Lesson learned: always check the microphones. Just after the start of the Hague trial of former Côte d'Ivoire president Laurent Gbagbo, prosecutor Eric MacDonald accidentally revealed the names of four anonymous prosecution witnesses within reach of a live microphone. The names were heard in the courtroom and the public gallery, and the recordings have been shared on social media.

The clearly disconcerted presiding judge, Cuno Tarfusser, wondered whether this incident “of utmost and inexcusable gravity” was due to “recklessness, superficiality or stupidity.” He did not wish to “speculate about something else”, alluding to hypothetical foul play. The judge formally apologised to the witnesses and ordered an internal investigation.

The incident highlights the difficult balancing act between holding transparent trials and prioritising witness and victim protection. And having observed the prosecutor’s opening statements from the public gallery, I saw the reactions of the two defendants' close supporters – reactions that revealed the deep fault lines in this case.

Gbagbo served as president of Côte d’Ivoire between 2000 and 2010. In 2010, he disputed the results of presidential elections that he officially lost, sparking a five-month political crisis that left more than 3,000 people dead. He is on trial with Charles Blé Goudé, the longtime leader of a youth movement known as Jeunes Patriotes (Young Patriots). Gbagbo appointed him minister for youth in 2010 during the crisis.

Gbagbo and Blé Goudé were transferred to the International Criminal Court in 2011 and 2014 respectively, and were charged as indirect co-perpetrators of crimes against humanity allegedly committed as part of a plan to keep Gbagbo in power “at any cost”. The two have both written tell-all books in which they refute such allegations.

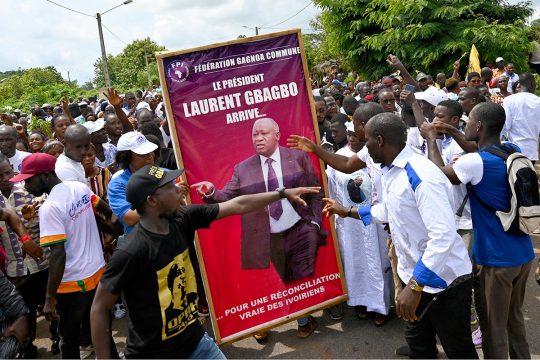

I was at the ICC on the first day of the Gbagbo-Blé Goudé trial and waited with about 300 of their supporters outside the court’s shiny new permanent building in The Hague. One woman told me, only half-jokingly: “They built a new building just to try our president!” Protesting the portrait that was painted of Gbagbo as a dictator during the 2010-2011 crisis, another fan chanted sarcastically: “Give us back our dictator!”

Inside the court, diplomats, NGOs, journalists and members of Gbagbo and Blé Goudé’s close entourage filled the public gallery. Following the trial through headphones with simultaneous French and English translation, audience members have a clear view of the judges, prosecution and legal representative for victims teams on the left, both defence teams on the right, and both defendants sitting behind their respective representatives. For identity protection concerns, audience members cannot, however, see witnesses and victims testifying.

From inside the courtroom, one can look up and see members in the public gallery. After the second day’s hearings, Gbagbo stood up and saluted his supporters – who waved back ecstatically and left the gallery singing the Ivoirian anthem.

Disbelief, guffaws, and amulets

Since all the ICC’s criminal charges concern acts that took place in Abidjan, much of the evidence will be photo and video footage of the urban warfare that took place there. But rumours and conspiracy theories are rife in Côte d’Ivoire – and there are suspicions that evidence of this sort can be fabricated and altered.

Rumours have spread that video footage showing women lying on the ground, wounded from gunfire after an attack on a pro-Ouattara march in the Abobo neighbourhood of Abidjan, had been fabricated. When the prosecutor showed the graphic video in court, many of the pro-Gbagbo supporters reacted strongly, contesting its authenticity. For others, the dissonance between the gravity of the women’s injuries and the doubts of some supporters was jarring.

Another sticking point has been the relations between Ivoirian ethnic groups. As part of his case, the prosecutor wants to establish that Gbagbo and his “inner circle” encouraged crimes against perceived Ouattara supporters, who (very broadly) often share some combination of various characteristics: origins in northern Côte d’Ivoire and/or other West African countries, Muslim faith, and/or Dioula ethnicity.

The prosecution accused Blé Goudé of having ordered pro-Gbagbo youth to monitor “foreigners” and search for those who wore amulets known as “gris-gris”. At this, the Gbagbo supporters in the public gallery guffawed. To them, Ivoirians are not as ethnically divided as the prosecution contends – “gris-gris” are supposedly not worn exclusively by northerners and therefore couldn’t be a target sign for persecution.

The impression that foreign lawyers are trying Ivoirians without understanding the country’s nuances is a rallying point for those who contest the ICC’s legitimacy. But, ultimately, it is up to the judges to weigh this scepticism against well-documented evidence of persecution of pro-Ouattara supporters.

But who gets to determine whether or not a trial is political?

Problematic partiality

In her opening statement, the ICC prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, proclaimed the trial apolitical, emphasising that it is not trying to determine either who won the elections or who should have won them. I immediately heard a chorus of incredulous groans from Gbagbo’s supporters. As they see it, this trial is the finale of a campaign that set out to oust Gbagbo as president with the help of France, a campaign waged first with hijacked elections and now with an instrumentalised ICC.

One of the most trenchant criticisms of the trial so far is that, by trying only the Gbagbo side without trying members of the Ouattara side (some of whom are suspected of serious crimes), the court is revealing its political nature. This line of criticism is what professor of law Darryl Robinson calls the “apologia” critique: the idea that by not trying members loyal to the incumbent Ouattara, the ICC is deferring to politics, thereby lacking the “principled independence” and “critical bite” that a court should have.

But the prosecutor’s strategy needs to be viewed in light of the ICC’s very particular nature. The Office of the Prosecutor requires co-operation from governments in order to bring a case to trial, and states' refusal to co-operate has led to cases being suspended before. At the crux of this trial’s inherent politicality is the tension between pursuing effective yet impartial prosecutions, bearing in mind all the conflict’s victims.

It is likely the trial will last several years. If so, the verdict will be handed down just in time for the run-up to Côte d'Ivoire’s next presidential elections in 2020 – when Gbagbo’s supporters can channel their reaction to the verdict into the political process.

This article was published by The Conversation