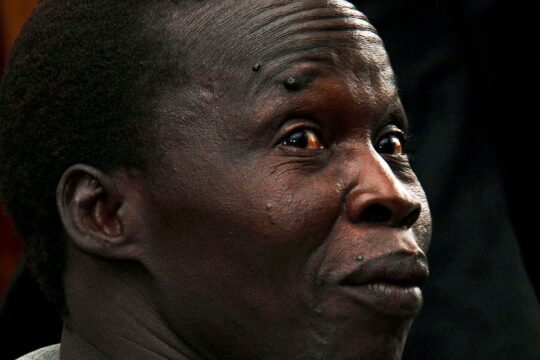

In a new report, Human Rights Watch argues that victims should have free choice of lawyer to represent them at the International Criminal Court (ICC). The report, published on August 29, is entitled "Who will stand for us? Victims' legal representatives at the ICC in the Ongwen case and beyond".

“Over time, the court has tended to give less weight to the views of victims when it comes to decisions about who will represent them before the ICC,“ says Human Rights Watch. In its report published on August 29, the human rights organization urges the judges and Registry to harmonize together the procedures and give victims more possibility to choose freely who will represent them. The report analyses in detail the procedure for designating lawyers in the Ongwen case and compares the situation with other cases before the Court. HRW stresses the disparities in procedures for choosing lawyers and in substance regrets that the Court does not give victims more opportunities to choose freely. Given the number of victims recorded in each case – 4,107 for the Ongwen case alone –, Court procedure provides for collective representation. Victims must therefore agree on a common lawyer for all of them. If this is impossible, it is up to the judges to decide. For Human Rights Watch (HRW), choosing a lawyer is a way for victims who are represented to develop a relation of trust with the person defending them. “The court’s system of victim participation, a key innovation in international criminal justice, creates a critical link between communities affected by atrocities and the courtroom,” it says.

4,107 victims and two lawyers

The researchers analysed in detail the process of designating lawyers in the Ongwen case. The judges accepted the participation of 4,107 victims in the trial of this former Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) commander. Over eight months, in 2016 and 2017, HRW interviewed 81 people, including numerous victims of the LRA militia, which was active in northern Uganda for more than 20 years. Dominic Ongwen was first accused of crimes against humanity committed in relation to an attack on a displaced people’s camp in Lukodi, northern Uganda. In January 2015, he was arrested and transferred to The Hague. In December, the Prosecutor added new charges against him for crimes committed in Pajule, Abok and Odek, and for sexual crimes committed within the Sinia brigade, of which he was the commander. Right from when the Prosecutor started investigating the crimes committed in northern Uganda, the victims of LRA crimes in Lukodi were made aware of how the Court works. “In Lukodi, victims were really well organized by NGOs,” explains Michael Adams, a researcher for Human Rights Watch. But this was not the case for the sites of the other crimes of which he was later accused. In Odek, the victims were interviewed individually. In Pajule, they were simply not consulted, and so the judges decided for them. In Abok, the victims took part in meetings together and chose their lawyer. But ICC officials tried to influence their choice, explaining that lawyers working for the Court would be better able to represent them, says Human Rights Watch. In the end, the Court did not fully follow the victims’ proposals, deeming that in certain cases the process of selecting private lawyers had not been transparent, and adding that constraints of budget and time prevented the procedure being continued. In the end, more than 2,600 victims are therefore represented by two lawyers, Fransisco Cox and Joseph Akwenyu Manoba. For the other victims, the judges designated Paolina Massidda from the Office of Public Counsel for the Victims (OPCV), a body which is part of the ICC Registry. In its report, Human Rights Watch refrains from comment on the differences between lawyers employed by the Court, like those of the OPCV, and those practising privately. Several testimonies nevertheless show that victims feel better if they are represented by lawyers closer to them, who come from their region and know their stories. One of the witnesses interviewed by HRW thus explains that the lawyer was chosen “because he was close to us”. In a public meeting, several lawyers were proposed to the victims. “Names of lawyers were brought in a book,” says the witness. “We heard the lawyer and chose him. I saw the trial on the screening. I was pleased to see him deliberate in the Court because he is a good man.”

Creating trust between victims and the Court

“The fact that victims can participate in ICC trials can help ensure they feel that justice has been done,” says Michael Adams of Human Rights Watch. The NGO regrets the absence of clarity with regard to certain stages of the procedure, notably when the judges have deemed that it was impossible to agree a common choice of council. “We don’t say the Court necessarily did something wrong in the Ongwen case,” Adams told JusticeInfo in a phone interview. “What we say is that Ongwen gives an opportunity to rethink its approach to the victims, make sure that they create the opportunity for victims to choose.”

“The ICC’s rules may not give victims an absolute right to counsel of their choice, but they do protect that choice to a significant degree,” he continues. “The court needs better policies to more clearly justify when it steps in to take away that choice.” The Human Rights Watch researcher also adds that the judges should “focus on understanding what’s happening in the local community, so as to “permit the local community, at the earliest point, to be ready and able to choose their own way… and if they are ready and able, to engage with them in a way that supports them”.

Human Rights Watch deems that it is up to the judges to evaluate on a case by case basis the time needed to choose a lawyer. At a time when the Court is thinking of reforming its legal aid system, it warns that the rights of victims should not be undermined for budgetary reasons. “Tight budgets at the ICC are forcing decisions that undermine the court’s connection with victims and risk weakening the court’s legitimacy,” stresses Michael Adams.