Equality (COJEP) on his suit. At one point, he marked his distance from the former president. “Has Côte d’Ivoire had leaders who made war-mongering speeches?” he asked, before replying in the affirmative and saying he tried to get Gbagbo, Ouattara and Henri Konan Bédié around the same table. He claims to have acted as a democrat. “In 2010, it was the Constitutional Council that pronounced President Laurent Gbagbo the winner, it wasn’t me,” said Blé Goudé, who tries to portray himself as someone who “respects the laws of the country”, to which he said he only “submitted”. Blé Goudé then said that “Laurent Gbagbo should not be in prison” and that he represented “the possibility of reconciliation”. Throughout their arguments in court, the lawyers slammed the prosecution and victims’ representative for trying to portray the Ivorian crisis as ethnic and religious.