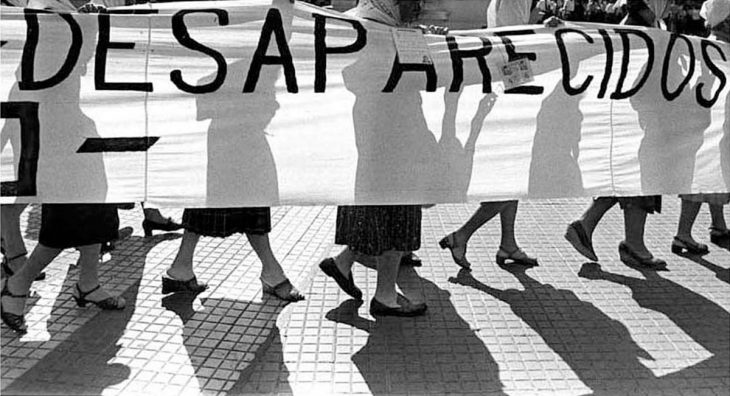

Chilean exile and poet Ariel Dorfman wrote about a woman whose husband disappeared at the hands of the state. Every year a man asks her hand in marriage, and every year she replies: ‘No, thank you very much, I appreciate your concern, but I am not a widow, so stay away from me, don’t ask me for anything, I won’t marry you, I am not a widow, I am not a widow, yet’. Such cases are the focus of this post.

This post enquires on the alleged necessary relation between knowledge of truth about serious human rights violations and the capacity to exercise rights and obligations of those seeking that truth. Scholars refer to this capacity in terms of juridical personality — subjects of rights and duties are endowed with juridical personality. I focus on the case law of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on two grounds. First, forced disappearances and the right to truth have received unparalleled recognition in it. Second, Article 3 of the American Convention on Human Rights states that every human being has a right to juridical personality and prescribes the non-derogable rule that everyone must be recognised as a person before the law.

When states refuse to disclose the truth about forced disappearances and fail to investigate, acknowledge responsibility or apologise, the capacity of relatives of desaparecidos to be recognised as persons before the law is seriously hindered. I focus on the latter arguing they cannot fully exercise their rights and duties if they do not know what happened to their beloved.

The recognition that individuals have a right to truth, and that failure to disclose it causes severe suffering for those seeking it, is part of the Court’s jurisprudence constante. The Court has held that refusing to disclose the truth to relatives of a disappeared may trigger a violation of their right to a humane treatment, access to justice and information. Yet the Court does not generally rule on whether a breach of the right to truth violates the disappeared’s family right to juridical personality. One exception is the case of desaparecidos’ children given in adoption at time of birth. Their right to juridical personality has been declared violated since the state denied truth about their real identity, causing breaches of identity rights and hereditary rights.

The relation between the right to truth and the right to juridical personality might not be at the centre of Inter-American jurisprudence. Against such limited appreciation, I defend an interpretation of the Convention based on the ‘pro persona’ principle of legal reasoning. This principle holds the interests of individuals at its heart and prescribes an interpretation of the law that best achieves the protection of individuals.

Are desaparecidos subjects of rights and duties?

Subjects of rights and duties are legally entitled to rights and duties and capable of exercising them in practice. Nevertheless, in the 2000 case Bámaca Velásquez v Guatemala the Court took a restrictive interpretation of Article 3, refusing to consider that forced disappearances violate the right of disappeared persons to juridical personality. A defence of the Court’s position is found in the Opinion of Judge Ramírez that draws attention to the difference between the de jure capacity to be subject of rights and duties, and the de facto possibility to exercise them. He argues that Article 3 is violated only when the former occurs, when an act of law renders the individual ‘an object — the matter of a juridical relation, not the subject of it’. Following the latter reasoning, a violation of the right would only occur in cases of slaves, deprived by law of the entitlement to rights and duties. No violation of Article 3 occurs in a ‘de facto situation that would deprive the individual of the possibility of exercising the rights to which, however, he has not been refused ownership’ — such as the situation of forced disappearances.

Only in 2009, in Anzualdo Castro v Peru, did the Court explicitly reconsider its position and acknowledge a violation of disappeared persons’ right to juridical personality. The legal reasoning underlying the Court's decision states that Article 3 is violated in case of individuals whom the Law fails to protect, whether de jure or de facto. The Court emphasizes a fundamental feature of forced disappearances: the state's refusal to acknowledge that the victim is under its custody and provide any information in this regard. Thereby, the Court compellingly argues that the Law has failed to protect the desaparecidos and demonstrates that persons who are denied juridical personality do not necessarily need to be objects of the Law or lack legal entitlement to rights and duties (as in the slaves’ example). Placed in a situation where they cannot exercise rights nor obligations to which they are entitled, desaparecidos are not protected by the Law. Whether the Law continues to grant them ownership to rights and obligations becomes irrelevant in the face of their de facto incapacity to exercise any of the latter.

Juridical personality and right to truth of the relatives of disappeared persons

The Court grounds the right to juridical personality on a juridical conception of human dignity as the innate quality and basis for the individuals’ entitlement and capacity to exercise rights and duties. Thus, ‘failure to recognize juridical personality harms human dignity’. However, pronouncements of the Court generally overlook the relationship between the family members’ right to truth and protection of their juridical personality. The Court's lack of focus on this relationship hinders understanding why protecting the family's dignity depends on knowing the truth. My hypothesis is that their dignity is violated because without truth relatives cannot fully exercise rights and obligations.

The UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances acknowledged that ‘family members are prevented from exercising their rights and obligations due to the legal uncertainty created by the absence of the disappeared’. This affects status of marriage, guardianship of children, right to social allowances, and management of properties. Especially in patrilocal cultures, women face legal difficulties when their partner is forcibly disappeared. The limbo in which these women live shows the failure of the Law to protect them and, ultimately, the violation of their dignity. While truth alone may be insufficient for the exercise of their rights, I argue that knowing the truth represents a necessary condition.

There are two main objections to my hypothesis. First, states have increasingly issued orders of presumption of death, or declaration of absence by reason of forced disappearance to overcome the legal limbo endured by relatives of desaparecidos. The presence of these documents alone would not constitute a violation of their juridical personality, even in the absence of truth. However, such certificates can only be issued with the consent of the family member and many are reluctant to provide it, as doing so would amount to renouncing hope of their loved ones’ return. The son of a missing person said: 'How can I proclaim my father dead? (…) Who am I to decide (…) when his life is over? (…) I will beg, but I will not do that’. This objection fails to prove that absence of truth leaves unhindered the juridical personality of those seeking it. The Court should always evaluate whether issuing these certificates restored the relatives' capacity to exercise rights, and whether, prior to the issuance, that capacity was violated.

Secondly, the Court has already ruled that the State’s refusal to disclose the truth violates the family’s rights to humane treatment and access to justice. This could suggest that the Court has already made a compelling case for the restoration of the family’s dignity and findings of violation of Article 3 regarding the disappeared’s family would be unnecessary, if not redundant. I believe the latter view deprives the Convention of one of its functions and contradicts the 'pro persona' principle that should assist in its interpretation. The founding fathers provided special protection to the right to juridical personality because its function is not guaranteed by rights to humane treatment and access to justice. The individuals' capacity to exercise rights is the democratic minimum for states that respect human rights, and particularly for those affected by violent conflicts. Any findings of violation of Article 3 would show that the protection of dignity should begin with an analysis of the de facto capacity to exercise rights and obligations. Ultimately, without this analysis the assessment of any rights violation is weakened.

Conclusion

The aim of this post is to open a new debate around the right to truth. If the Court systematically acknowledges the link between right to truth and right to juridical personality, the State will be forced to admit that a breach of the right to truth entails a violation of human dignity, not only because it causes suffering or precludes access to justice, but also, and most importantly, because it hinders the capacity of individuals to be subjects of rights and duties — which I contend is a necessary condition for the protection of their dignity.

OXFORD TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

OXFORD TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

This article has been published as part of a partnership between JusticeInfo.net and the Oxford Transitional Justice Research (OTJR), a network of high-level transitional justice researchers which is part of the University of Oxford. Justiceinfo.net publishes OTJR publications under the joint responsibility of its editor and OTJR.

Giulio Pagano is an LLB candidate at the University of Cambridge. He has a BA in International Studies from the University of Milan and an MSC in Criminology and Criminal Justice from the University of Oxford.