JusticeInfo this week paid tribute to International Women’s Day with two stories reflecting women’s under-representation in transitional processes, a situation that is not only detrimental to women but also to reconciliation

“Despite women’s very low engagement in peace processes, we found that when women are substantively engaged in peace negotiations and conflict resolution, those processes are actually much more likely to be successful,” Jocelyn Kelly, director of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative Women in War programme, told JusticeInfo. “We now need to recognize that women’s issues as a whole are security issues, and that security issues are women’s issues.”

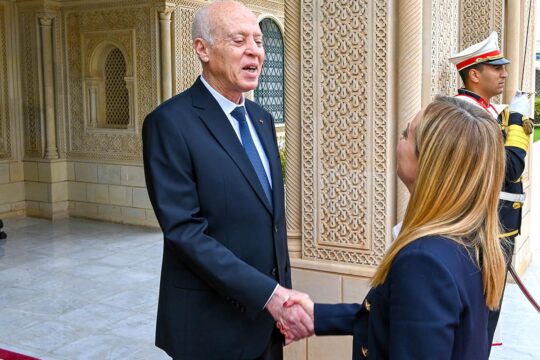

There is a similar view from Tunisia, where the Revolution’s promises have not been fulfilled and women seem to have been forgotten in the transition.

“Their history and identity, along with all the big and small battles they have fought, all go to make Tunisian women pasionarias of parity,” writes JusticeInfo correspondent Olfa Belhassine. And Tunisian sociologist and women’s activist Dorra Mahfoudh asks: “What is a revolution worth if it does not change prejudices, inequalities and attitudes?”The figures are cruel: “The number of women with diplomas who are unemployed is twice that for men,” writes our correspondent. “If a man and a woman go for the same post, the man usually gets it, even if the woman has brilliant qualifications.”

Sudan and South Sudan

Another flagrant transitional justice failure is Sudan. Its president Omar Al Bashir continues to travel without arrest, despite the fact that he has been under an ICC arrest warrant since 2009 for international crimes in Darfur that have left some 300,000 people dead. He was able to attend an Organization of Islamic Cooperation summit in Jakarta unperturbed. Indonesia is not a signatory to the Statute of Rome, the ICC’s founding treaty. In June 2015, as Bashir was attending an African Union summit in South Africa, a Pretoria court banned him from leaving the country pending a hearing on whether he should be arrested. But the South African government let him leave from a military airbase.

South Sudan, which became independent from Sudan in 2011 and is the newest UN member, remains the scene of a forgotten conflict that is murderous especially for women. "This is one of the most horrendous human rights situations in the world," UN rights chief Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein said in a statement. South Sudan has encouraged fighters to rape women in place of wages, while children have been burnt alive, the UN said in a report covering the period from October 2015 to January 2016.

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights demands the establishment of a hybrid court, in line with a failing August 2015 peace accord, to try those most responsible for the crimes committed since the beginning of the civil war in December 2013.

Brazil and Myanmar

In another part of the world, Brazil has been upholding impunity for 30 years after its return to democracy. “Unlike other countries in South America, Brazil has not followed the pattern of challenging the military regime’s self-amnesty,” writes Oxford Transitional Justice Research (OTJR) contributor Par Engstrom.

“Brazil’s Amnesty Law (1979) remains intact, upheld by the country’s highest court, the Supreme Federal Tribunal, in 2010. Brazil’s military rule ended in the mid-1980s, but it took until 2012 for the creation of an official truth commission.”

Same conclusion in Myanmar, according to another OJTR article on impunity for companies in the country. “Aung San Suu Kyi has already implied that she would accept leaving the past unaddressed,” writes Irene Pietropoli, who works in Myanmar for Amnesty International. “If retribution is far from the minds of the newly elected politicians, corporate legal accountability is even further away. They fear that exposing the accountability of the military and crony businesses for past violations may escalate existing tensions.”

A small consolation this week: Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos, in power for 39 years, has announced that he will quit power as planned in 2018… unlike some of his counterparts.