An Abidjan court’s March 28 acquittal of former Ivorian First Lady Simone Gbagbo, charged with “crimes against humanity”, was the big surprise of this week in transitional justice.

Was it a judicial or a political decision? Human rights defenders and associations representing victims of the fierce repression that followed the 2010 presidential elections in Côte d’Ivoire have criticized this decision. The Prosecutor had called for life imprisonment “in the name of national reconciliation”. Simone Gbagbo herself, who is already serving a 20-year sentence for “undermining State security”, boycotted this trial stained by errors and dysfunctions, according to independent observers and her lawyer, who whilst hailing this verdict denounced what he called biased justice. “We did not get the right to a fair trial,” said lawyer Ange Rodrigue Dadjé. “The Ivorian judicial authorities did not want to hear the players in the events cited.” The same criticism was heard from victims’ representatives such as Willy Neth, Vice-President of the Ivorian human rights league. “We had hoped that this trial would help reveal the truth about part of our past,” he said. “Nobody can deny that crimes were committed and that there were victims, but it is as if no-one was responsible, and we are disappointed.” Some 3,000 people were killed in Côte d’Ivoire between November 2010 and May 2011, according to the United Nations.

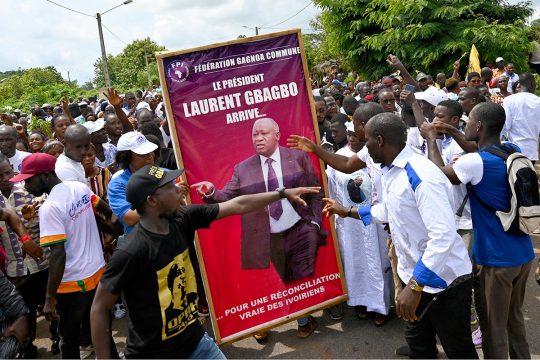

Even if there may be an appeal, this trial sums up the problems of transitional justice. Only people from the defeated camp have so far been put on trial under current President Alassane Ouattara, whose supporters also took part in the violence, leading to suspicions of government influence over the Ivorian courts. Also, the procedures in Côte d’Ivoire and the ongoing trial of Laurent Gbagbo, ex- President and husband of Simone, before the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, are being conducted without any cooperation.

Report on impunity

Universal jurisdiction, one of the pillars of international criminal justice is meanwhile making some headway, according to a cautiously optimistic report by several NGOs. The report, published by TRIAL International, in collaboration with Foundation Baltasar Garzón (FIBGAR), the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and REDRESS, shows that universal jurisdiction remains the fall-back mechanism to try perpetrators of international crimes (war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide).

“Despite constant attacks, universal jurisdiction continues to be a significant tool in the fight against impunity,” says Philip Grant, director of the Swiss NGO TRIAL International. “For victims, it is often the only way to justice.”

In 2016, forty-seven people suspected of crimes committed in another country were tried before national courts, according to the report. This marks slow but steady progress for the principle of universal jurisdiction.

Another disappointment for promoters of transitional justice is Myanmar, which is struggling to emerge from decades of dictatorship and where Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi is not in control of the army, accused of gross human rights abuses against ethnic minorities such as the Muslim Rohingyas. “I certainly think there is a striking lack of discussion on transitional justice,” Ashley South, professor at Chiang Mai University and an expert on ethnic politics in Myanmar, told JusticeInfo. “That is because of previous experiences in Myanmar, when around 1988-89 there was talk of holding the military to account and the transition was aborted by the military. There are certainly many traumatized individuals, families and communities who have suffered greatly. I am sure that among these diverse communities there is strong demand for justice.”

There are also limits on the possibilities that technology can offer transitional justice, notably hopes that satellite images can help track war crimes. “States, especially those with strong technological capacities, have understood perfectly the danger posed by these images taken from space, which respect no borders and could implicate fighters suspected of war crimes,” writes JusticeInfo editorial advisor Pierre Hazan. “They have therefore developed counter-strategies, using the same satellite technology and drones to manipulate information.” This is particularly the case of the Russians in Syria. “We have moved from having no images to having too many images,” concludes Hazan. “In the era of fake news and other `alternative realities`, this war over what happened has now been extended to the photos from space.”