The Gambia may be a small West African country that rarely hits the headlines, but this week’s announcement that it is pulling out of the International Criminal Court (ICC) confirms the malaise between the African continent and the Court in The Hague. After Burundi and South Africa, this decision raises fears of a new string of coordinated withdrawals that could become an epidemic as the ICC Assembly of States Parties (members) takes place in November.

This unexpected announcement by The Gambia is all the more spectacular because ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda is herself Gambian and a former Justice Minister under President Yahya Jammeh, who is far from a model in terms of respect for human rights and democracy. Speaking through its Information Minister Sheriff Bojang, the Gambian government accused the ICC of “persecuting Africans, particularly their leaders”. Up to now, The Gambia has backed the ICC and its most illustrious jurist.

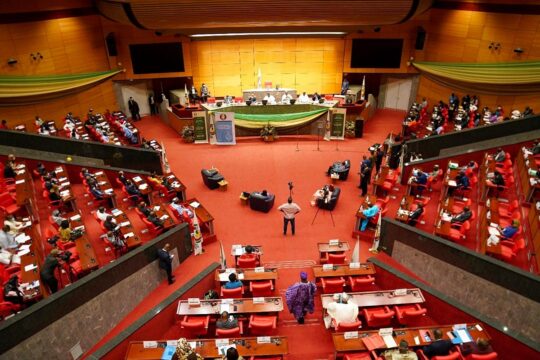

NGOs and human rights defenders immediately slammed this decision. “The announcement is a blow to millions of victims around the world,” said Netsanet Belay, Amnesty International’s Research and Advocacy Director for Africa. He rejected the statements of the Gambian minister that the Court was persecuting "people of colour", saying that on the contrary, "for many Africans the ICC presents the only avenue for justice for the crimes they have suffered”. Not all Africans agree with this condemnation of the Court. Several African lawyers defended the institution. Meeting in Arusha, the Tanzanian tourist town that is the seat of the African Court of Human and People’s Rights and former seat of the now-closed International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), members of the Africa Group for Justice and Accountability (AGJA) vowed to “encourage a positive and cooperative relationship between African states and the International Criminal Court”. They called on Burundi and South Africa to reconsider their decision. But as one of the participants who did not wish to be named told our special envoy Ephrem Rugiririza: “South Africa is a big power on the continent, a sort of driving force. There is the fear that it could pull in its wake other African countries among the thirty or so who have ratified the Rome Statute. There is certainly a counterweight in West Africa, made up of Nigeria and other countries in the region like Senegal. The campaign in favour of the ICC needs now to bring this support to its aid.”

These developments could signal a new round of violence in Africa, fed by impunity, writes Pierre Hazan, JusticeInfo’s editorial advisor. In his opinion, “all mechanisms to hold this back, however insufficient – like the ICC –, are necessary to limit the risk of new clashes and destabilization of the region”.

Still in Africa, Tunisia, which is a test ground for transitional justice, is preparing for the first hearings of victims before its Truth and Dignity Commission. But is Tunisia ready to listen to the victims, asks our correspondent Olfa Belhassine. She signals three possible risks: that witness testimonies be demonized and questioned; that the mass media ignore these hearings; and finally, that the names and responsibilities of those who led the repression be kept quiet.

Lastly, the Central African Republic appears to be further and further from a reconciliation process. A new wave of violence hit the capital Bangui as opponents of President Touadera and the UN mission (MINUSCA) organized a citywide shutdown. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon slammed these acts by “people whose goal is to destabilize the government and undermine prospects for peace and stability in the country” ahead of a November meeting of donor countries still ready to support a country that is divided and struggling to rebuild.