March 8 is International Women’s Day, and one of the main focuses this year is pushing for parity. Women in conflict countries are often excluded from peace processes. Back in 2000, the United Nations passed Resolution 1325, calling for women to be involved in all levels of peace making and peace building. So, fifteen years on, are we getting parity for women in peace processes? JusticeInfo put the question to Jocelyn Kelly, head of the Women in War programme at the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative.

Jocelyn Kelly: I think 1325 created a beautiful roadmap for the engagement of women in conflict resolution and peace processes, but today we are still very much at the beginning of that journey and I think we struggle to make progress on the lofty goals that 1325 laid out. For instance some of the latest numbers that I have seen are that women are only engaged in 14 percent of peace processes around the world, which is clearly not the vision that is codified in the language of 1325. But despite women’s very low engagement in peace processes, we found that when women are substantively engaged in peace negotiations and conflict resolution, those processes are actually much more likely to be successful. I think it’s critical to have high-level commitments to women in peace building, and I think 1325 is a good beginning to that process. Now we are left firstly with expanding the mission, so we recognize that women’s issues as a whole are security issues, and that security issues are women’s issues. I also think we have to do a better job of implementing 1325.

JusticeInfo: What do you think are the main reasons that Resolution 1325 remains largely just high-flying objectives?

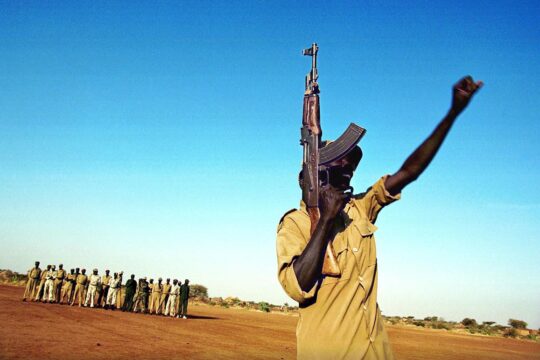

JK: Well, there is a certain lack of political will. I think in some ways we have outdated notions of what peace resolution and peace processes should look like, and we continue to reward the most violent and abusive armed groups for perpetrating human rights abuses without beginning to expand our understanding of who the “actors” to a conflict truly are. And when you look at who is a party to a conflict and who is an actor in the conflict, then women are half the population and often experience an undue burden of violence and of health effects of conflicts. So if we begin to re-define who are those engaged in the conflict and who are those affected by it, then I think we would do a better job of engaging women in peace processes. I also think that sometimes we are frankly lazy about looking for the remarkably active, powerful and engaged women’s groups that exist in countries affected by conflict. A lot of times these groups may not look like what we expect them to look like, they may not have formal Charters, they might not have a website, but every country that I have worked in, including some of the most unstable in central Africa, has remarkable, empowered networks of women who are working to make their communities better.

JusticeInfo: I believe the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative has worked particularly on LRA-affected countries such as the Central African Republic and South Sudan. Can you say something about the involvement of women in peace processes there?

JK: I am glad you brought up South Sudan, because obviously it is a very timely and tragic case study. What I saw when I was travelling to Western Equatoria State (South Sudan) was that there was an extremely vibrant network of totally grassroots women’s organizations that had sprung up in the dearth of any other international engagement or NGO engagement. Women who had been abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army had formed small associations. With no budget, no grants and very little engagement from what we think of as the international community, they have organized to help heal themselves and build bridges to enable conflict resolution and conflict recovery. And what I think is most remarkable is the extent to which women’s organizations that had been formed to face the threat of the LRA were now pivoting to come together in the face of wider political instability in South Sudan.

I remember in particular the story of this incredible nun who had recognized the depth of trauma that children faced in LRA affected areas and she organized programmes completely on her own to have children connect with each other and connect with grown-ups and to feel that they were still loved, not stigmatized, and part of a social network. She also tried to organize a delegation of women to go to the governmental peace processes, and they were excluded by local male political leaders, even though their right to be there is codified in international law. You can see how sometimes women’s exclusion is played out on the ground, and we as an international community have to be there, have to be watchdogs and have to be aware that this kind of exclusion occurs. But it was really inspiring because this women’s group, even though they were kicked out and disallowed to participate physically, they went to a local print shop, printed dozens of pages of their manifesto and their commitment to peace and put flyers around the meetings in order to still have their voices heard.

JusticeInfo: In an interview with JusticeInfo last October, Congolese activist Julienne Lusenge complained that women had also been kicked out of peace talks in the eastern DRC. And she said the UN should make women’s participation in peace processes compulsory. Do you agree?

JK: I think the implementation is where we see the failure. They’ve already created the lofty aspirational language and then there hasn’t been a commitment to following it through. We have the lofty language, and I think what we need to do now is get the implementation right. Also peace processes are often very heterogeneous, brokered by different actors. It’s not always the UN that is a key player in them. So I would like to see other players like the European Union, the African Union and the United States also continue to renew their commitments to having women be full and engaged actors in peace processes. The UN is an extraordinarily important body, but it’s still just one piece of the puzzle.