“They arrested me in September 2013 when I was at home with a group of musician and film maker friends. The police burst into my house with batons and clubs. They beat us up. You can’t talk to them, they just beat you up, that’s all!”

These are the words of young film maker Néjib Abidi in a Human Rights Watch (HRW) video entitled “All this for a Joint”. The video was presented this week by four NGOs -- HRW, Lawyers without Borders (ASF), International Alert and the Network of Tunisian Justice Monitors (ROJ) – to call for reform of Tunisia’s tough law (Law 52) on consumption of drugs including cannabis (zatla in Arabic). This soft drug is widely used in Tunisia, especially among young people, budding artists and in the poor parts of the big cities.

In the video, Néjib Abidi describes brutal police methods to force those suspected of using cannabis to take the test. “They make you urinate in the parking lot. The police brought tubes and held us by the neck. Then they make you undo your trousers and urinate,” he says.

As well as being humiliated and insulted, some have even been tortured during interrogations for drug related offences, according to the Tunisian Justice Monitors. As of December 2015, there were 7,451 people imprisoned in Tunisia under Law 52, of whom 70% for cannabis consumption and 30% pour distributing and selling it, according to the HRW report, published on February 2, 2016. They represent 20% of the state prison population.

A journey to hell

Law 52, dating from 1992, provides for prison sentences of one to five years (for repeated offences) in jail and a fine of 1,500 Dinars (700 Euros). It does not allow the judge to reduce the sentence for mitigating circumstances. This law “is part of the repressive arsenal of the former regime of president Ben Ali,” says ASF head of mission Antonio Manganella.

The suffering of those convicted under Law 52 does not stop with the sentencing, which most human rights organizations in Tunisia consider too harsh. Their voyage into hell continues in overcrowded jails which “are themselves torture” according to Amna Guellali, who heads the HRW office in Tunis. Some prisons are filled to 150% of capacity, according to the latest Tunisia report from the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

For smoking a joint in private, young people aged 18 to 30 are thrown into jail alongside hardened prisoners, in promiscuous conditions considered inhumane.

When they are released, now with a criminal record, they are stigmatized by society and excluded even more from the labour market.

“The most vulnerable, those in the poor suburbs, often get involved in drug dealing as the only way they see when they can’t get a job,” says Mehdi Barhoumi of International Alert.

“The Law has failed”

“Available statistics show that the majority of those convicted for taking drugs serve their sentences and then re-offend,” says the Network of Tunisian Justice Monitors, in a report on 23 years of Law 52. “Studies on the ground show the rate of re-offence is around 54%.” The Network of Tunisian Justice Monitors was founded in 2012 by the Order of Tunisian Lawyers, the Tunisian Human Rights League and ASF to push for adoption of international standards in Tunisian criminal law.

“Law 52 has failed,” adds the same report. “It has neither stopped offenders, nor stopped the growing numbers, nor ensured rehabilitation of drug users.”

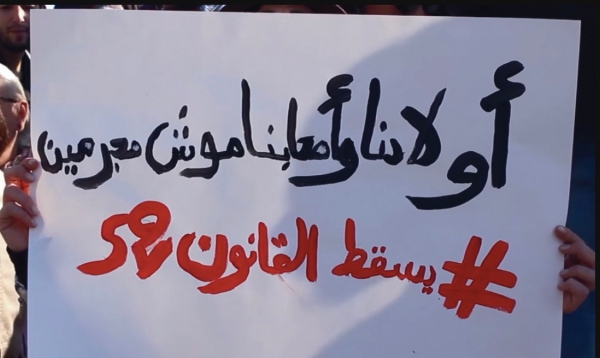

Cases of convictions under the cannabis law have multiplied in recent months following police raids on people suspected of terrorism. Under pressure from civil society organizations, artists and public personalities, the government on December 30 approved a draft amendment to Law 52. It includes some improvements, including abolition of mandatory sentences for both first-time and repeat offenders and greater emphasis on access to treatment services for addiction.

But Human Rights Watch says the draft amendment still raises some concerns with regard to human rights. “By maintaining the option of prison sentences of up to one year for repeat use and possession of illegal drugs, the bill ignores calls from international experts on human rights and health urging countries to eliminate custodial sentences for drug use and possession,” says HRW. It also introduces a new offence of “public incitement to commit drug-related offenses.”

“This new provision, as it is written, is contrary to freedom of expression,” warns Amna Guellali. “It could be used to prosecute members of groups advocating for the decriminalization of drugs, rappers and singers whose songs talk about zatla.”