Context - Khmer Rouge terror: Cambodia has been scarred by decades of violence and war, beginning even before its independence from France in 1953. During the Cold War era and the Vietnam War (1955-75), the regime of Norodom Sihanouk (1953-1970) tried a balancing act between the US and the Communist powers in North Vietnam, China and the Soviet Union. In 1970 Sihanouk was driven from power in a coup by his army chief-of staff Lon Nol, who enjoyed US backing. Sihanouk fled to China and set up a national liberation front that included Khmer Rouge Communist guerillas. Cambodian civilians suffered heavily in the civil war that followed Lon Nol’s coup, and as a result of US bombing against North Vietnamese bases in Cambodia.

Nevertheless, the worst chapter in Cambodia’s history was undoubtedly under the ultra-Maoist Khmer Rouge (KR) regime. The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, took the capital Phnom Penh in April 1975, unseating Lon Nol. Between 1975 and 1979, the KR installed a reign of terror that left at least 1.7 million people dead (UN figure) out of some 7.5 million people at the time. The KR had planned to create a form of agrarian socialism which was founded on the ideals of Stalinism and Maoism. Its policies of forced relocation of the population from urban centres, torture, mass executions and use of forced labour led to the deaths of an estimated 25 percent of the total population.

Political ideology was a large part of the Khmer Rouge motivation. But it also targeted various ethnic groups, forcibly relocating minority groups, and banned the use of minority languages. Religion was banned, and the repression of adherents of Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism was extensive. According to historians, one of the fiercest campaigns was directed at the ethnic Cham Muslim minority. The exact numbers of Cham people killed are unknown.

The KR’s attempt at the purification of Cambodian society along racial, social and political lines led to the purge of military and political leaders of the former regime, purges of industry, journalists, students, doctors, lawyers and intellectuals, as well as Vietnamese ethnic groups. It also conducted purges within its own ranks. Those who were not tortured in KR jails and concentration camps died as a result of forced labour, starvation and deprivation of medical treatment for treatable diseases.

The KR reign of terror ended with the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1979. Pol Pot and Khmer Rouge forces fled to the border region with Thailand. Up to 20,000 mass graves, known as the Killing Fields, have been uncovered. Under the tutelage of Vietnam, many of Cambodia’s new leaders were former KR who had fled the movement and taken refuge in Vietnam. These included Hun Sen, who became Prime Minister in 1985 at the age of 34.

The Khmer Rouge, from its bases near the Thai border, continued to destabilize the country for two decades, as guerrilla warfare continued. In 1991, a peace deal was signed in Paris. A UN transitional authority shared power temporarily with representatives of the various factions in Cambodia. In 1993, elections saw the royalist Funcinpec party win the most seats, followed by Hun Sen’s Cambodian People's Party (CPP). Hun Sen refused to step down and threatened to secede. As a result, a coalition was formed with Funcinpec's Prince Norodom Ranariddh and Hun Sen as co-Prime Ministers. The monarchy was restored, with Norodom Sihanouk becoming king again.

In the mid-1990s, thousands of Khmer Rouge guerrillas surrendered in a government amnesty. Pol Pot died in his jungle hideout in 1998. The last senior KR leader to resist, former KR military commander Ta Mok (“Brother Number Five”), was captured in March 1999, bringing the civil war to an end. He died in a military hospital in July 2006

In 1997, Hun Sen forced Ranariddh out of power by military force. In 1998 he was again elected Prime Minister and remains in that post to this day. In January 2015, he marked 30 years in power. The Hun Sen government is criticized for massive corruption and land grabbing, and clamping down on opposition, including the press and human rights activists.

Cambodia has been extremely slow to prosecute serious crimes committed during the KR terror. The first trial before a UN-backed special tribunal (see below) began 30 years after the crimes were committed. Most senior KR leaders are now dead, and those that survive are aged and infirm.

Transitional Justice Mechanisms

UN-backed special court: In 2003, the UN and the government of Cambodia concluded a lengthy negotiating process and agreed to create the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) to try senior Khmer Rouge leaders. The ECCC is a hybrid court within the Cambodian justice system. It consists of Cambodian and international judges, prosecutors, defence teams and administrative support, and is supported by the UN and international donors.

The ECCC has a mandate to try serious violations of Cambodian penal law and international humanitarian law committed between April 17, 1975 and January 6, 1979. This includes genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Victim participation is one of its defining features.

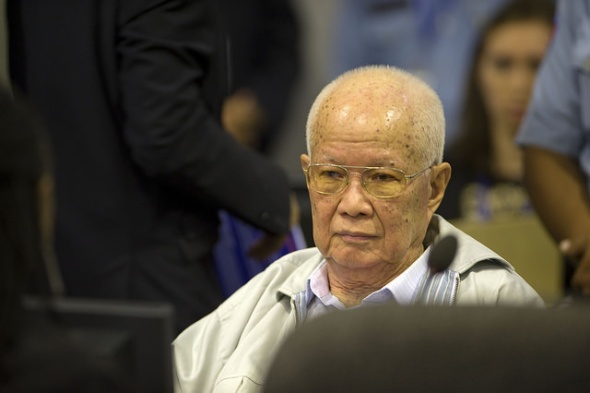

The court was slow to get off the ground. It has been criticized for alleged corruption and political interference. Nevertheless, it started operations in 2006 and has so far convicted three people: Kaing Guek Eav (“Duch”), who ran the notorious Khmer Rouge S-21 torture prison where more than 12,000 people died; Nuon Chea (“Brother Number Two”), who was Pol Pot’s second-in command; and Khieu Samphan, who was the KR head of state. Two others were indicted: KR foreign minister Ieng Sary, who died in March 2013 while on trial; and Ieng Thirith, Sary’s widow and former KR minister, who was released by the court in 2012 with proceedings suspended on medical grounds (severe case of Alzheimer’s).

Five other individuals are being investigated. Progress on their cases has been slow, amid warnings from Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen against the prosecution of additional suspects of the previous regime. However, on March 3, 2015, International Co-Investigating Judge Mark Harmon charged former KR navy chief Meas Muth and Im Chaem, a female former KR district commander, in absentia with homicide and crimes against humanity. Muth was also charged with war crimes. On March 27, Harmon also charged former KR official Ao An (also known as Ta An) with crimes including crimes against humanity. Internationally appointed judge Harmon issued the charge, but his Cambodian counterpart You Bunleng did not support his motion. Cambodian judges outnumber their international counterparts on the tribunal and can vote down a move to formally indict the suspects at a later stage. The suspects now have access to their case files through their lawyers and can participate in the investigation, according to the Court.

In its first judgment in July 2010, the ECCC found Duch guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced him to 35 years in jail, which was reduced by five years for a period of illegal detention prior to his trial. Although Duch pleaded guilty, he said he believed he should not have been tried because he was not one of the most senior leaders. He appealed the judgment, but his appeal was overturned in February 2012 and his sentence was increased to life imprisonment.

In August 2014, the court sentenced Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, the two most senior surviving KR leaders, to life in prison for crimes against humanity. Their appeals are pending. They both face a separate trial for genocide and other crimes against humanity in the same court.