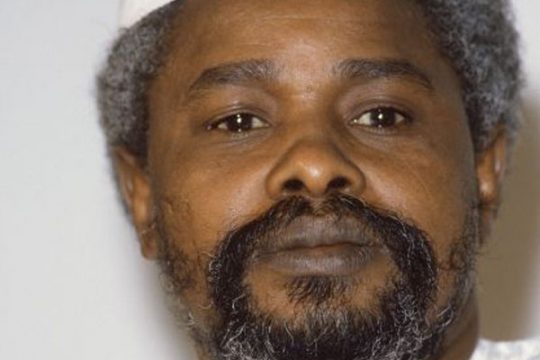

The successful prosecution of Chadian dictator Hissene Habre has galvanised the movement for a permanent forum for justice in Africa, but several legal roadblocks stand in the way, according to experts.

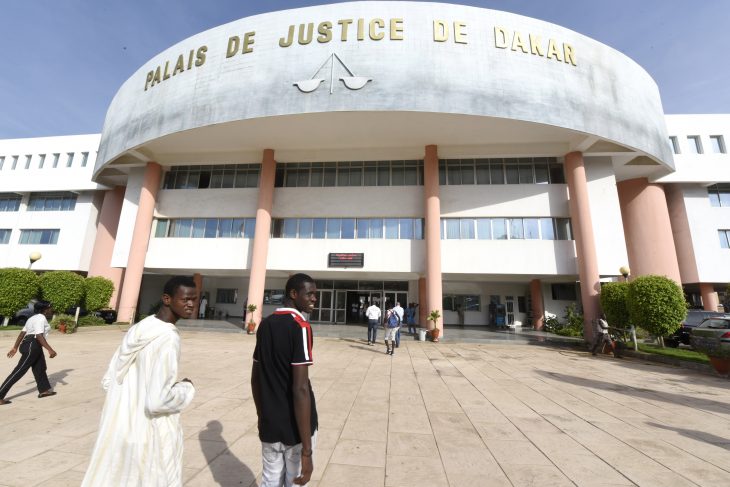

A special African Union-backed court in Senegal sentenced Habre to life in jail Monday for war crimes, crimes against humanity, rape, and sexual slavery, an unprecedented conviction that comes more than a quarter century after he left office.

The case also set a global precedent as the first time a country has prosecuted a former leader of another nation for rights abuses.

The verdict was "a vivid demonstration that the AU does not condone impunity and human rights violations," said African Union Commission chief Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma.

She said the judgement further "reinforces the AU's principle of African solutions to African problems."

Until Senegal's President Macky Sall was elected in 2012 and announced Habre would be tried there, the ex Chadian leader had lived in an upmarket Dakar suburb with his wife and children for more than 20 years.

The court that delivered the verdict -- the African Extraordinary Chambers (CAE in its French acronym) -- is to be dissolved after the case wraps up, and African rights groups would like to see a similar body set up with lasting jurisdiction over the continent.

"We want a permanent, continent-wide system for justice in Africa," Aboubacry Mbodj, secretary-general of Dakar-based African rights group RADDHO, told AFP.

"That's why -- after the African Chambers close -- we will continue to demand from the African Union a permanent mechanism so that heads of state are not above the law."

Senegalese Justice Minister Sidiki Kaba told journalists Tuesday that "foreign hands were not behind" the verdict, reinforcing the notion of the Habre trial being an all-African affair.

The AU has also "dragged its feet", RADDHO's Mbodj said, citing the adoption of the Malabo protocol in 2014, which envisaged an international criminal law section for the yet to be established African Court of Justice and Human Rights.

The protocol grants immunity to serving heads of state but also to "senior state officials", a vaguely worded element that Amnesty International has said "essentially promotes and strengthens the culture of impunity that is already entrenched in most African countries."

- ICC role -

Habre's prosecution is cited as an example of African best practice after years of criticism that the International Criminal Court (ICC), based in The Hague, has tried African leaders who critics say should be judged on the continent.

The AU, led in particular by Kenya, has accused the court of unfairly targeting Africans for prosecution as the majority of its cases come from Africa.

This included failed efforts to try Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, and his deputy William Ruto, for allegedly masterminding deadly post-election violence in 2007-2008 in which some 1,200 people died.

As some African states threaten to resign their membership of the ICC, its supporters on the continent say it still has an important -- and permanent -- role to play.

Ali Ouattara, president of the Ivorian branch of the Coalition for the ICC, which works to strengthen international co-operation between ICC member states, said the international court should act as a complement, given Africa's past weaknesses in bringing its own despots to book.

"We hope that Africa can judge Africans in a permanent way and we hope that the ICC will always be there, as a buttress," he said.

African failures to pursue their own criminal leaders meant the ICC was needed to act as a "policeman" on occasion, according to Ouattara.

"Just as any African citizen is a potential victim of our leaders, equally any head of state, any powerful person, is a potential target of the ICC or African jurisdictions," he said.

sst-cs/jom/jm/ccr

CAE