What effects of the Trump government attack against the ICC?

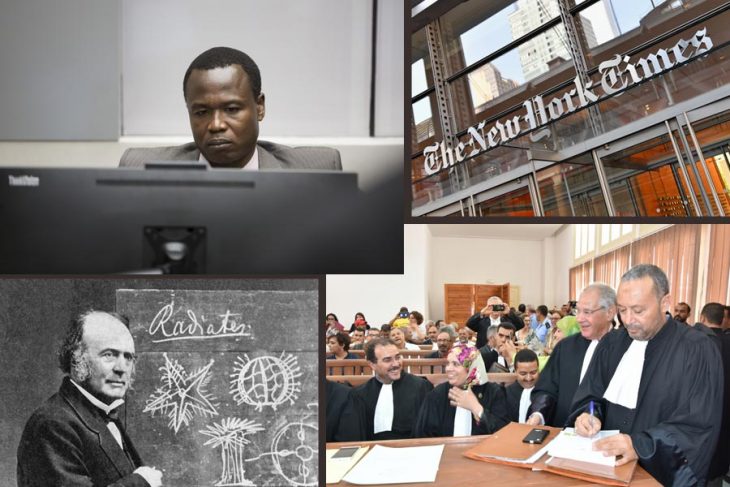

US security advisor John Bolton’s September 10 attack on the International Criminal Court (ICC) continues to make news. In an Op Ed for the New York Times of September 17, JusticeInfo editor Thierry Cruvellier analyses what is behind this new offensive by Washington. What is the reasoning of the Trump administration? To what extent can the ICC really scare the US, notably on the Afghanistan case, where the ICC Prosecutor announced a year ago that she has opened an investigation that could target members of the US army or the CIA? Does the Bolton initiative show the weaknesses of the US more than the uncertain impact of the court in The Hague? What are the risks for the ICC? Paradoxically the court, which is contested by some of its own members and has lacked support for years, could rally more supporters thanks to this American hostility.

Dominic Ongwen, the ICC’s imperfect poster child

Dominic Ongwen’s defence team started presenting its case before the ICC on September 18. Ongwen is the only one of the five Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) leaders indicted by the ICC who is in the dock. However, he has a unique story, the story of a child soldier conscripted forcibly who is now being tried for war crimes after surrendering himself in 2015. He is also the lowest ranked of the five, and probably the last one alive apart from LRA leader Joseph Kony. So he is both victim and perpetrator, something the defence will make central in its arguments. Although the evidence against Ongwen is considered solid, the ICC Prosecutor has stressed in other cases that “child soldiers are traumatized by default, just by being child soldiers”, University of Amsterdam assistant professor Thijs Bouwknegt says. Ongwen’s mental health and Kony’s “spiritualism” will also be central to the debates as defence witnesses, including Ongwen’s wives, take the stand in coming weeks.

Suspects absent from Tunisia trials

In Tunisia, trials before specialized criminal chambers are due to resume on September 21. A Lawyers without Borders report based on observation of the nine trials already held stresses the absence of suspects and isolation of the judges, who lack political support in a context of growing influence in government of members of the former regime.

For the upcoming trials, most of the specialized chambers have decided to call again the accused and witnesses who have not yet presented themselves. But for many of the suspected perpetrators, the current climate favourable to impunity and returning former members of the elite to power encourages them to boycott these courts.

Concerns about the process have also been increased by a move to transfer most of the judges, which directly threatens the proper functioning of the trials. It was the Association of Tunisian Magistrates (AMT) that sounded the alarm. In a press conference on September 5, the association expressed concern about the transfer of almost all the judges of the specialized criminal chambers as part of the 2018-19 judicial plan of the High Council of Magistrates (CSM). The only chamber that has escaped these judicial staff changes is that of Nabeul, which on September 21 started the second hearing in the trial related to Chammakhi, an Islamic activist tortured to death under the Ben Ali regime.

As the trials restarted, an exhibition called “Voices of Memory” opened in Tunis on September 22, based on the stories of eight Tunisian women including victims of the dictatorship and human rights activists. All these women have the conviction that art and story-telling can help anchor in history the painful memories that are not yet part of a calm public debate. The interactive exhibition tells how important during the years of oppression was the koffa, the basket that families sent to loved ones held political prisoner by the Ben Ali regime. The koffa, object of desire in a bare prison space and a message of love, is now inspiring Tunisian artists.

For Khadija Salah, a former political activist long harassed by police, “Voices of Memory” is group therapy. “We have moved from being victims, to being mistresses of our own destiny,” she says. “Even if in the beginning we all cried, we ended up laughing and taking some distance from the suffering of the past.”

Revising the past: A Swiss response to a global issue

To what extent should we take down statues, change the names of streets, towns and mountains when they bear the names of people who contributed to human misery? The spectacular removal in Charlottesville, US, of a statue of General Lee, a pro-slavery hero of the American South, is far from the only case. The debate is ongoing in several countries. But Switzerland has found its own, very Swiss response.

Louis Agassiz was long a respected personality in the country. Born in canton Fribourg in 1807, he emigrated to the United States and was one of the fathers of the natural sciences in the 19th century. His reputation might have remained intact if Swiss historian Hans Fässler had not in 2007 shed light on the openly racist theories of the scientist, who called Africans a “degenerate race”, opposed mixed marriages and offered scientific support for the so-called Jim Crow laws which institutionalized anti-black racism in the southern United States.

At the beginning of September, the University of Neuchâtel renamed the Espace Louis-Agassiz. It is now named after Tilo Frey, one of the first women MPs in Switzerland whose mother was Cameroonian and who was a pioneer of women’s and minority rights. But other representations of the scientist remain. The merit of this typically Swiss compromise is that it does not wipe out the memory of Louis Agassiz, but recognizes in him both his qualities as a great scientist and the strength of the prejudices that inhabited him. What is important, writes JusticeInfo editorial advisor Pierre Hazan, is not to eradicate the past but to learn from it. But he thinks the Swiss compromise cannot necessarily be applied elsewhere, because “finding a balance between remembrance and eradication, between glorification and contextualization is all the more difficult in societies where symbols serve as identity markers for the battles of today”.