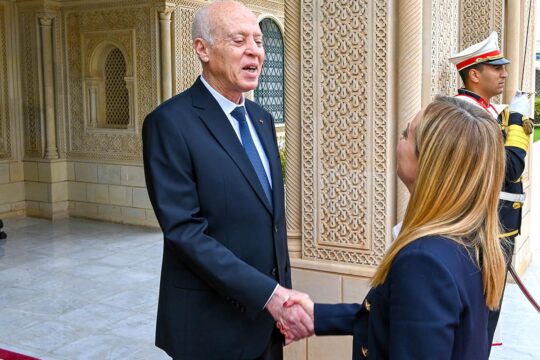

It was a calm week in transitional justice, but JusticeInfo.net continued to follow the chaotic transition in Tunisia with a look at corruption.

In an interview with JusticeInfo, anti-corruption magistrate Ahmed Souab explains that despite the promises of different governments, justice has not been delivered on cases concerning malpractice of the old regime. “I accuse the Tunisian justice system not of moving at a snail’s pace but of not having moved at all on these cases,” he says. “I also accuse the structures representing magistrates of failing to exert pressure to get these cases handled quickly and thus honour a slogan brandished by hundreds of judges in front of the Tunis Justice Palace on February 11, 2011: `down with the government’s justice and long live the justice of the people!` Finally, I accuse the media of not having investigated these cases.”

According to Ahmed Souab, the close aides and family of former dictator Ben Ali, especially his wife’s family the Trabelsis are back in force in the economy and the media “like a cancer that spreads to all parts of the body and weakens all its functions”. “Under Ben Ali, corruption was directed by government, now the practice has become `democratized`,” he says. “Parallel trade and industry are evaluated at more than 50% of the official economy of the country. The tentacles of corruption account for some 2% of GDP.”

Corruption is also a cancer in the world’s oil-rich newest country, South Sudan, which is still wracked by extreme violence targeting mainly civilians. “Central to this conflict is the looting of State coffers, looting of the resources of the State,” Brian Adeba of the US-based NGO Enough Project, who recently authored a report on South Sudan, told JusticeInfo in an interview. “President Salva Kiir himself has said that the country has lost some 4 billion dollars. Now where does this money go? This money is taken by the political elite and ferried out of the country, mostly to neighbouring countries, where it is stored and invested in banks.”

Brian Adeba also told JusticeInfo what he thinks the international community should do to tackle impunity in South Sudan. “The peace agreement is very clear that there is going to be a hybrid court to try perpetrators of these egregious crimes that are happening in South Sudan. I think it is very important to ensure that the peace agreement survives,” he said. “Not only should we ensure that it engages in reforming institutions of governance but that the hybrid court is set up to try these individuals. At the same time, the targeted sanctions we are calling for should not be focusing only on financial crimes but also leaders who have committed these egregious human rights abuses.”

On another continent, our partner Oxford Transitional Justice Research contributed an interesting analysis on Colombia, which is seeking reconciliation through the creation of a Truth Commission. “Colombia’s track record with investigative commissions suggests that a truth commission will struggle to create a coherent narrative of the violence,” writes the author, Jamie Rowen of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He notes that as of 2015, there have been twelve national investigations and three local investigations of the causes and consequences of the violence in Colombia, and everything is a source of disagreement: the date when the conflict started, the role of the government and the army, the position of the United States with regard to the drug traffickers who are also a product of the conflict and who are in their own way demanding reparations.

Of note also this week is a new contribution from our partner in the US, the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), looking at the new trial the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) wants to start against former Congolese militia leader Germain Katanga, who was recently released by the International Criminal Court (ICC). “This development represents not only a judicial novelty for the ICC but also a potentially important change of gear by the judicial system in the DRC,” write the ICTJ authors.

One might consider the ICTJ too optimistic in its view of the DRC’s and its President’s motivations, but the debate is open.