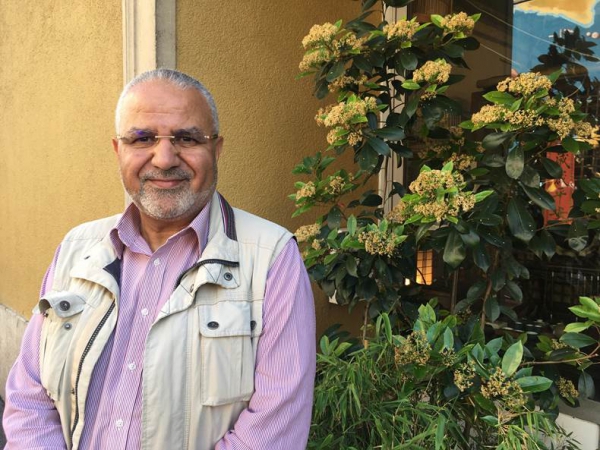

In 2004, Abdennacer Naït-Liman filed a complaint in Geneva to obtain reparations for torture suffered in the Tunisian Interior Ministry in 1992. However, it was in vain. Now the case of this Tunisian exiled in Switzerland is before the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), the highest court of appeal on the continent. Depending on the outcome, this case could open a new path for torture victims in countries of asylum.

“We are opening doors in the hope that victims of international crimes like torture and war crimes can have other recourse than criminal trials,” said Philip Grant, director of the NGO Trial International, a few days before leaving for the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. On Wednesday, lawyer Grant will be defending the cause of Abdennacer Naït-Liman, who obtained asylum in Switzerland in 1995 because of torture he suffered in Tunisia three years earlier.

In April 1992, this militant Islamist was living in Italy when he was arrested and handed to the Tunisian authorities. During his detention, Abdennacer Naït-Liman was tortured in the premises of the Interior Ministry of Tunisia, which was at the time ruled with an iron fist by Zine Ben Ali, the president overthrown in 2011.

Regaining dignity

“For 40 days, I was tortured day and night,” recounts Abdennacer Naït-Liman, 60, in an interview published by Trial International. “ My body was so hurt that I almost lost the use of a hand and a foot permanently. The inflicted pain was not just physical: they tried to break my spirit too, with threats, isolation and execution simulations.”

A first opportunity to get justice arose in 2001 when the Interior Minister of the time, Abdallah Kallel, came to hospital in Geneva for a heart problem. However Kallel, no doubt hearing that there was a complaint against him, managed to leave Switzerland before the police could catch up with him. But the man who created an association of torture victims in Tunisia was not about to give up.

A new legal avenue

His lawyers had found a new way of seeking justice through a civil procedure (less restrictive than a criminal one), under Article 3 of Swiss legislation on private international law.

“This law allows the complainant to determine which jurisdiction is competent to handle the case, and file a request for reparations in a civil court,” explains Philip Grant. “Article 3 of this law says that in the case that the complaint cannot be filed in the country concerned, which here would be Tunisia under Ben Ali, then Swiss jurisdiction may apply if there are sufficient links to Switzerland.”

According to Grant, “there are obvious links because he obtained asylum in Switzerland and received social benefits because of the torture he suffered, but this legal provision had never been used for a human rights violation”.

And so Swiss courts right up to the highest level (the Federal Tribunal) refused to take up the case, saying the links with Switzerland were not sufficient. “The judges did not take into account the implications of Switzerland’s ratification of the anti-torture Convention, and especially Article 14,” laments Philip Grant. According to him, Swiss reluctance to take up the case was out of fear of setting a precedent and being submerged by a large number of complaints. And he cites an argument put forward by the Swiss government in Strasbourg that “it is not our job to make Switzerland a place of legal jurisdiction for the whole of humanity”.

Taking the case to the European Court of Human Rights, Abdennacer Naït-Liman’s lawyers met similar reticence. But now the Court’s highest instance has finally agreed to examine the case, nearly eight years after it was referred.

The right to a trial in Switzerland

“Civil complaint, appeals before the Federal Tribunal, European Court of Human Rights. I knew the road would be long, but not so long,” says Abdennacer Naït-Liman in the same interview with Trial International. “So far, Switzerland did not consider it should take up my case because the tortures occurred in a third country. But where else could I seek justice than in the country that has offered me refuge from that abuse? Switzerland has recognized me as a victim but is preventing me from being anything else.”

The Grand Chamber of the ECHR will not decide on reparations, but rather whether Switzerland has violated Abdennacer Naït-Liman’s rights by refusing to hold a trial to decide whether the former Tunisian Interior Minister should pay reparations to his victim.

European significance

If the Court decision, expected in a few months, is in favour of the complainant, it could set a precedent for the whole of Europe. “The significance for Europe is to know whether torture victims who cannot claim justice in their country of origin could act in their host country to get reparations,” explains Grant. “That happens regularly in the United States. The European Court is seen as one of the most progressive bodies with regard to human rights. It could take inspiration from equivalent courts on the American and African continents and help generalize victims’ right to get reparations, by giving them access to civil justice. Because holding a criminal trial is never certain, and it takes time.”