The trial of Dominic Ongwen, a senior member of the notorious Lord’s Resistance Army, opens on Tuesday before the International Criminal Court in The Hague. Many horrors will be recounted, but the case also throws up deep ethical questions: is a child, brutalised and turned into a killer, fully responsible for his or her actions? If the abuses of government forces aren’t also being investigated, at what point does it become victor’s justice?

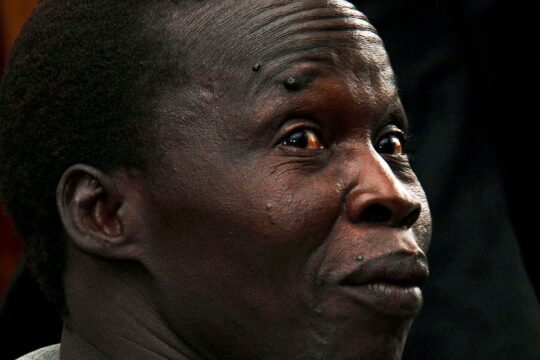

Abducted by the LRA at the age of 10, Ongwen became a protégé of rebel leader Joseph Kony and was forced to witness and carry out acts of extreme violence. He will be appearing before Trial Chamber IX to answer 70 charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. They include allegations of murder, rape, sexual slavery, torture, pillaging, and the conscription of children aged under 15 for combat.

It is the first time in the history of the ICC where the alleged perpetrator himself was a child soldier.

“I know it’s a delicate balance. It’s about accountability. It’s about whether Ongwen was responsible for the atrocities or not,” Herman von Hebel, the ICC registrar, told reporters on Monday in the Ugandan capital, Kampala.

Sympathy

In northern Uganda, epicentre of the two-decade-long insurgency, Ongwen is not uniformly thought of as a monster. Among many former LRA child soldiers, now back in their communities after amnesty and reconciliation programmes, there is sympathy.

Like Ongwen, they were forced to commit serious crimes, and some fault the government for not having protected them.

“He is a victim and not an abuser,” Thomas Otim, a former LRA combatant, told IRIN. “Ongwen, like many of us, had to obey and execute Kony’s orders. If he didn’t, he could have been killed…. He should be forgiven and pardoned.”

Even some LRA victims agree with Otim. Sarah Angee lost her parents and relatives in an LRA attack in her northern home district of Amuru.

“As a victim and survivor, I have accepted to forgive Ongwen for the atrocities and suffering he caused,” she told IRIN. “As a child soldier, he was conscripted and indoctrinated to kill, maim, rape women, mutilate, attack camps, abduct children, and other horrible atrocities.”

The LRA terrorised northern Uganda between 1987 and 2006. It emerged in the tumult of a divided Uganda, in which President Yoweri Museveni’s southern-based National Resistance Movement had fought its way to Kampala and overthrown the short-lived military rule of Tito Okello, an Acholi. Although the LRA was an Acholi-based movement, its victims were overwhelmingly from its own community.

In 2000, the government introduced a blanket amnesty for anyone who abandoned the group and renounced involvement in the war. Close to 30,000 took up the offer, but the government subsequently excluded the most senior commanders like Ongwen.

He is the only one of five indicted LRA figures to have surrendered, giving himself up in Central African Republic in January 2015. With the exception of Kony, the other three wanted men are believed to be dead.

Rather than the ICC’s retributive justice, Angee would like to see Ongwen pardoned and, like many of the ex-LRA who returned home, enrolled in a traditional Acholi reconciliation process known as Mato Oput.

“Let the ICC leave him to come back home and be given amnesty like other top LRA commanders. He will be cleansed and reconciled with the relatives and communities that he wronged and offended during the conflict through [our] local mechanism,” she said.

Meeting Ongwen

But Betty Oyell Bigombe, a senior director at the World Bank who – as a state minister for northern Uganda – worked for years to broker an end to the conflict, disagrees with the notion of pardoning Ongwen.

“I met Ongwen during the peace talks. He was the most hostile. I was very scared of him,” she told IRIN. “Ongwen can’t be left to get off scot-free. It’s true, Ongwen was abducted. It’s true, he was a victim. But, like so many others, he had an opportunity to defect. But he didn’t surrender for all those years. This raises a moral question. Why didn’t he?

“I am a stronger believer in forgiveness. But forgiveness has to have a limit. Forgiveness has to have reasons. Victims never really recover if justice is never there. It wouldn’t be good to see Ongwen in a suit driving a car and [the victims] have nothing,” she said.

“Whatever comes out of it [the trial] can be discussed,” she added. “[But] I also think this is important for the existence of the ICC. The ICC was created to protect the voiceless. It acts as deterrence so that any other person who has those intentions in future should know the consequences.”

Why mixed feelings?

Phil Clark, a Great Lakes expert at SOAS, University of London, believes victims' feelings toward Ongwen are mixed, and filtered through their own experiences.

“Many victims I have interviewed say they have children just like Ongwen – children who were abducted but who committed horrific atrocities, including back in their home communities. These victims therefore hate the crimes Ongwen has committed, but are sympathetic to him because of the way he was forced into the rebel ranks,” he told IRIN.

Lino Owora Ogora, a transitional justice and peace-building activist based in the main northern city of Gulu, agrees with Clark over the tangled emotions stirred by the case.

“The sentiments of victims towards forgiveness can also be explained by the fact that for a long time amnesty was promoted and embraced by the people as a means of ending the conflict,” he noted. “Because many commanders who surrendered before Ongwen were granted amnesty, the people feel he also deserves amnesty.”

“Yes, I think the government politicised and manipulated the ICC in the war against the LRA. The government used the ICC to isolate the LRA from the international community and to officially label the LRA a terrorist organisation,” said Ogora.

“How else can you explain the fact that today the same government that invited in the ICC in the first place is the same government that has turned into a bitter critic of the ICC, with President Museveni openly calling the ICC a 'bunch of useless people'?”

But Clark also faults the ICC. “As part of the pre-referral negotiations, the ICC prosecutor promised the government there would be no investigations of state actors as long as the government cooperated with the court. The Ugandan government was only too willing to cooperate. This meant the ICC would target the government's opponents such as the LRA while protecting the state from the threat of prosecution,” he said.

“In the eyes of affected communities in northern Uganda, this immediately delegitimises the ICC,” Clark suggested. “Local communities view both the LRA and the government as responsible for the atrocities they have suffered. Some communities even see government crimes as worse because the state – unlike rebels – is supposed to guarantee citizens' protection and security.”

Government crimes

Ongwen’s call to the dock on Tuesday has prompted fresh calls for investigations into alleged crimes committed by the army, the Ugandan People’s Defence Force, during the long counter-insurgency war in the north, in which human rights violations were committed.

“We need a full accounting for the atrocities, where both parties involved in the conflict have to account. The absence of accountability from the UPDF side will always remain an issue if not addressed,” said Joyce Freda Apio, a transitional justice expert.

“The heavy reliance by the Office of the Prosecutor on evidence gathered by Ugandan military intelligence raises concern if what is being pursued is the victor's justice,” she told IRIN.

Clark said that by ignoring government atrocities “for the sake of expediency”, the ICC had destroyed its reputation among the local communities.

“They see the court and the government as one and the same – and blame the court for protecting and even emboldening the state to continue committing crimes. For example, its violent crackdown against civilians in the three national elections held since the ICC intervened in Uganda.”

But Bigombe, the World Bank director and former state minister, sees that as disingenuous. “There have been complaints, but no organisation has communicated to [the] ICC and said, ‘Could you investigate UPDF as well?’ The ICC as an institution will not deal with outcries and rumours. If there was a letter or invitation to invite ICC to investigate the UPDF for their role in northern Uganda, I would be surprised if ICC turned their back.”

The Ugandan government referred the LRA case to the ICC in 2004 – alleged UPDF atrocities were not in the terms of reference. However, the government argues that it has always investigated allegations against its soldiers, and those found guilty have been punished harshly.

But there was also the government’s controversial strategy to force most of the population of the north into “protected villages”, a policy condemned by rights groups and local politicians.

Ongwen will enter a plea of guilty or not guilty to the charges being brought against him on Tuesday. The court will then adjourn to 16 January, when the prosecution will begin presenting its evidence. It’s a case Ugandans will follow with rapt attention.

A decade on from leaving Uganda, the LRA now numbers just a few hundred, operating in the remotest regions of the Congo, CAR and Sudan, but the legacy of the group’s violence still casts a long shadow over people’s lives.