Last month’s presidential election capped four years of relative peace in Cote d’Ivoire. To make the West African country of 23 million an example of how to address a legacy of violent civil strife, newly reelected President Alassane Ouattara can now do more to acknowledge and account for past violence.

On the heels of a decade of north-south division and brutal post-election violence in 2010-2011 that left 3,000 people dead, Ouattara prioritized security and economic recovery during his first term. Thousands of former fighters were demobilized with United Nations support, while annual economic growth in the country, the world’s leading cocoa producer, topped eight percent.

The legacy of violent political and interethnic turmoil hangs heavy in Cote d’Ivoire. Politics in the country have long been characterized by hate speech, manipulation of youth groups to commit violence, and marginalization of whole sections of society. However, divisive rhetoric was thankfully in short supply during this year’s campaigns. Still, many Ivorians were quietly apprehensive ahead of the polls, and sporadic violence during a few demonstrations in September and October led to at least three deaths.

The October 25 presidential election – deemed credible and transparent by both Ivorian civil society and international observers – marked an important milestone in consolidating peace. Of course, as previous polls in Cote d’Ivoire and experiences elsewhere have shown, peaceful elections alone cannot guarantee a stable peace nor close the book on past grievances.

During a campaign centered on the economy and social issues, Ouattara also condemned impunity and committed not to interfere with the justice system’s efforts to prosecute those most responsible, on all sides, for the massacres, rapes, community destruction, and other abuses that were committed during the 2010-2011 post-election violence. In 2015, two newly created or revamped governmental bodies – the National Commission for the Reconciliation and Compensation of Victims (CONARIV) and the National Program for Social Cohesion – launched processes to identify victims of past violence and begin providing reparations.

Given this progress and Ouattara’s previously stated commitments to justice and victims’ rights, Ivorians have come to expect concrete results during Ouattara’s second term. In particular, the next administration should aim to speedily deliver on justice and reparations and promote fuller engagement on efforts to acknowledge the truth about Cote d’Ivoire’s past violence.

On justice, Ouattara must go beyond his commitment not to interfere with the judicial system, and take specific action to strengthen its impartiality and capacity to prosecute individuals for serious violations committed during the post-election violence. Those named to key Justice Ministry posts must also act impartially.

Ouattara should also ensure that the Justice Ministry’s special unit for post-election violence, known as the CSEI, has sufficient resources for the task. In addition, the Ouattara administration should give its full support for a draft law on witness protection now working its way through the National Assembly, which would enable more victims to testify and thereby bolster the credibility of the prosecutions and trials.

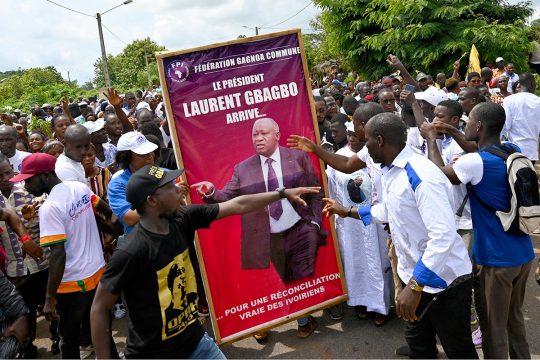

There is no doubt that serious progress on fair and balanced national prosecutions would help deliver justice for Ivorian victims of conflict-related abuses. The International Criminal Court (ICC) is due to begin its trial against former President Laurent Gbagbo and his co-defendant, Charles Blé Goudé, in January; while playing a very important role, the ICC alone cannot respond to the need for justice in conflict-related cases. Indeed, effective national prosecutions Cote d’Ivoire would be a critical way to show victims and society that the state is committed to guaranteeing human rights and the rule of law.

A far-reaching reparations process for victims, which had a solid start in 2015, must continue to make progress. The relevant governmental bodies should expand their outreach to victims’ groups and civil society to inform their policies and actions.

A newly created commission, CONARIV, made progress this year to finalize a victims’ list while making a solid effort to listen to victims and integrate their views. And the National Program on Social Cohesion began implementing financial compensations to victims in August, drawn from a US$16.7 million fund. But the work of these institutions has at times suffered from blurred roles and responsibilities and a lack of communication between the two, which President Ouattara should seek to improve by bringing both sides together to resolve their differences.

During his swearing-in ceremony on November 3, Ouattara proposed “new consultations with CONARIV” as part of further reconciliation efforts. While this is a positive step, the Ouattara administration must clarify as soon as possible how such consultations will be managed, and how they will complement previous and existing efforts to determine the truth about past conflicts and provide reparations to victims.

Last, Ouattara should use his office to promote further acknowledgement among all Ivorians about the country’s violent past. Official efforts to seek the truth about past conflicts stalled in the previous term. The work of the Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission culminated in a report in December 2014, which has yet to be made public.

Several Ivorian youth groups have made strides in acknowledging a painful past, with members apologizing for their role in the post-election violence of 2010-2011. Their brave and honest admissions should be followed by acknowledgement from the president and other political leaders, past and present, for the roles they themselves and their supporters played in the violence.

Serious, careful, and effective efforts to acknowledge Cote d’Ivoire’s past and account for grave abuses can strengthen the country’s economic and social progress. Ouattara’s campaign promised that, with him, Ivorians would “succeed together.” Pursuing truth and justice can help him make good on that promise.