JUSTICEINFO.NET IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

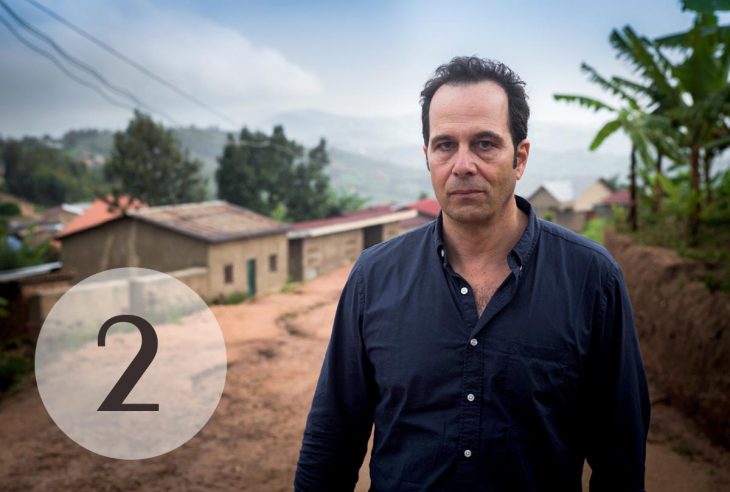

Philip Gourevitch

Journalist at The New Yorker and author

Journalist and writer Philip Gourevitch has kept going back to Rwanda for 24 years. In this second part of an interview with Justiceinfo.net, he reflects on the meaning of commemorations and on the relentless demand for justice, even when the genocide in Rwanda has been the most litigated in history. He also shares some of the challenges of writing on the aftermath of genocide, and explains why he’s been going back, again and again.

JUSTICEINFO.NET: The aftermath of the genocide is also about constructing, organizing, symbolizing memory. Rwanda has a lot of memorials to remember the genocide of the Tutsis. How do you see the commemoration process? Is it, again, a government policy or is it more meaningful?

PHILIP GOUREVITCH: I think it’s complicated and contradictory. Contradictory in the sense that while they are putting the country back together according to the idea that everybody is Rwandan first and foremost, that they are no longer defined by a Hutu/Tutsi division, during April, in commemoration time, they go back to the language of that. And people feel it very strongly.

It seems inevitable and right that there are certain times and certain places where commemoration is concentrated. All societies do that in one way or another, just as individuals do so in their private lives. And in Rwanda's situation, to manage the incredible wounds and passions and traumas and psychosis of the genocide, and the war – to regain some control, of public and private life, rather than to feel controlled by the force of that past, you had to say: we can’t be in this state all the time. And at the same time, there is this determination not to forget, even as you yearn to suffer less from your memories.

The state has different reasons and objectives in managing this balance than individuals, but at both levels, public and private, the need to find a modus vivendi with the past is there and evolves or changes over time. So ideally the balance sought by the state and the citizenry is broadly in sync, but when the events being memorialized define all that divides the people's experiences I don't know if that's possible, or what it would look like.

In the early days, I felt that a lot of the commemorative responses were quite spontaneous. As it became more formalized, the trauma that is released at the big stadium commemoration ceremonies is quite horrifying. A lot of survivors won't go near that scene.

In the early days, I felt that a lot of the commemorative responses were quite spontaneous, and there could be a lot of fury in them as well as all the other feelings you would expect. As it became more formalized, the trauma that is released at the big stadium commemoration ceremonies is quite horrifying – the screaming that sounds like seagulls, people literally convulsing and having to be carried out feet first. A lot of survivors won't go near that scene. Obviously a lot of perpetrators don't want to go near it either. Or people who fear that they might be seen as perpetrators. Suspicion is stirred up. The old darkness wells up. And then when it's over, it gets buckled back up again.

It's really not on the surface any more the rest of the year like it was for a while. So I'm left wondering what did people get out of that? I'm sure some people just take it in the way people take in church teachings even if they don’t entirely find them convincing, because it's a structure and a formulation that works to get them through the days. Rwandans are big church-goers and I get the impression that there's some of that going on here. And many people stay home. I remember in 2010 to 2015 or so, when people thought things were doing ok in Burundi, a lot of people from Kigali would go to Burundi for the week. People said they were being told at work: do not take a vacation during commemoration week, it looks bad. The hardest thing to know is what it means for the young people who were born since 1994, which was already by I think the 15th anniversary, half the population. What's it like to grow up with maybe silences at home, of various types, or insufficient explanations and to get this only from commemorations?

The genocide in Rwanda stands as the most prosecuted genocide in history: more than one million persons in Rwanda, 75 at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and symbolic trials taking place in ten other countries.

And it continues.

Indeed. Gacaca and the ICTR are over, but trials are still happening in Rwanda and in some European countries. Does the demand for justice last forever after mass murder?

The demand? Well, if you're a Rwandan, and you know that a guy who oversaw a church massacre in your community is living comfortably in Clermont-Ferrand and working in a pharmacy there, raising his children in bourgeois comfort of a sort, and everybody there just shrugs and says “well, you say he organized the massacre but enough is enough, monsieur”, it could make you furious. You'd say: No! Somebody’s got to get that guy.

Then again, Rwanda's relentlessness in pursuing these genocidaires is unusual. After WWII, some Jews became Nazi hunters and kept at it for the rest of their lives, but they mostly focused on very senior figures. And I don't know that I've ever come across stories or accounts of survivors of the Holocaust who say: I would like to go back, investigate and figure out who did this to my grand-father, who chased him out of his house, who put him on that train, who put him to death, and I want to haul them all into court. It probably wouldn't be that hard to figure out who those people were in some places in Germany, but most Jews just said: the hell with it. They say, it was Hitler, it was the war -- whatever category they put it in. And, of course, now they don’t live where it happened anymore.

Rwanda is unique, as you say, as the most litigated genocide. It’s also the only one where everybody lives intermingled in that way.

That's key. Rwanda is unique, as you say, as the most litigated genocide. It’s also the only one where everybody lives intermingled in that way.

But the government supports NGOs and groups in the West that do the hunt.

Right, there is some internal pressure from survivors to that. But I think it's a priority to them because they see those people as a political problem. They want the Western countries to assume responsibility for having accused genocidaires living in them: what are you doing with those people there? Are they influencing your thoughts? So part of it is putting pressure on those governments as much as it is on those suspects they're after.

After the genocide there was a diaspora of Hutu refugees and there was a diaspora of Hutu Power and génocidaires. To the government in Rwanda that is a threat.

After the genocide there was a diaspora of Hutu refugees and there was a diaspora of Hutu Power and génocidaires, white-collar professionals, some of them with means, who would find their way into a society and put forward their ideas, lobby governments and local churches. To the government in Rwanda that is a threat. There is a challenge to their legitimacy coming from those people, that is rooted in those crimes. So there is a convergence of interests. Justice may be the instrument, but the interest is: you are trying to delegitimize us, this is how we show that you have no legitimacy. I have never heard anybody articulating it that way in power in Rwanda but it seems to me clear that this is a significant and normal state interest.

Should there be an end to it at some point? I don't follow these cases closely – I read about them in news reports, so I don't presume to know the merits of any given accusation. But if a case is really serious and solid, I can't see why someone should be spared just because they've managed to get away with it til now.

For 24 years you have spent a very significant amount of your time investigating, reporting and writing on Rwanda after the genocide. What is it that attracts you as a writer?

I have luckily spent a bit of my time doing other things and writing about other things. I keep coming back to it because it confronts me with ultimately interesting questions. Most of us are never put to the sort of tests that many Rwandans can't escape in living together after the genocide. There are people in my life in New York who I know have said or done things that makes me not want to see them, or forgive them, been dishonest in some matter, or grossly selfish, or emotionally injurious to someone – in private or professional. I'm not talking about many such people but really I recoil at the prospect of seeing them. What a luxury! I don't have to. And if I do, really so what? You move along. And to think what all people see and know about what everyone they encounter in a Rwandan village when they walk a mile in any direction from their home, what they carry, what they manage, how they manage! The relationships and the social knowledge are so complex, and loaded, every mile like a complete shelf of Greek tragedies, with a few great comedies thrown in, too, of course. When I tell people at home about Rwandan life in the aftermath, some tiny subset of the sort of one mile walk I'm describing, they often say: I couldn’t put up with that; I can’t even start to think about it. And yet if Rwandans immediately got up and started killing the people next door a lot of people would say: there you go, those Rwandans, Hutus and Tutsis, they’re like cats and dogs, there is no hope for them.

The people who have been there for twenty-five years – they have reached extraordinarily deep into parts of themselves we don't know are parts of ourselves.

So something unexpected has happened. The people who have been there for twenty-five years – they have reached extraordinarily deep into parts of themselves we don't know are parts of ourselves. When they say they have no choice that's part of what they're referring to, too. When someone I talk to here at home says, I couldn't deal with – I now think, no, what you don't want to deal with is that maybe you could. I am not saying it’s perfect there, not even close to perfect. It can be hellish! Of course, it’s totally fraught! And, of course, it’s not taking place in a climate of freedom. I don't know if it could or couldn’t. I had a guy in Rwanda saying to me: “We’re lucky because we have a government that doesn’t really let us be free; and if we did what we wanted to do we’d be destroyed after the genocide." He was talking about the temptations of revenge. "It forbids us from doing what we want and as a result we get something that's a bit better.” I'm not saying I was convinced. I'm saying it's not a settled question.

Did he say how long they would need that lack of freedom?

Ha – nobody I've talked to there who doesn't say they need more freedom now, or needed it for a long time, has been able to tell me that. If they say they think it's better not to have it, it means they're afraid of it. And I'm saying when I hear that from people there, I don't know if they're right. Or I can't say I'm sure they're wrong. That's what I mean when I say it confronts me with ultimately interesting questions. I mean, they're bottomless. And I don't mean to suggest that this guy's attitude is by any means the universal attitude, only that it's something you hear there that you can't not consider. He's not saying it's great – he's saying it's not, but that he accepts something about the tradeoff.

Really, the genocide was the easy part in terms of thinking and writing about it. We know what we think about that.

Really, the genocide was the easy part in terms of thinking and writing about it. We know what we think about that. We understand the mechanism of division, of pitting people against each other – what broadly is called hate, though I think the word power is more accurate; you take weak or disempowered people and you give them power over one another.

I have just re-read Homer, the Iliad. We know that people really like to kill each other sometimes. Some people like to kill. My sense is those people are the ones who self-selected in Rwanda to emerge as doing a lot of the killing. That’s clear. They will say so, that they enjoyed it or were drawn to it. So we know all that. The question is: How do you put it back together?

I was under the perfectly reasonable notion that it would be a little bit less heavy, maybe even easier, to describe people living with each other than people destroying each other.

I was under the perfectly reasonable notion that it would be a little bit less heavy, maybe even easier, to describe people living with each other than people destroying each other. But the problem is, as I mentioned, that now they live with a detail of graphic knowledge and when you say: what do you know of that person you’ve reconciled with? They go and recite to you what they heard in gacaca, which is incredibly graphic and gory and harrowing.

In the first period that I reported there for my first book I felt that it was easy to convey the magnitude and horror of the violence without having to get gory. But if somebody now tells you “I was 10 and here is what happened” and you asked what it is to reconcile or to think about reconciliation, I can’t spare you, the reader, that gore, because that’s exactly what they’re dealing with, and they’re dealing with it not from the past – because half of it they didn’t see at the time – they’re dealing with it partly from the past and a lot of it from a few years ago. And I found that it ends up being very hard to write about because it’s so distressing. It feels like if you compress it you risk not giving it its due, and if you give its due it’s just overwhelming and repellant. So finding that balance means absorbing all of that into oneself and living with it.

Then you open the door of some house and the person who invited you opens the door to their self, and you go into this vortex with somebody.

When we first were in Rwanda, it was on the surface, like convulsing, at times almost physically surreal. Weird scenes popping up in front of you, strange encounters with random people saying wild, unexpected things, flashes like that. Now it’s a very smooth surface, it’s very calm, very quiet, very orderly. People are not haunted in a way that comes at you, they don’t have that vibe. Then you open the door of some house and the person who invited you opens the door to their self, and you go into this vortex with somebody. And you carry all of that back out the door into the normal present, it's like some extreme kind of time travel, those few steps in and out.

And so the aftermath is harder to write on?

The aftermath is ten times more interesting and harder. It’s much harder to understand and therefore to write about.

Here is a country that’s been through a genocide. It executed 24 people, then abolished the death penalty, kept revising laws to reduce penalties. As they saw that society could tolerate it, they dialed it down. It became less punitive, demanding enormous amount of acceptance and of recycling of people.

This goes against a lot of what we think in a punitive society like my country. This is some kind of complicated political balance. And it’s something that no society has ever gotten right. Has Rwanda? We can't even know that for some time. But Rwanda has got it to somewhere that you have to reckon with. Rwanda has gone further and faster towards dealing with it than most. Maybe that will turn out to be too far or too fast or both, or maybe it will surprise us again in other ways, for better or worse. But that makes it fascinating.

The other thing is: they talk. There is a line in Svetlana Alexievich’s book of oral history about Chernobyl where somebody says: all of us – and it’s very clear that they’re ordinary peasants in Ukraine – went through so many things that nobody had ever imagined and been through before, that everyone became a philosopher. Rwandans say things that sound deceptively simple in the language and the way they toss them off sometimes in the conversation, that actually shows that they’ve been into hell, then on a road out of hell, and that they have kinds of wisdom and insight that I don’t think are universally applicable but are universally interesting and informative.

Have you ever thought that fiction could be a better avenue for you to write about Rwanda?

There are certain kinds of extremity – especially very contested history and violence that involves a lot of arguments of what even is true – where the documentary form can be at least as rich or richer than fiction.

I have not felt that about Rwanda myself. I think it might be for some Rwandans. There are certain kinds of extremity – especially very contested history and violence that involves a lot of arguments of what even is true – where the documentary form can be at least as rich or richer than fiction. Or maybe it’s too soon for rich fiction. Maybe the problem of exposition is still too overwhelming. Great war novels often came twenty or thirty years after the war, not straight from the field.

Again, I am not Rwandan. I'm talking as a writer looking at it from without. My interest is to record and represent how Rwandans are dealing with it, as much as I can, because I find it deeply instructive, and often moving, and it keeps surprising me. I never went to Rwanda with an agenda. I usually went bewildered by it's challenges, and people I talked to gave me a framework for seeing some of what had happened.

How has it changed you?

I can never know how to answer that question. I don’t have a good answer because I don’t think it surprised me entirely. In other words my understanding of what humans are capable of and how power in history works was not turned upside down by getting close to Rwanda.

I say sometimes that I have become more forgiving of forgiveness. At first I found it incomprehensible. I feel like some things should be unforgivable. And then it pushes you back to: What’s the alternative?

I say sometimes that I have become more forgiving of forgiveness. At first I found it incomprehensible. I feel like some things should be unforgivable. I can forgive something that was done to me, maybe, but what kind of society forgives somebody for killing somebody else’s family? What does all that mean?

And then it pushes you back to: What’s the alternative?

And I have seen people in great difficulty and suffering find their way to a better place, when I really didn't see a way for that. I admire those people.

So it has changed me that way.

I might add that I'm now living in a country that feels like its being broken, not put together. That colors my understanding, I'm sure. There is one big, powerful, person stomping very hard right now on the bones of my country seeing how many he can snap. I don't know what he's after. But you see the ease with which one guy can make things more coarse, make things worse, attack, create crisis, sweep the spineless along with him, and you realize how much this is not a question of law, or of our rock solid system, but of custom, of social accord, and of chance – I mean what a freakish calamity that we have this man dominating these years. And its not just America that's in crisis, but so much of what used to look like the more stable parts of the world. So whatever confidence in a comfortable social-political-historical position people in what Rwandans call "outside" might have thought or wanted to think they could look at Rwanda from in the 1990’s seems a lot more fragile. And Rwanda’s fraught, troubled, complicated, totally unfinished and unpredictable-from-here struggle to put something together looks more like something about which nobody can say, oh well, we know better. That’s why I go back.

Interviewed by Thierry Cruvellier.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH

Philip Gourevitch is a longtime staff writer at The New Yorker, and the author of We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, stories from Rwanda (1998). He reads it aloud on a new audiobook which will be released on April 9. He also wrote A Cold Case (2001), and The Ballad of Abu Ghraib: Standard Operating Procedure (2008). Over the past decade he has been revisiting Rwanda periodically for a new book, You Hide That You Hate Me And I Hide That I Know.