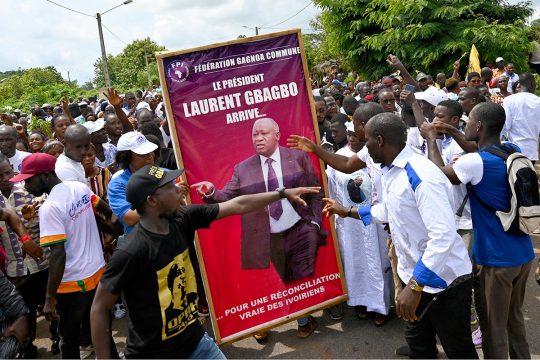

In Côte d’Ivoire, people have very different views about the trial of their ex-president Laurent Gbagbo and his former minister Charles Blé Goudé, which started on January 28 at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands. The two are accused of crimes against humanity for their alleged role in violence that followed elections in late 2010 and which left more than 3,000 people dead. This historic trial divides not only the political class but also civil society activists, notably in the economic capital Abidjan.

Five years after the events, the moral and psychological scars do not seem to have healed. In fact they are as palpable as ever. The trial of Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé – founder of the Pan-African Congress of Young Patriots (COJEP), which described itself as an anti-colonialist movement but the ICC sees as a militia – is highlighting the deep divisions between Ivorians and the limits of the reconciliation process.

Yopougon, a working-class district of northern Abidjan, has always been considered as Laurent Gbagbo’s stronghold. Seated round a table in a bar there near the Place Ficgayo, about 100 supporters of the ex-president are following his trial on a foreign TV channel. Like good pupils in a classroom, they listen attentively to the charges against the two co-accused as laid out by ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda. They do not want to miss anything. Here, there are only Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) activists from the Aboudramane Sangaré wing of the party. Sangaré, a founder FPI member and advocate of “Gbagbo or nothing”, now leads the party hardliners and is considered by many of its activists as the “guardian of the temple”. Sangaré’s supporters contest the legitimacy of Pascal Affi Nguessan as FPI president and say they will only engage dialogue with President Alassane Ouattara if he gets Gbagbo and all other imprisoned FPI activists freed. They are all convinced of Gbagbo’s and Blé Goudé’s innocence.

There’s a lively discussion as they drink their beer. Some of them see this trial as a parody of justice. They see the ICC as subject to the Western powers, especially France. They reject the idea that only their champion Laurent Gbagbo should be accused, whereas “he always promoted democracy and dialogue”. In general, the “frontists” (FPI activists) are convinced that this is victor’s justice designed to keep Gbagbo out of Ivorian politics and allow Ouattara to govern without real opposition. Nevertheless, other FPI activists say they believe in international justice. They hope the trial of Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé is an opportunity to shed light on the truth they think has always been manipulated, if not falsified. “It’s also an opportunity to have former rebels that supported Alassane Ouattara and occupied three-quarters of the country for nearly ten years appear before the Court,” they say. All the “frontists” agree on one thing: “Laurent Gbagbo will be acquitted and return to the country to resume the struggle where he left off,” they say. But what struggle? In chorus they reply that it is the struggle for Côte d'Ivoire’s veritable national sovereignty and the definitive liberation of Africa.

Divided opinion in the ruling party

Inside a “gbaka” (public service minibus) to Abobo, another working-class district in the north of Abidjan, talk is also of the Gbagbo trial. Abobo was the scene of some of the bloodiest episodes of the post-election crisis. It was here that on March 17, 2011, a bombardment of the marketplace, attributed to pro-Gbagbo forces, left 7 dead, all women. In the stronghold of the ruling RDR party, opinions are divided. Some RDR activists want Gbagbo and Blé Goudé kept in the ICC prison in Scheveningen, The Hague. But unexpectedly some of them want Gbagbo freed. They are sure this would change nothing in the current political configuration of the country. In support of this argument, they point to Alassane Ouattara’s crushing victory in the 2014 presidential elections, with a Soviet-like score of 83.66% of votes.

Here FPI supporters prefer to remain silent, they say, to prevent reprisals from the Republican Forces of Côte d'Ivoire (FRCI), the new national army. They prefer to leave it to God to free their “comrades” Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé.

They consider themselves the first victims of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, in contrast to the view put forward by international opinion.

Another district, other realities. Cocody, the chic part of Abidjan, lies next to Abobo. It is here that most of the Ivorian intelligentsia live. Here, certain people are calling for Gbagbo’s acquittal, so the country can have real reconciliation.

One of Cocody’s inhabitants goes even further. Brandishing his card as a member of the RDR, the ruling party of which he has been an unconditional supporter for some 20 years, he says he is disgusted that most of ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s witnesses are from the Dioula ethnic group, whereas he belongs to the Bété group of Gbagbo and Blé Goudé. “There are not just Dioulas in the RDR,” he explains, “there are members of all ethnic groups, like in the FPI. There are Sénoufos, Baoulés, and so on. I am frustrated by what has happened.”

Black Out

This frustration is shared by many other Ivoirians who say they dislike the way the media has covered this trial. They reproach public broadcaster Radiotélévision ivoirienne (RTI) for its total blackout of the trial, in which an important part of Côte d'Ivoire’s post-independence history is being written. They do not understand why the national broadcaster has chosen silence, and think this is a wrong choice.

And the official position of the RDR? Its spokesman Joel N'guessan denounces the decision of Gbagbo and Blé Goudé to plead not-guilty. He says the FPI and its supporters “have never been able to recognize even once in their political lives their responsibilities for what happened. They have always maintained that what happened through their political actions was the fault of others.”

Joel Nguessan’s view is not shared by some human rights organizations which denounce what they call “the bias of Prosecutor Bensouda”. Up to now, they point out, no-one close to Alassane Ouattara has been troubled by the ICC. They say this is not good for reconciliation. They hope the Prosecutor will also investigate the crimes of the ex-rebels who have become the new national army. To do that, she will have to go back to the start of the Ivorian crisis in 2002 and even further back to the coup d'état of 1999.

In summary, five years after the crisis, tensions remain visible and show that reconciliation is far from being a reality in Côte d'Ivoire. Many Ivorians think, rightly or wrongly, that this is due to a lack of political will.