In a report published on February 5, human rights organizations express concern for the situation of victims of the summer 2008 Russia-Georgia war. Two years after the International Criminal Court (ICC) opened an investigation, they are calling on the Court to go faster. In The Hague, the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) asserts that the investigation is “progressing at full speed”.

The 50-page report calls for the world not to forget victims of the lightning summer 2008 war (August 7-12, 2008) that pitted Russia against Georgia for the separatist province of South Ossetia. It is published by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the Georgian Human Rights Centre (HRIDC).

“Almost ten years have passed since the conflict and victims feel today that they are not being heard,” explains Delphine Carlens of the FIDH. At the end of 2015, several thousand victims expressed opinions in favour of ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s request to open an investigation. On January 27, 2016, the judges gave it a green light. But since then, no arrest warrants have been issued.

“The investigation will take as long as needed to gather the required evidence, taking into account resource, security, and cooperation factors,” explains the OTP, saying that it is nevertheless progressing fast and that its staff are frequently in the field in Georgia and elsewhere. In 2015, the Georgian authorities informed the Prosecutor that they had stopped their own investigations because of lack of access to South Ossetia and lack cooperation from Russia, which is what led Bensouda to open an ICC investigation. But does the ICC have more scope than Tbilissi? This question has been a delicate one from the start. Russia has not ratified the ICC treaty. It cooperated with The Hague for a while on the death of Russian soldiers in the conflict, but on November 16, 2016, Russian President Vladimir Putin withdrew Moscow’s signature from the Treaty of Rome [the ICC’s founding treaty]. This symbolic decision came a few days after the Prosecutor in one of her reports spoke of the Russian “occupation” of Crimea. “Cooperation from the Georgian Government is forthcoming,” says the OTP. “Unfortunately, and despite best efforts, engagement with the Russian Federation and with South Ossetia has so far proven to be difficult.” But, it says, “investigative activities continue nevertheless”. “This is not a unique situation,” it continues, “and the OTP has successfully addressed such difficulties in other investigations in the past.”

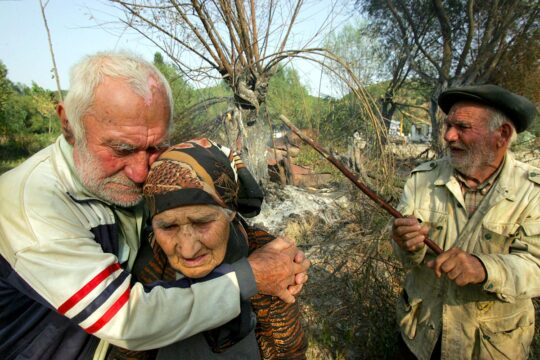

Elderly people in damaged homes

The two human rights organizations are nevertheless concerned about the outcome. “Victim narratives illustrate that they have suffered from crimes such as murder, forcible displacement, destruction of property and pillage, and continue to suffer nowadays,” they say. “However, if the OTP deems this case not to be prosecutable on the basis of the evidence available, this must be communicated to victims as soon as possible.” Hoping to convince the Prosecutor to speed up investigations, they stress the gravity of the crimes committed and their impact on victims’ lives today. In 2016, the HRIDC met 34 victims from ten villages near Gori and in the Berbuki displaced people’s camp. The report describes a neglected population, mostly elderly people who refused to flee during the war, some of whom are living in partly destroyed homes with plastic-covered windows, suffering hunger, lack of health care and medicines, stress and mental problems.

In their report, the FIDH and HRIDC say it is likely that “should the Georgia investigation proceed to trial at the ICC, many of these crime-based witnesses may have difficulty recalling the details of the events that took place given that the events took place almost 10 years ago”. Will these witnesses, elderly and traumatized, be able to testify one day before the ICC? “It is incumbent upon the OTP to act swiftly in order to ensure that victims are able to participate and see justice in their lifetimes,” say the two organizations.

Others stated that they continue to live in fear of being kidnapped by South Ossetian authorities or the Russian army, the report says, “given that the ABL [administrative border between South Ossetia and the rest of Georgia] shifts every so often, encroaching further and further into Georgian territory”, with one NGO stating that “you can fall asleep in Georgia and wake up in South Ossetia.”

The report describes the case of one inhabitant whose house straddles Ossetia and Georgia. People who cross the demarcation line, not always marked, are often arrested, fined or jailed, sometimes for weeks. According to the Georgian authorities, 327 people were arrested in this way in 2016. “The prospects of reconciliation between ethnic Georgians and South Ossetians living close to the ABL appear unlikely as there is little opportunity for these communities to interact and air grievances,” say the two organizations. As tensions persist between Moscow and Tbilissi, this is all the more the case. In late January 2018, the Russian parliament ratified an accord creating a joint military force with the separatist territory of South Ossetia, whose “independence” has been recognized by Moscow.

Lack of ICC outreach

The NGOs’ other concern is the fact that the ICC is little known in Georgia. In 2016 it got a budget to open an office in Tbilissi, but the Registry kept postponing its opening (see our interview with Nika Jeiranashvili of Open Society). The ICC finally signed a cooperation agreement in July 2017 and opened offices on the ground in January 2018. But this lost time has meant that some people in Georgia are not even aware of the existence of the ICC, which they sometimes confuse with the European Court of Human Rights, say the NGOs. In the absence of an awareness campaign, the Deputy Justice Minister went himself to the Gori and Kareli displaced people’s camps in May 2017 to explain the ICC’s mandate. But, as the report rightly explains, “the Georgian authorities are also under investigation for the potential role that they played in the 2008 hostilities”. Outreach with affected communities should therefore come from “a more neutral source, such as civil society, and optimally the ICC outreach section”, they conclude.