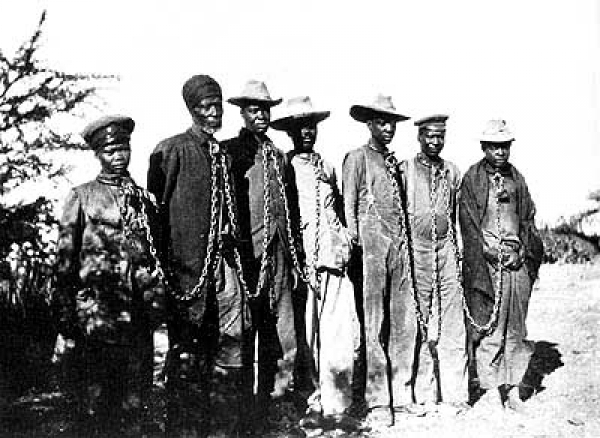

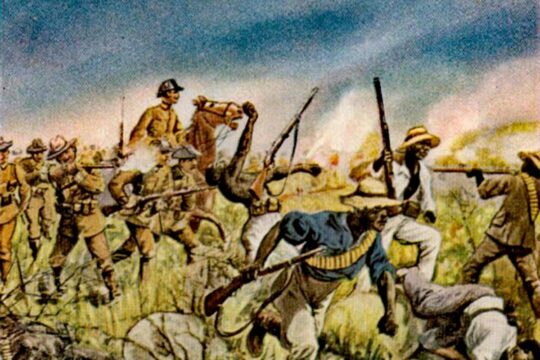

In this first week of the year, we were reminded of a “genocide” that has been largely forgotten, even if historians consider it the first such mass crime of the 20th century. This is the genocide of Hereros and Namas in Namibia between 1904 and 1908 by soldiers of the Second Reich when Namibia was a German colony.

While Germany has said it is ready to recognize its responsibility, descendants of the decimated Namibian communities concerned filed a class action suit before a court in New York demanding reparations.

The term genocide, which was officially recognized in 1948, did not exist at the beginning of the 20th century, but the troops commanded by Lotha von Trotha certainly massacred Herero and Nama communities, exterminating more than 80% of their people as part of a land grab in the name of “lebensraum” (vital space). Although long ignored, this first genocide has gradually been recognized as the precursor to mass crimes and concentration camps. Justice Info editorial adviser Pierre Hazan writes: “Some historians have made a link between the “Kaiser’s Holocaust” and the one committed by Hitler’s Germany, since both were driven by an ideology of eugenics and racial purity. The total impunity enjoyed by General Lotha von Trotha after committing mass crimes no doubt reassured the Nazis that they would not be punished for exterminating other populations.”

Class action

The class action suit filed in New York on Thursday by associations of the Herero and Nama people demands that their representatives participate in negotiations between Germany and Namibia. Berlin and Windhoek are currently negotiating a joint declaration in which Germany is ready to apologize for the massacres in its former African colony. But Berlin does not consider that it should pay reparations, since the crime of genocide did not exist in law in the early 20th century. The German government has nevertheless signalled that it could grant development aid to Namibia, a diplomatic manoeuvre aimed at satisfying Herero and Nama demands without setting a precedent with regard to mass crimes committed over a century ago.

The concept of genocide is also the theme of a recent book by Philippe Sands entitled “East-West Street” and subtitled “On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity”. This book, “which mixes individual stories and the dark chapter in world history from 1939-1945”, says Pierre Hazan, tells of the opposition and tension between two eminent jurists who deployed all their energy to put a legal classification on Nazi crimes and get the perpetrators punished: Rafael Lemkin, who invented the term genocide, and Hersch Lauterpacht, who got a new charge of crimes against humanity brought at the Nuremberg trials. For Lemkin, genocide was a key charge because it takes account of the Nazis’ intent to destroy a specific racial or religious group, whereas Lauterpacht thought it was “inapplicable” and even “dangerous” because it integrates into law the ideology of the perpetrators, which he calls “biological thinking”.

Ongoing debate

Today, “the difference in their positions appears dated given how much crimes against humanity and genocide are now part of the international justice landscape,” concludes Pierre Hazan. “But if formulated differently, the polemic remains: to what extent can the law restrain murderous intent? Should it be a weapon of denunciation at the risk of being merely rhetoric? At a time when Syria is burning and bleeding and international justice powerless, the issue remains.”

This week also showed another face of transitional justice with prosecutions for ill-gotten gains. France opened its first such trial in the case of Teodorin Obiang, son of the President of Equatorial Guinea and that country’s Vice-President. Obiang is accused by French magistrates of owning an immense fortune in France stolen from his country, which is one of the poorest in the world despite its rich oil reserves.

The investigations, opened after complaints filed by the Sherpa and Transparency International associations, have brought to light the considerable assets of Teodorin Obiang: a property worth some 107 million Euros on Avenue Foch, one of the smartest streets in Paris, and a collection of luxury cars (Porsche, Ferrari, Bentley, Bugatti).

This trial, which has been adjourned to June 19, sets a precedent in France where judicial authorities are also investigating the wealth held by families of other African leaders, including Denis Sassou Nguesso (Congo), the late Omar Bongo (Gabon) and former Central African Republic president François Bozizé, in France but also in the rest of the world, including Switzerland.