International tribunals usually have a shelf life; they are expected to wrap up their work by a specific date, and so it falls to a successor institution to tidy up loose ends. In the cases of the former United Nations Tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, their institution, officially titled the UN International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals and known by its acronym the MICT, deals with what’s left over, such as whether a prisoner gets early release and following up on any fugitives still at large.

One of those outstanding matters is the appeals cases of Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadzic and his military commander Ratko Mladic who were respectively found guilty of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes and sentenced to 40 years for Karadzic while Mladic got a life sentence.

A nasty squabble between the MICT’s own judges was precipitated by a defence motion in the Mladic case calling for the disqualification of three judges on the appeals panel including the MICT’s own president Theodor Meron.

Tit for tat between old judges

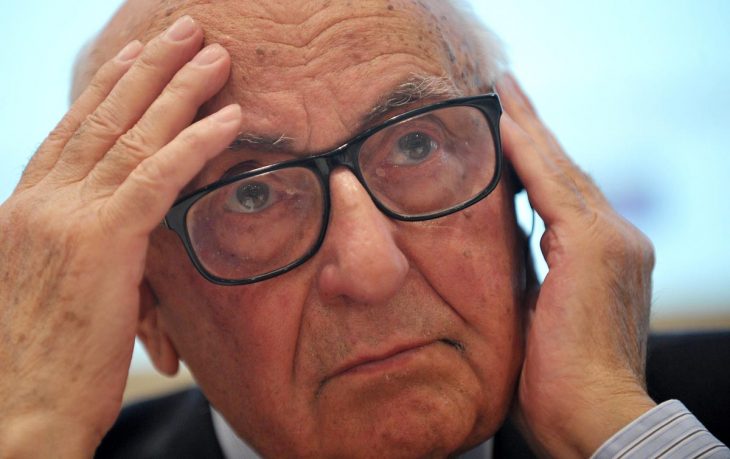

Because Meron, 88, was himself implicated in the request he assigned the decision to the other most senior judge available: Jean Claude Antonetti, 76. Antonetti disqualified all three judges because they had sat on cases which had found some of the Serb commander’s subordinates guilty of crimes and thus could have an appearance of bias.

The defence team for Radovan Karadzic, unsurprisingly, followed suit on the same grounds. Meron not only agreed to step down from the Karadzic bench but he also blasted the Antonetti Mladic ruling for suggesting that judges could be biased, saying it “clearly contradicts established jurisprudence” and “harms the interests” of the MICT.

These decisions sparked a slew of tit for tat motions between judges Antonetti and Meron which ended with Meron issuing an order to have a five-judge panel look at the question of whether Meron could recuse himself and appoint another judge. But Antonetti is already planning to rule on a second defence motion directly asking him to disqualify Meron.

Observers of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) will know that Antonetti comes with substantial baggage. He was the main judge in the trial of Serbian ultra-nationalist Vojislav Seselj. Seselj, known for his incendiary speeches during and after the 1990s Balkan wars, was at first acquitted in a widely condemned ruling that flaunted decades of ICTY jurisprudence to find there was “no evidence of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population of Croatia and Bosnia Hercegovina” during the wars. In that case he also issued a nearly 500-page concurring opinion on the ruling essentially agreeing with himself. On appeal, many of Antonetti’s findings were overturned and Seselj was convicted to ten years in prison.

The Prosecutor wants a Judge disqualified

At the MICT the office of the prosecutor has now waded into the fray and filed its own motion to disqualify Antonetti from the Karadzic proceedings. The prosecution contends that Antonetti is the biased one and has already shown he does not consider himself bound by precedent. Experts say this is the first time prosecutors at an international criminal court or tribunal has sought the disqualification of a judge. “This development is unprecedented in several ways and shows the abnormality of the situation,” Sergey Vasiliev, assistant professor of international criminal law at Leiden University, tweeted last week.

Since its establishment the ICTY has fought an uphill battle against allegations of bias and doubts about its legitimacy from nearly all sides in the Balkans region. Whenever a former foe is convicted the court has been praised but when a group’s own heroes are found guilty judges are accused of anti-(fill in ethic affiliation of accused) bias.

On the international stage the Mladic and Karadzic appeals proceedings may seem like an afterthought but in the region they are still followed closely. A survey done in Serbia in December 2017 as the ICTY officially closed found great distrust in the tribunal. Fifty-six percent of respondents find the ICTY to be partial and biased. In contrast only 6 percent believed it was entirely impartial. In fact of those respondents who considered themselves well informed about war crimes cases 76 percent felt the court was biased.

A boon for nationalists

The fact that the institution’s own judges are debating who among them is the more biased will reinforce the court’s opponents and sow doubts in the many more moderate thinkers who have heard regular accusations from their political leaders that the court is intrinsically biased.

Serb nationalist newspapers have already gleefully reported on what they are calling ‘the war between judges’, said Radosa Milutinovic, a Serbian journalist who has followed the tribunal closely since 2002.

“This row between Meron and Antonetti does not help the tribunal’s reputation; it shows the judges can be petty and vain and fight over control,” he told JusticeInfo.

And the MICT can’t win: A ruling which favours Meron will be seen as confirmation of institutional bias. And if fellow judges follow Antonetti’s arguments they would essentially back his new test for disqualification of judges – that they ruled on cases of military subordinates – which undermines the legitimacy of the many cases already adjudicated by the ICTY where this bias test was not applied. Whether the appeals chamber in the Karadzic case sides with Antonetti or Meron is ultimately irrelevant, much of the damage is already done.

“There is an old saying that the Balkan produces more history than it can digest. It feels to me like the tribunal is doing the same,” said Milutinovic.