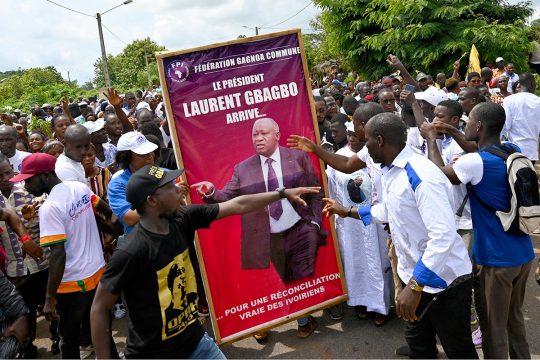

On 15 January 2019, the Trial Chamber of the International Criminal Court (ICC) acquitted Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé by a majority, stating that the prosecution had not provided evidence of all the required elements of the crimes against the accused. All eyes focused on Gbagbo because of his status as former president of Côte d'Ivoire. An immediate question was the consequences of this acquittal for his place on the Ivorian political scene.

This reminds us of a recent precedent in Kenya, where two major ICC defendants, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto, found in the proceedings against them a motivation for their political union, and made it a powerful electoral argument. Being able to present themselves as victims of external, even neo-imperialist intervention contributed to their victory in the presidential elections. Once elected, they were able to complain that the Court did not respect their immunity and they may have convinced the witnesses to stop speaking. Their reputation increased when the case was dismissed, so that they appeared as the heroes they are not.

The question is therefore, on the one hand, why an acquittal seems to improve the public profile of politicians and, on the other hand, what are the specific issues of the double acquittal in the Côte d'Ivoire case.

Acquittal is not innocence

The first question requires a simplified answer. Many people think acquittal means innocence and that if the prosecutor could not convince the court, it is because the charges were unfounded. However, nothing could be further from the truth. First, the prosecution may fail on technical issues, sometimes with private personal perspectives. I am thinking in particular of the Protais Zigiranyirazo case, a man considered central to the Hutu extremist movement in Rwanda, and prosecuted for genocide before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). The accused wrote a pamphlet expressing all his hatred of the Tutsi and it is difficult to doubt that his hatred did not lead him, in 1994, to participate in discussions on the identification of persons to be eliminated. However, the ICTR Appeals Chamber considered that the Trial Chamber was deeply mistaken about the burden of proof as well as the standard of proof. In such a case, it would have been logical to refer the case to another Trial Chamber. But no, the Appeals Chamber decided to acquit, opening the way for all possible speculation on this extreme option, which took no account of the merits of the case or the interests of the victims. It is difficult to infer from such an acquittal that the accused's innocence has been established.

Shortly before Gbagbo, there was also the case of Jean-Pierre Bemba, a former Congolese vice-president accused before the ICC of crimes committed in the Central African Republic in 2003. Here, the decision of the Appeals Chamber to acquit was equally technical, with additional complexity due to the interplay of judges' opinions: three out of five considered that he should be acquitted, but for different reasons. What a mess! Again, why not refer to a new Trial Chamber?

How many substantive acquittals?

Acquittal is therefore not necessarily the restoration of innocence because it may mean that what the accused person did was simply not found out. But that is the way criminal justice works: the monopoly of violence against the individual does not justify establishing responsibility in the absence of sufficient evidence, and as a lawyer I respect this principle.

Some acquittals, however, are more strongly in the direction of innocence. This is the case of André Rwamakuba, former Minister of Education during the genocide in Rwanda, where the prosecution case collapsed in its entirety, to the point that reading between the lines of the judgment one could wonder whether the case had not been fabricated. The reasoning of the Trial Chamber had been so harsh that the prosecution, despite an initial will to appeal, quietly gave up. But how frequent are these substantive acquittals?

way open for Blé Goudé

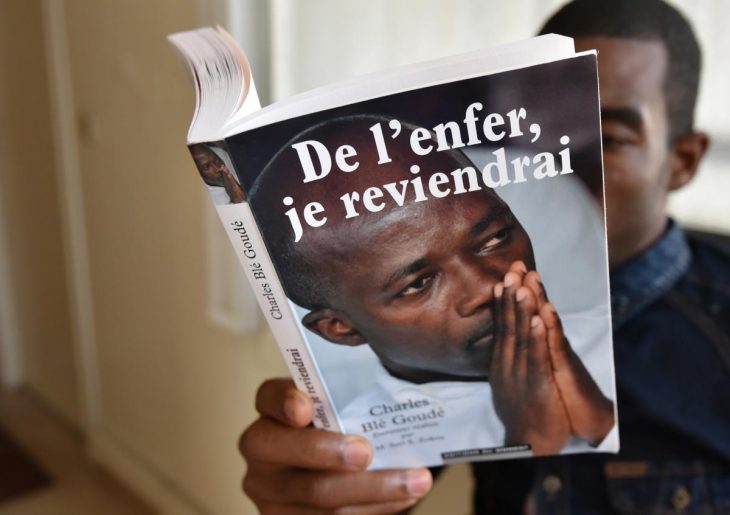

The second question, on the political consequences of the ICC's decision in the Ivorian case, seems to me to have partly missed the point. Because the real question should not focus on Gbagbo but on his “co-acquitted”, Blé Goudé. Gbagbo comes out of prison with a new aura but his age – 73 – is not in his favour. He can be expected to set about healing the wounds in his party unifying its supporters while continuing the battle against age and legal procedures. There is no guarantee that he will want to get involved politically, at least not at the forefront. He has found a clean image that he may not want to dirty by entering the ring.

President Ouattara's side is not in a better position. There are sparks between him and his former Prime Minister Guillaume Soro, and the risk of fire is not minor. Henri Konan Bédié, kingmaker but even older (84 years old), is mostly looking for a new alliance for him and his movement. Blé Goudé, by contrast, is young and dynamic, a force for the youth of the Gbagbo camp. The way has opened for him to throw himself back into the political ring and hope to capitalize, like others before him, on his judicial "martyrdom" and on Gbagbo's aura, whose companion in misfortune he has been much more than any other. This is the real risk for the political scene in Côte d'Ivoire.

However, in truth, it is not the acquittal at the ICC that creates this risk but the loss of power of the Ouattara-Soro duo, in association with Bédié. The failure of this alliance, conceived in 2010, makes this acquittal an opportunity for Blé Goudé more than for Gbagbo. The future will tell us what he will do with it.

Don't get the wrong target

International criminal justice must learn to play its part more effectively. Acquittal is not a problem in itself, but it should be rare if the prosecution did its job well. The prosecutor's office should not proceed with a case if it is not sure of its evidence. The rate of acquittals and dismissal of charges at the ICC – 9 people (Gbagbo, Blé Goudé, Bemba, Kenyatta, Ruto, Sang, Ngudjolo Chui, Mbarushimana and Gharda) compared with 3 convicted persons (Al Mahdi, Katanga and Lubanga) – is raising the alarm. We should not be distracted by the possible political repercussions when the important fact is the failure of the prosecutor. The national political impact is just a coincidence.

ROLAND ADJOVI

ROLAND ADJOVI

Roland Adjovi has been teaching since 2009 at Arcadia University in the United States. He was a lawyer assisting judges at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and then victim's counsel before the International Criminal Court. He has appeared before various other courts, including the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights and the United Nations Dispute Tribunal.