The trial of Ugandan Dominic Ongwen, a former child soldier turned commander of the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), started at the International Criminal Court (ICC) on Tuesday December 6. Ongwen is accused of crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in northern Uganda between 2002 and 2005.

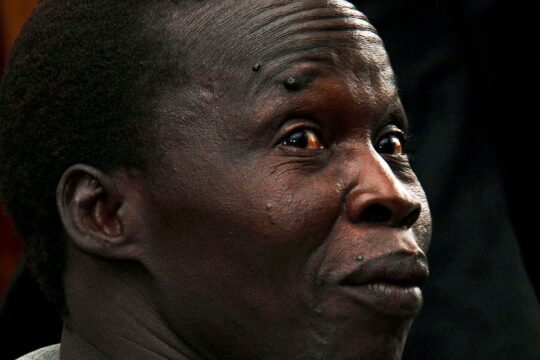

Seated in the box for the accused, Dominique Ongwen scribbled in the pages of his notebook as a court Registry official read out one by one the 70 charges against him. As the 58th one was read out, his lawyer Krispus Ayena Odongo rested his head against the back of his seat, whilst Ongwen studied carefully the few lines he had written. The day before, his lawyers had tried to get the case postponed, arguing that their client was not fit to follow the trial and did not understand the charges against him. But the judges saw this as a delaying tactic and rejected the request. The presiding judge also assured himself that Ongwen does understand the nature of the charges.

Standing to argue his own case, Ongwen rejected responsibility for LRA crimes. “It was the LRA that abducted children in northern Uganda,” he said. “It was the LRA that killed people in northern Uganda. It was the LRA that committed atrocities in northern Uganda.” And just to be more precise, he told the three judges that “the LRA is Joseph Kony, who is the leader”. Ongwen sees himself as a victim. But after being kidnapped by the LRA at 14, Ongwen became during 27 years of fighting one of its top commanders. He has pleaded not-guilty to the charges.

Victim or perpetrator?

The defence hopes to convince the judges by sowing doubt. But it was not really the portrait of a child soldier drawn by the Prosecutor. Fatou Bensouda nevertheless decided to tackle the victim-perpetrator issue head-on. It is also a subject of debate in Uganda, including for ex-child soldiers who surrendered and are still struggling to forget their past. Dominic Ongwen “was also a victim”, declared Bensouda. “He himself, therefore, must have gone through the trauma of separation from his family, brutalisation by his captors and initiation into the violence of the LRA.” According to one witness, whose words the Prosecutor quoted, “Dominic Ongwen was a good man, who would play and joke with the boys under his command and was loved by everyone”. But, continued the Prosecutor, it was the same witness who said she believed she was still too young to get pregnant, but had been raped by the accused. She still has the scars from beatings inflicted by Ongwen when she did not make his bed correctly. For Fatou Bensouda, what happened in Ongwen’s youth does not justify any of his crimes. And when other LRA fighters decided to surrender to the Ugandan army in return for amnesty, Ongwen decided to continue fighting.

A fierce fighter

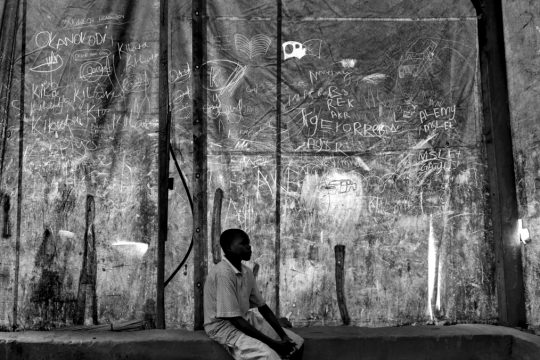

Ongwen rapidly became a fierce fighter within the LRA, a militia founded at the end of the 1980s to combat the new regime of Yoweri Museveni. Led by Joseph Kony, the LRA demanded a fair share of riches for long-abandoned northern Uganda, and based its demands on the biblical Ten Commandments. In 30 years of combat, first in northern Uganda and then, after peace talks failed, in the Central African Republic, South Sudan and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the LRA has killed more than 100,000 people and captured at least 30,000 children. Its methods are particularly cruel, as seen in a video shown by the prosecution during the hearing, in which children are seen being burned alive or disembowelled. According to the authorities, the LRA conducted more than 700 attacks between 2002 and 2004. The prosecution is to talk in detail about Ongwen’s alleged responsibility in four of these, against displaced people’s camps in Pajule, Lukodi, Odek and Abok. As head of the LRA’s Sinia brigade, Ongwen would tell his small soldiers to “kill everyone who is not one of us”. At his orders, they also looted homes and kidnapped women and children. The boys were subjected to rituals aimed at hardening them to the horrors of war. One had to watch his father’s body decomposing for three days. In combat, “if they didn’t run fast enough, they were beaten or killed”, the prosecution says.

Ongwen’s seven “wives”

As for the girls, Ongwen offered them to his soldiers as wives. The LRA’s rules are strict and do not allow sexual relations outside marriage. Commander Ongwen himself had at least seven “wives”, according to the prosecution. These women, young girls at the time, already testified behind closed doors in autumn 2015, and their testimonies have been added to the case file. Some fell pregnant after these forced marriages. The Prosecutor has identified 12 children born of these rapes, confirmed by DNA tests carried out by the Dutch forensics institute. These children are also victims, explained Bensouda, and carry the stigma of their parenting. Prosecuting attorney Benjamin Gumpert, who is leading the case, then talked in detail about the evidence. The first witnesses are expected to start testifying in January, he said. They include Ugandan intelligence agents who listened for ten years to LRA communications from Ugandan army barracks in the northern town of Gulu. The commanders, including Ongwen, reported their attacks to their boss Kony, who was most often in exile in South Sudan. Thanks to these interceptions, the Prosecutor hopes to show that Ongwen was a top commander. Three other LRA commanders, Odiambo, Vincent Otti and Lukwaya, were under ICC arrest warrants from 2005 but have now died. Only Kony is still on the run from the Prosecutor and armies of the region hunting him with the support of US advisors. The prosecution is also expected to call to the stand victims and insiders, including two of Ongwen’s former right-hand men.

Kidnapped at 14, arrested 27 years later in the northern Central African Republic and transferred to The Hague, Ongwen was said at first to be delighted with his new life in prison. But on the first day of his trial, this ex-child soldier and ex-commander of the LRA’s Sinia brigade said he felt as if he had “gone into the bush for the second time”.