Throughout Latin America a “post-transitional justice” trend is increasingly challenging the political bargains struck at the time of the democratic transitions in the region. This wave of late justice is clearly reflected in the rising number of human rights trials addressing past human rights abuses in several countries. South America’s regional giant, Brazil, has until quite recently, however, dodged this regional trend.

Brazilian Exceptionalism

Unlike other countries in South America, Brazil has not followed the pattern of challenging the military regime’s self-amnesty. Brazil’s Amnesty Law (1979) remains intact, upheld by the country’s highest court, the Supreme Federal Tribunal, in 2010. Brazil’s military rule ended in the mid-1980s, but it took until 2012 for the creation of an official truth commission. Although an extensive reparations programme for victims of the military regime has gradually grown under successive Brazilian governments since the mid-1990s, attempts to pursue prosecutions to address the military regime’s torture, murders, and disappearances, were resisted by the country’s judiciary.

Several factors explain Brazil’s transitional justice (TJ) exceptionalism. The military was in charge of the terms of the transition to civilian rule in the 1980s. Comparatively low levels of repression combined with memories of healthy economic growth during the military regime generated only limited political support for TJ among many sectors of the Brazilian population. Further, there are strong authoritarian enclaves in democratic Brazil and a revision of the military regime records is met with robust resistance from both the military and parts of the judiciary. The character of the Amnesty Law - as not a pure self-amnesty by the military regime but as a result of a broader campaign in favour of amnesty for political prisoners and exiles - limited the appeal for its revision. The relative salience of human rights violations of the past also tends to pale in significance to other (massive) human rights challenges in contemporary democratic Brazil.

Moreover, Brazilian politics are not conducive to TJ. The political party that might have been most strongly in favour of TJ, the Workers’ Party[1], has proved unenthusiastic, at best. Brazil’s coalitional presidential system makes policy and institutional reform prohibitively difficult and expensive, as the travails of the current government under President Dilma Rousseff make abundantly clear. In contrast to many other Latin American countries, Brazil has also been comparatively immune to international TJ pressures. In recent years, however, there have been dramatic—and generally unexpected—developments.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights and Gomes Lund

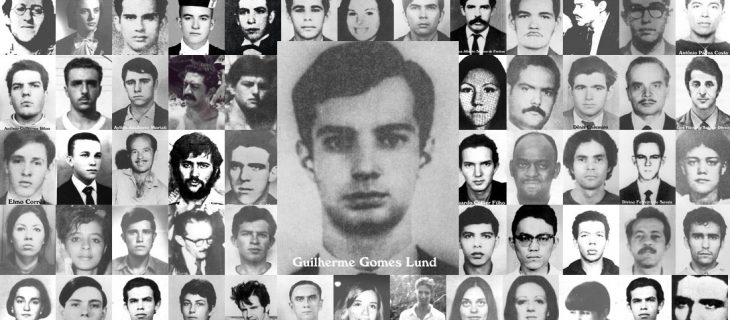

In particular, in 2010 the Inter-American Court of Human Rights finally issued its ruling in the long-running case of Gomes Lund vs. Brazil. The case is related to the military’s counterinsurgency campaign against Brazilian Communist Party militants, between April 1972 and January 1975, in the area of the Araguaia river banks in the northern state of Pará. Members of the group were detained and, after being identified, were killed and buried in secret. None of these deaths were acknowledged by the military.

In 1995, relatives of the disappeared members of the Araguaia guerilla submitted a petition against the Brazilian State to the Inter-American Commission. The case was named after Júlia Gomes Lund, whose son Guilherme Gomes Lund, a member of the Araguaia guerrilla, disappeared in 1973 when he was 26 years old. In November 2010, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found Brazil responsible for the forced disappearance of 62 people and ordered the investigation and prosecution of those responsible for these crimes. The Court challenged the Amnesty Law directly by ordering Brazil to remove all practical and judicial obstacles to investigating the crimes to establishing the truth as well as the responsibility of those involved.

More recently, the status of the Amnesty Law was challenged further by the report of the National Truth Commission, published in December 2014. The report documents systematic violations by the military regime, with extensive accounts of extrajudicial executions, arbitrary detentions, torture, sexual assaults and enforced disappearances. It stops short of an explicit call for the repeal of the Amnesty Law, but the report reiterates the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court in an implicit critique of the Supreme Federal Tribunal’s decision to uphold the Law. Although the work of the Truth Commission has been subject to fierce criticisms from across the political spectrum in Brazil, its report has the potential to provide an important catalyst for truth and accountability efforts.

Such impact can already be detected in the increasing number of investigations that have been opened by public prosecutors across the country. Brazil’s Prosecutor General publicly signalled a shift in the interpretation of the Amnesty Law, and he has repeatedly called on the Supreme Federal Tribunal to revise its interpretation of the Law. The relative strength of this growing momentum towards criminal prosecution remains to be seen. But these signals could potentially indicate a future circumvention of the Amnesty Law to pursue judicial accountability for crimes committed during the military regime. In other words, the most likely pathway to accountability, if any, would resemble the Chilean model (circumvention) rather than the Argentine model of accountability (overturning Amnesty laws).

Why Accountability for the Past Matters

Brazil’s ongoing tortuous path towards judicial accountability for the past highlights the importance of the passage of time in our thinking about TJ policy and practice. The ways in which any society deals with its past, present, and future tend to be intimately linked. It is precisely in this sense that TJ in Brazil is not exclusively about the past, or a form of backward-looking accountability. Rather, it is about the present and crucially directed towards the future. It raises issues of the government’s accountability towards its citizens and the limits placed on legitimate state violence.

The connections between past and present accountability deficits in Brazil are particularly apparent in the area of public security. Repression and lack of accountability continue to be the hallmark of security forces. Indeed, one of the main conclusions in the Truth Commission’s report is precisely the continuation of violations despite the significant political changes that Brazil has undergone since the country’s transition to democracy. But, beyond the lack of accountability for contemporary violations committed by individual police officers and commanders, a broader lack of political accountability exists. Political and economic elites in Brazil have, for decades, supported and legitimized repressive policing in ways that have undercut most attempts to reform its security forces.

Gomes Lund also highlights some of the continuing tensions in Brazilian civil-military relations. It is true that the military’s long-held opposition to a Truth Commission eased somewhat since the Supreme Court upheld the 1979 Amnesty Law in its ruling just a few months before the Inter-American Court’s judgement in Gomes Lund. Yet, the military resisted calls for cooperation with the Commission and it refused to comply with its legally mandated obligation to provide access to military archives. Therefore, by implementing the Inter-American Court ruling, the Brazilian government has the opportunity to further strengthen effective civilian control over military affairs.

One of the most important aspects of Gomes Lund is the affirmation of victims’ right to access information. The Brazilian government, the ruling states (§292), “is required to continue developing initiatives for the search, systematization, and publication of all information about the Araguaia guerrilla, along with information relating to human rights violations that occurred during the military regime, and guarantee access to this information.” The Gomes Lund ruling shaped legislative debates in Brazil that led to the implementation of a new Access to Information Law in May 2012. In short, complying with Gomes Lund could strengthen the very crucial cluster of rights regarding state accountability, transparency, freedom of information and the right to truth in Brazil. It shifts the responsibility to the state to provide public justifications for why files should remain classified.

The connections briefly illustrated above between human rights of the past, present, and the future are considerable. Much of the impetus behind efforts to establish and act upon these links comes from abroad: in particular, through the Inter-American Human Rights System in recent years. Clearly, in the current context of economic and political crisis, and in light of pervasive calls for a military coup from some sectors of the Brazilian population, memory struggles have become increasingly fraught in Brazil. But, it has also become increasingly urgent for Brazilian society to address its past. Simply put, the disappearances, torture and extra-judicial executions of Brazilian citizens highlighted by Gomes Lund are events of the past. Yet, it is up to the Brazilian government in the present to attempt to repair the harm done, ensure accountability, and, crucially, put in place preventive mechanisms and institutions that work to ensure that similar acts are not committed in the present and in the future.

[1] Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT)