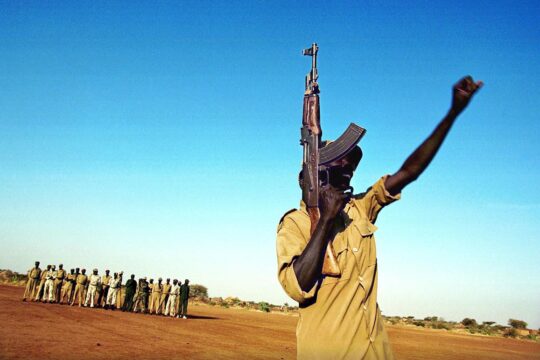

The Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide Adama Dieng has made various worrying statements this month of November. A few days ago, he has warned about the ethnic violence in the Central African Republic (CAR) and reminded the government its responsibility to protect. He has insisted on this responsibility when assessing the situation of Rohingya in Myanmar or of civilians in Iraq. On November 17th, he issued a statement on South Sudan, this time clearly stressing ‘a strong risk of violence escalating along ethnic lines, with the potential for genocide.’ Lately ‘the obligation [for the international community] to prevent ethnic cleansing’ has been raised by UN experts.

The NGO The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect (GCR2P) based in New York and recently in Geneva is constantly monitoring the Special adviser’s statements and publishes an atrocity alert. This NGO was established in 2008 with the goal to ‘promote universal acceptance and effective operational implementation of the norm of the "Responsibility to Protect" populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.’ It is funded by governments (Canada, Switzerland, France, Norway, etc.), foundations and individuals. But with increasing warnings about genocide and ethnic violence around the world, what is the impact of the norm R2P so far ? And in the case of South Sudan with a serious risk of genocide, is this concept really useful to avoid such a disastrous scenario ? Dominique Fraser, the Research Analyst of GCR2P in Geneva gives some answers to JusticeInfo.

JusticeInfo : Could you explain the concept of Responsibility to Protect ?

Dominique Fraser : The Responsibility to Protect is an important new international principle. It was adopted by UN member states in the World Summit Outcome Document in 2005 in the paragraphs 138 to 140. It refers to states’ obligations to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing collectively referred to as mass atrocity crimes.

The Responsibility to Protect has three pillars. The first pillar refers to each state’s responsibility to protect its population from the four crimes. The second pillar refers to the international community’s responsibility to encourage and assist states in meeting that responsibility. The third pillar refers to the international community’s responsibility to take timely and decisive action should a state manifestly fail to protect its population from one or more of the four mass atrocity crimes. Collective action must always be in accordance with the UN Charter.

The Responsibility to Protect has been invoked 50 times by the UN Security Council and over 20 times by the Human Rights Council.

JI : Both the armed interventions justified by the Responsibility to Protect and the International Criminal Court are criticized for discriminating between powerful and weak states. Does it mean that the concept of Responsibility to Protect needs to be rethought?

DF : The principle of Responsibility to Protect does not make a distinction between weak and strong states but on whether states uphold their responsibility to protect their populations from mass atrocities.

When the UN Security Council discusses a situation, it can become politicised, but that is not unique to the Responsibility to Protect: almost all international principles are currently under attack, including long-established norms such as human rights and international humanitarian law. Nonetheless, politicisation of the Responsibility to Protect should be avoided and civil society can play a role in monitoring situations and so contribute to de-politicising the Responsibility to Protect.

In Libya, the Security Council authorised the implementation of a no-fly zone to protect the population from the credible threats of mass atrocities made by Muammar al-Qaddafi. The use of force in Libya was authorised by the Security Council, condoned by the League of Arab states and carried out by NATO forces. It was an unfortunate but necessary step to protect the Libyan population and save lives. The international community should nonetheless have paid closer attention to the need to rebuild the country.

Other forms of military intervention taken in Libya however were not in keeping with UN Security Council Resolutions 1970 and 1973. Some states shipped arms to rebel forces despite the arms embargo that had been adopted under Resolution 1970.

Some interpretations of Resolution 1973, including those pertaining to regime change, also stretched interpretation of that Resolution to its limits. It is thus important for certain criteria to guide any instance where the use of force is authorised. The criteria include for instance the seriousness of harm and the use of force must be used at the last resort for the purpose of halting or averting the threat.

The Responsibility to Protect is much broader than the use of force and its main focus is the prevention of mass atrocities. Examples of where the Responsibility to Protect was invoked but the use of force was unnecessary include Kenya in 2007/8 and Guinea in 2009/10.

Dominique Fraser

JI : Does it mean that the change of regime in Libya was within the limits of the resolution ?

D. F : The debate whether regime change was beyond Resolution 1973 is still hotly debated. Scholars and practitioners tend to agree that NATO’s unequivocal support for the Libyan rebels was beyond the scope of the Resolution and it should instead have acted as an impartial actor once the immediate objective of the protection of civilians had been achieved. NATO actors, on the other hand, have continued to argue that the removal of Qaddafi was necessary in order to protect the population living in regime-controlled areas.

JI : Considering that today Libya is still facing an internal conflict, did this intervention result in the progress or the step back of the Responsibility to Protect ?

DF : The Responsibility to Protect has not suffered from the intervention in Libya as many observers have claimed. On the contrary: while the Security Council referred to the Responsibility to Protect in only a handful of cases in the six years between 2005 and 2011, since 2011 it has done so over forty times. The same is true for the Human Rights Council, which before 2011 referred to the Responsibility to Protect only once in 2008, but referred to it in an additional 20 instances in the past five years.

It is also important to measure the success of the Responsibility to Protect not solely in terms of the use of force, but whether it is able to shape states’ acceptance that they must protect their populations.

JI : You've mentioned Kenya and Guinea as countries where the armed intervention was unnecessary. Was it because the criteria were not met ?

D.F : In most cases, the use of force will not be necessary to achieve the objective of protecting populations from mass atrocities. In December 2007, disputed elections led to ethnically-fuelled killings in Kenya. It was in large part mediation efforts by the international community, led by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, which ended the bloodshed that had resulted in 1,133 deaths and hundreds of thousands of displaced persons. The mediation led to a power-sharing agreement and wide societal and political reforms (notably the police, the judiciary, and the media). It also ensured that the elections held in 2013 were largely peaceful and a political success. One shortcoming of the Kenyan case is the lack of criminal accountability for those most responsible for the violence in 2007/08.

JI : Regarding the situation of South Sudan, Adama Dieng has recently made a statement about the political conflict which seems to transform into an ethnic war. Yet his statement also highlights the inability for the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) to act in order to prevent the escalation of violence. Does it mean that the international community has its hands tied in South Sudan unless the transitional government of national unity takes concrete steps?

D.F : In South Sudan, it has become obvious that the transitional government is failing to protect its population from mass atrocities. The international community thus has a responsibility to take action.

UNMISS has encountered some issues, especially regarding the protection of civilians, including in UN protection sites specifically established to protect civilians from physical violence. A Special Investigation into the violence that took place in Juba in July this year concluded that key senior UNMISS personnel lacked strong leadership, which contributed to the mission’s inability to effectively protect civilians. It is important that the 4,000 troop-strong Regional Protection Force, proposed by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and authorised by the UN Security Council, be allowed to deploy as quickly as possible by the transitional government.

The African Union-led initiative to establish a Hybrid Court for South Sudan to address violations of international law must also be advanced. The Court would ensure that persons responsible for perpetrating crimes since December 2013 be held to account. Accountability for crimes is necessary to break the pervasive culture of impunity, which has fuelled recurring cycles of armed violence and mass atrocities in South Sudan.

The UN Security Council can and should also do more to protect the population of South Sudan. Earlier this month, the United States circulated a draft resolution in the Security Council to impose an arms embargo on South Sudan and widen the list of South Sudanese officials to be included for targeted sanctions. Such a resolution should be adopted immediately in order to stem the increasing attacks on civilians in South Sudan.

JI : Why does the government fail to protect its population in the case of South Sudan ? How do you explain it ?

D.F : I believe it's a matter of unwillingness. Despite the formation of the Transitional Government in April, both Machar and Kiir have portrayed a half-hearted willingness to implement the peace agreement of August 2015. There remains little incentive for political leaders to stop the ethnically-based killings and rapes that are perpetrated under the cover of political difference.

JI : Genocide is a process according to Mr Dieng. How would GCR2P describe the process to efficiently prevent it in this case? Could the failure of Responsibility to Protect in Darfur in 2004 force the international community to actively intervene in the near future ?

D.F : The warning signs for mass atrocities in South Sudan have long been present, including rising ethnic tensions and attacks. The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect has been calling for increased attention to the situation since January 2012.

Particularly worrisome are the increased use of hate speech and incitement to violence by government officials, which must end immediately. The physical protection of civilians must be prioritised by UNMISS and the Regional Protection Force upon its deployment. Accountability for crimes through the establishment of the Hybrid Court would also be a good step in breaking the cycle of impunity. It was planned to be adopted by the warring parties as part of the peace agreement of August 2015, but little progress has been made on this front since then.

These are important steps that would address the Special Adviser’s warning about the potential for genocide in South Sudan.

JI : Regarding the arms embargo in South Sudan, it has been mentioned for months now, why do you think it is still not implemented? What are the reactions of states when you as an organization suggest it ?

D. F : The U.S.’s proposal for an arms embargo is met with some resistance by member states of the UN Security Council. Some of them do not believe that an arms embargo will achieve the desired outcome as South Sudan is already awash with arms. This is not the position of the Global Centre, which urges all Security Council member states to immediately support the U.S. proposal to impose an arms embargo and widen the targeted sanctions list.

JI : You have recently opened an office in Geneva. What could be done with the UN here and particularly the Human Rights Council regarding the situation in South Sudan and more generally the situations that call for concern in other countries?

D.F : The Global Centre opened an office in Geneva in 2015 because we recognize that the Human Rights Council can and should play a role in the prevention of mass atrocities. Human rights violations often serve as an early warning sign for mass atrocities and the Council can thus act as an early warning mechanism.

The Human Rights Council could also call a special session to discuss the situation in South Sudan, which would highlight the seriousness of this pressing situation and demonstrate the Council’s commitment to the prevention of mass atrocities.

In anticipation of the recent Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of South Sudan, which took place on 7 November, the Global Centre sent out recommendations for UN member states to make to the transitional government of South Sudan. These recommendations were subsequently put forward by several member states, including the recommendations to prioritize the protection of civilians, UN staff and aid workers; to take immediate steps to establish the Hybrid Court; and to cooperate with the Commission of Inquiry. Member states also stressed the need for the rapid deployment of the Regional Protection Force.