Twenty-four years ago, torn by different nationalist tendencies, Bosnia-Herzegovina plunged on April 6, 1992 into a sea of blood and violence. Sarajevo endured a terrible 44-month siege in which 10,000 civilians died, including 1,500 children. “Ethnic cleansing” became a terrible banality in the heart of Europe, and thousands of civilians suffered in horrendous camps reminiscent of the Second World War. One of the pyromaniacs of this violence from 1992 to 1995 was Radovan Karadzic, political leader of the Bosnian Serb Republic. He has been tried by the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia, and faces a possible life sentence for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

How to describe Radovan Karadzic? Like many other journalists, I saw him countless times in press conferences in Geneva, in palace lobbies or in his hotel room, where he sometimes gave interviews. He was both charismatic and at times clownish, with his crazy forelock. Wily and vengeful, playful and a liar, denying crimes despite the evidence and “obliged”, according to him, to stand up against “the creation of an Islamic republic in the heart of Europe”. Above all, he enjoyed his importance as the UN laid out the red carpet for him in Geneva so he would agree – once again, without effect – to let humanitarian convoys through to besieged and starving populations and promise that peace was at hand. He enjoyed seeing Western Europe, the United Nations and the ICRC almost on their knees, begging him for another agreement.

Addicted to the game, he raised the stakes when, in a mad hand of Poker, Bosnian Serb forces took 400 UN peacekeepers hostage at the end of May 1995, chaining them to strategic sites, using them as human shields to stop the UN raids. Hypnotized by the images shown again and again on television, Karadzic zapped from one channel to another for 24 hours watched by his friend the Lausanne publisher Dimitrievic, without realizing that this time he had gone too far in defying the big powers so openly.

Revenge was too sweet for this man born in June 1945, a month after the Second World War, whose Serb nationalist father had spent five years in the jails of Tito, considered a traitor by the Communists. Radovan the mediocre poet, lowly psychiatrist for a football club and doctor who got under-the-table payments for false certificates, managed between 1992 and 1995 to raise himself so high that he was calling the shots with Washington, London, Paris and Berlin.

Karadzic was not a cold and calculating cynic like Slobodan Milosevic, nor a Serb supremacist intellectual like his mentor, the ephemeral Yougoslav president Dobrica Cosic who propelled him into politics. He did not have the implacable savoir-faire in massacres of Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladic. As much out of opportunism as the patriotism of a devoted Serb, Radovan Karadzic became the Serb mascot. He gave himself body and soul to the ultranationalist cause, drawing on the political support of Milosevic, the ideology of Cosic and the military expertise of Mladic. He also added his own tune to the score, a mystical concept of Serb purity with its roots in rural life, which made him popular with the most radical nationalist fringes of the Serbian Orthodox church. When he was asked for his psychiatrist’s diagnosis on the state of his country, he said Bosnia had fallen victim to “a huge outbreak of unconsciousness, which was impossible to control”, but he placed its origin in the suffering of Serbs inflicted for centuries by the Turks, then the Germans in the Second World War and finally by the Communists.

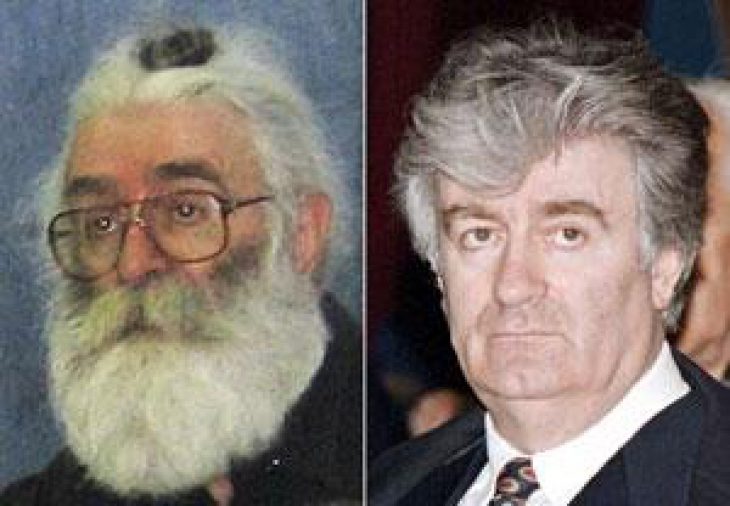

In 2008, after about a dozen years on the run, his arrest was almost burlesque, revealing once again the mystical side of the man: Radovan Karadzic no longer looked like the President of Republika Srpska, the braggart who strutted in Geneva and invited the Russian poet Limonov to shoot from the heights of besieged Sarajevo. He was hiding under the guise of an inoffensive 63-year-old alternative doctor named Dragan Dabic, hair pulled into a bun and running a weekly “meditation” column in a lifestyle magazine with advice on sexual problems and psychic disorders using a treatment based on “Human Quantum Energy”.

During his trial, despite the 400 witnesses who testified, Karadzic stubbornly maintained the same negationist line of defence, turning the aggressor into victim, claiming that no civilian was ever targeted, there was no “intentional bombardment of Sarajevo” or ethnic cleansing, and that the Srebrenica massacres were no doubt the work of his second-in-command, General Mladic. Victims’ families will still have to wait a long time for words of compassion or regret.

No doubt the worst aspect of Radovan Karadzic’s amazing path from poet psychiatrist to warlord was the mirror he held up to Europe. Despite outraged public opinion, Europe did not know how and did not have the will to intervene in a war taking place on its borders and killing tens of thousands of civilians, a precursor to the current Syrian tragedy. To cover its absence of policy and relieve its bad conscience, Europe offered humanitarian aid, peacekeepers to keep a non-existent peace and an international tribunal as an alibi for its failure to act. This tribunal has served to highlight the Law, leaving in the shadows the over-long inaction of a Europe torn by its own divisions.