For the many critics of transitional justice, holding trials far from where the crimes were committed is a frequent subject of reproach. The International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands, is the epitome of this justice delivered abroad by a foreign court.

But the argument on international criminal justice versus local justice is not so simple. In an interview with JusticeInfo, Guy Mushiata, human rights coordinator for Swiss NGO Trial International in Bukavu (South Kivu), explains how justice is advancing slowly even in a country like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where it has often seemed forgotten. This is the case, he says, even for crimes that have been kept silent like violence against women. “On the one hand, civil society firmly and unanimously condemns sexual violence and hopes to see the victims destigmatized,” he says. “But on the other hand, judicial reality is different and judicial bodies still tend to practice uneven justice based on the rank and prestige of the suspected perpetrator.”

But, Mushiata adds, there has been progress in the recent Mutarule trial, in which soldiers are accused of involvement in an ethnic massacre. He puts this down to “a combination of three variables: the dynamism of the Mutarule victims’ community, the involvement of the central government and recurrent pressure from the international community”.

This shows how work on local justice and international pressure can work together.

The same issue is a concern in Colombia following the conclusion of a peace accord between the FARC and the government. ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda has called for the suspected perpetrators of the most serious crimes committed during Colombia’s 50-year war, which left more than 300,000 dead and disappeared, to be prosecuted. “The peace agreement acknowledges the central place of victims in the process and their legitimate aspirations for justice,” she said. “These aspirations must be fully addressed, including by ensuring that the perpetrators of serious crimes are genuinely brought to justice.”

Former ICC Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo opened a preliminary examination into the situation in Colombia as early as 2006, to determine if full ICC investigations were justified in the case that Colombian courts were unwilling or unable to try war crimes, crimes against humanity or crimes of genocide.

On the same theme, the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) has called on the ICC Prosecutor to “open with no further delay an investigation into crimes committed in Burundi since April 2015 that fall under the Court’s jurisdiction” and “make public statements on the progress of the preliminary examination opened on 25 March 2016 and on the conclusions of this examination”. In Burundi the local justice system, which is under the thumb of the regime, cannot prosecute independently. The FIDH also called on the African Union to act on South Sudan in accordance with an August 2015 peace accord, which allowed the setting up of a transitional national government. FIDH urged the AU to “support the prompt and effective establishment of the accountability mechanisms provided for in the Agreement”. This agreement provides notably for the creation of a hybrid court and a truth commission “in line with the standards of international human rights and criminal law”.

In Tunisia, often seen as a model in terms of transitional justice, reconciliation remains difficult especially when it comes to corruption and economic crimes committed under the former dictatorship. Chawki Tebib, known as “Mr Anti- Corruption”, told JusticeInfo in an interview that “the State today is infiltrated by the henchmen of the corruption barons”. The President of the nevertheless official National Anti-Corruption Body (INLUCC) added, however, that: “Today we have a fundamental asset, which is the awareness of people in Tunisia that corruption is something to be fought against. Tunisia is one of the rare countries to have made giant steps in its war on terrorism. I am sure that it can win the battle against corruption!”

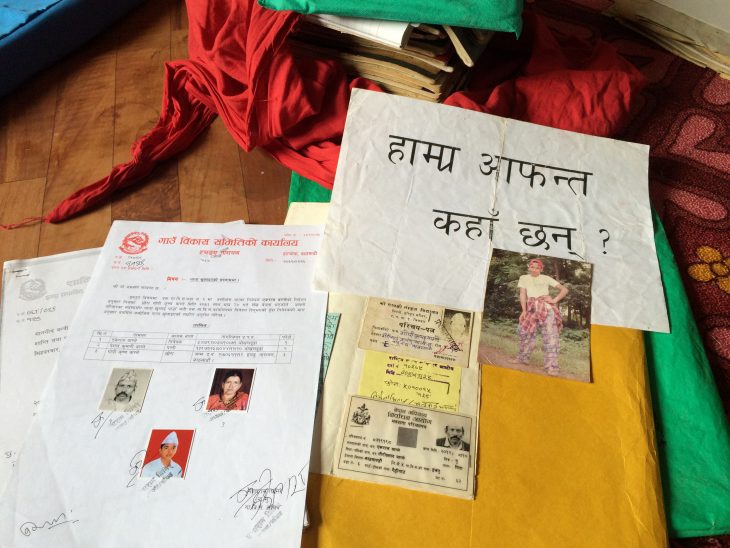

Finally, August 30 was the International Day of the Disappeared. We chose to focus on Nepal, a country where transitional justice processes remain very limited. More than 1,500 people disappeared in this country during the “people’s war” of 1996 to 2006, at the hands of the army, the police or Marxist guerillas. Since then, their relatives still have no news of their loved ones. No investigations nor Truth Commission worthy of that name have brought them justice or remembrance. “Who were they?” asks our correspondent, whose own father disappeared in 2001. “Why were they forcibly disappeared? Where are they now? Their relatives still wait for answers, living in a state of protracted ambiguity and anguish.”