People in Rwanda excommunicated from the Church because of their participation in the 1994 genocide are now being allowed back to Communion in some Catholic parishes. This rehabilitation, which would have been unthinkable only a few years ago, is part of a special programme of spiritual re-education. At first, however, the priests who initiated it faced a lot of opposition, including from some in their hierarchy.

Genocide survivor Claudette Mukamanzi, wearing a purple scarf that hardly hides the scar of a gash on her neck, has just embraced her “killer”, Jean-Claude Ntambara. “Ntambara,” she says, “I forgive you with all my heart, even if you killed me and decimated my loved ones!”

Twenty-three years ago she was “killed” and left for dead by the man she is now embracing in the new church of Nyamata, southeast of Kigali. “Renowned killer” Jean Claude Ntambara and some 100 other perpetrators kneel before the altar to make a final plea for forgiveness. The hands of their miraculously surviving victims are placed on their shoulders in a ceremony taking place just a few steps from the old Nyamata church, now a genocide memorial housing the remains of nearly 45,000 Tutsis killed there or nearby in 1994.

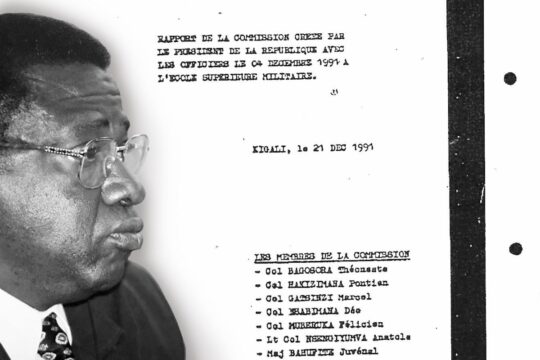

Father Emmanuel Nsengiyumva prays fervently for them all, both killers and victims: “Lord, chase from their hearts all ethnic discrimination, all hatred, all jealousy, all bitterness and all desire for vengeance […] Give them a new heart and spirit full of love and peace, and heal the hearts wounded by the unspeakable crime of genocide.” The priest sprinkles the perpetrators with holy water to cleanse them.

The ceremony ministered today by Father Nsengiyumva was first tried in the parishes of Mushaka and Nyamasheke, in southwest Rwanda. There, like in Nyamata, people convicted of participating in the genocide are automatically excommunicated from the Chruch. But they are given another chance once they have served their sentence, an intensive 6-week programme of contrition towards the Church and their victims. This programme has four parts. The first is on “human values, sin and its consequences”, the second on the “Ten Commandments of God”, the third on “the consequences for the victims and the perpetrators themselves”, and the last one focuses on “discrimination and its consequences”. At the end of the programme and after an evaluation, they may be readmitted to Communion and social relations with the families of their victims.

“We will all answer for our acts”

“But why excommunicate these people if they have served their sentences?” is a question asked by some people. “Because we are mistaken about the real state of reconciliation in Rwanda,” replies Father Eric Nzamwita, priest of Mushaka. “People pretend that they are living peacefully together, whereas in reality they avoid even crossing each other’s paths in the street.” Some genocide survivors such as François Safari denounce what they say are half-hearted confessions and repentance. He thinks the semi-traditional Gacaca [pronounced gatchatcha] courts which tried most of the genocide perpetrators were just a “disguised amnesty decided by the authorities”. “The criminals’ confessions were not wholehearted but were simply aimed at getting a reduced sentence,” he says.

Father Ubaldo Rugirangoga, the renowned initiator of this programme, likes to respond succinctly that “before God, each one of us will answer for our acts and not those of other people”. Did perpetrators tell the truth, the whole truth? Are they really sorry as they claim? Are the victims who say they have forgiven sincere? Only they themselves and God know. Human beings can only judge by observing people’s acts, explains Father Achille Nzamurambaho, priest of Ntendezi in southwest Rwanda. The National Unity and Reconciliation Commission, which welcomes this move by the Church, thinks that repentance and the carrying out of public interest work (TIG) are not enough for real reconciliation. “It is reconciliation with your own conscience and with the victims that brings real reconciliation and peace to the heart, more than pleading guilty,” says Fidèle Ndayisaba, executive secretary of the Commission.

Fear of telling the truth

The first steps in the community after serving a sentence are indeed very difficult, perhaps as difficult as prison. There is fear and anxiety at meeting victims, sleepless nights and nightmares, as Jean- Claude Ntambara and others testify.

“I was afraid of every survivor,” admits Anastase Habyarimana, “because I thought they would ask me questions about the genocide and the death of their loved ones.”

He has repented and says this reintegration programme by the Church has brought him relief, helped him overcome his fear and tell Antoinette Uzabakiriho the whole truth about the death of her mother. He told Antoinette how he killed her mother with a machete, how she struggled against death but finally died after being thrown into a pit. Antoinette says these confessions have finally brought her closure in grieving for her mother.

This initiative started in 2008 by Father Ubaldo Rugirangoga and which met strong opposition at the start, has proved its value across Rwanda. Other religious confessions are now interested in adopting it, according to Father Nzamurambaho, priest of Ntendezi, who was one of the first to follow Rugirangoga. Father Rugirangoga is now well known in all the Catholic parishes of Rwanda, where he is often invited to preach in the context of this new approach on repentance and forgiveness. Naphtal Ahishakiye, executive secretary of the main genocide survivors’ organization Ibuka says this new approach by the Church “has been taken up because of its results in terms of reconciliation”.