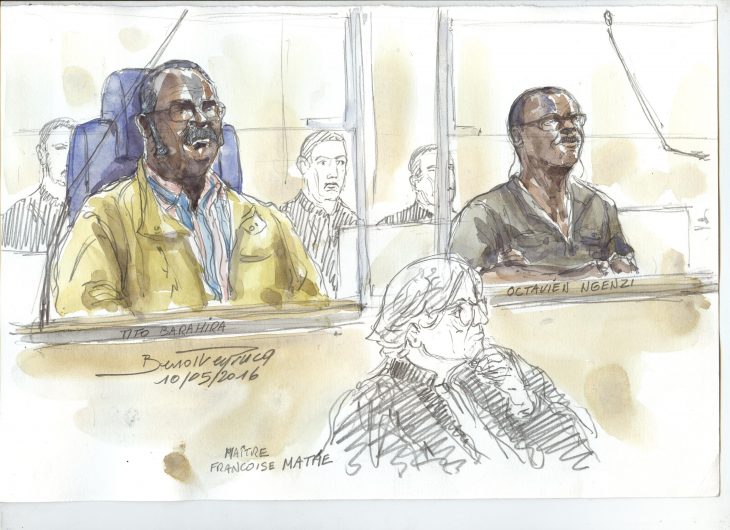

France this week started its second trial linked to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, with two Rwandan mayors in the dock. The two accused are former mayors of Kabarondo (eastern Rwanda), Tito Barahira and Octavien Ngenzi. They are both charged with genocide and crimes against humanity committed 22 years ago.

This trial, being held under the principle of universal jurisdiction, has been long awaited by Rwandan victims’ associations. It is led by France’s special crimes against humanity unit, created in Paris in 2012. The unit, which has received some 30 judicial complaints against Rwandans living in France, has thus belatedly opened its second trial. The first trial two years ago resulted in a 25-year sentence for former Rwandan intelligence officer Pascal Simbikangwa.

Rwandan genocide trials clearly remain difficult in France, whose role in the Rwandan genocide is controversial and still subject to military secrecy. Thus several incidents have marked the trial, even before it opened. For example, Judge Aurélia Devos, head of the investigating magistrates specialized in crimes against humanity at the Paris Court of First Instance (tribunal de grande instance) invoked a rarely used “conscience clause” to explain her resignation a month before the trial started. According to several sources close to the case, one of the factors was the link between Deputy Public Prosecutor Philippe Courroye and his personal advisor Jean-Yves Dupeux, who is a defence lawyer for other Rwandan genocide suspects.

The first week of hearings focused mainly on the personalities of the two accused and their past history. Franck Petit, JusticeInfo’s correspondent at the trial, thus described the questioning of one of the accused, Octavien Ngenzi: “His story continues, then becomes more precise when, `on May 6, 1986` he met a Nissan Patrol, `the car used by the intelligence services`. A man in the back announced to him that `the President of the Republic has just signed a decree appointing you mayor`. Ngenzi said he was surprised and a bit disappointed because he had other ambitions and didn’t want to be `just a mayor`. But it was impossible to refuse. Then again he fast-forwarded his story. `I held that post from May 7, 1986 to April 16, 1994,` he said. `Then I went to Kenya, the Comoros, and Mayotte. That’s how I came here.` Ngenzi then talked about the `mixed` population of Fleury-Mérogis, and stopped short, pulling the hem of his shirt. `I am feeling overwhelmed, I am sorry,` he told the court.”

In Rwanda, Sehene Ruvugiro, JusticeInfo’s correspondent in Kigali, tried to analyze how Rwanda’s approach to talking about the 1994 genocide has evolved. “For some time,” he writes, “the annual genocide commemorations have given more place to survivors who have managed to raise themselves up again than to the testimonies of trauma suffered. Instead of dwelling on the machete blows, nights hiding in the marshes, being hunted by dogs or hiding in holes under corpses, the survivors talk about small revenue-generating projects initiated after the genocide.”

This trend is much discussed in Rwanda. According to numerous psychiatrists it is a source of problems for the victims, who need to exorcize the massacres by telling what happened to them.

This same issue of “speaking out” also exists in Mali, which is just beginning a process of transitional justice. The specific role of women is a key issue. “Women not only have specific rights and needs,” former MP Dicko Fatoumata Dicko told JusticeInfo correspondent Bruno Djito Segbedji, “but also specific contributions to make to the process of pacifying and rebuilding the country. Recognizing the effects of the conflict, women are not content just trying to survive.”