Context: Uganda experienced some two decades of civil strife under Milton Obote I (1962–1971), Idi Amin (1971–1979) and Milton Obote II (1980-85). During this period, it is estimated that over 300,000 people died. In 1979, exiled Ugandans—including now-President Yoweri Museveni—invaded the country. Following a guerilla war, Museveni and his National Resistance Army (NRA) gained control of the country in 1986 and installed a "no-party" political system.

Since becoming president in 1986, Museveni has introduced democratic reforms, is credited with reducing abuses by the army and police, and improving the economy. Nevertheless, his own human rights and democratic credentials are subject to some strong criticism. He remains in power to date.

Museveni’s government either defeated or made peace deals with several rebel movements. However, the country was still blighted by a brutal insurgency, led by the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), in the north of the country. The LRA is accused of some of the worst crimes, including murder, rape, enslavement of women and children, mutilation of civilians (including cutting off body parts) and forced recruitment of child soldiers. At the height of the conflict, nearly two million people in northern Uganda were displaced.

The LRA was forced out of Uganda in 2005/06 and has since wreaked havoc in the Central African Republic, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Museveni negotiated a peace deal with the LRA in 2007, despite having referred its top leaders to the International Criminal Court. The ICC referral may have helped bring LRA leader Joseph Kony to the negotiating table. Nevertheless, the peace deal failed, largely because the LRA leadership did not honour it.

Transitional Justice Mechanisms

ICC: President Museveni referred the situation in the north of the country to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in December 2003. In October 2005, the ICC issued its first arrest warrants for five leaders of the LRA: Joseph Kony (the movement’s leader), Vincent Otti, Raska Lukwiya, Okot Odhiambo and Dominic Ongwen. They are accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

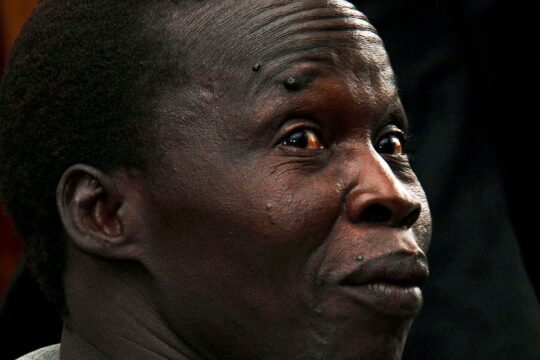

As the ICC has no police force, it must rely on the Ugandan Army, or UN forces in the neighbouring DRC or an African Union regional force tracking the LRA (with US military support), to arrest the suspects. Ten years after the arrest warrants were issued, only one of the suspects, ex-child soldier turned LRA commander Dominic Ongwen, is in ICC hands.

The ICC terminated proceedings against Lukwiya in 2007, following “strong evidence” that he was dead. Otti is also reported to be dead.

US forces working with the African Union (AU) Regional Taskforce in the Central African Republic took custody of Ongwen on January 6, 2015. After negotiations, he was handed over to the AU taskforce and the ICC took legal custody of him in Bangui on January 17. He was transferred to the ICC prison in The Hague on January 21 and his initial appearance hearing was held on January 26. Ongwen’s confirmation of charges hearing is currently scheduled for January 21, 2016. The ICC has separated his case from the other LRA suspects.

Ugandan press reports said Ongwen, who was a child soldier, could be the first ICC suspect to confess.

National prosecutions/ Other transitional justice mechanisms: At the height of the conflict with the LRA, Uganda introduced the 2000 Amnesty Act, under which thousands of former LRA fighters and abductees have left the group and been reintegrated through Uganda's Amnesty Commission. The Amnesty Act is nevertheless highly controversial, with some human rights groups and lawyers claiming it is contrary to both the Ugandan Constitution and international human rights law.

As part of the failed 2007 peace deal with the LRA, the government agreed to set up a special division of the High Court “to try individuals who are alleged to have committed serious crimes during the conflict”. The division, known as the International Crimes Division, was set up in 2008. Its jurisdiction includes “serious crimes”, including international crimes (genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity), and was extended to include transnational crimes such as piracy, terrorism and human trafficking. ICD head Joan Kagezi was assassinated near her home in March 2015 by suspected members of the Somali Islamist group al-Shabab, against which she was prosecuting a case.

According to ICTJ, Uganda’s International Crimes Division now has nine cases, most of which involve human trafficking and terrorism. Its first case, however, is against former LRA rebel leader Thomas Kwoyelo who was charged in 2010 with 12 counts of violating Uganda’s Geneva Conventions Act, including willful killing, taking hostages, and extensive destruction of property in the Amuru and Gulu districts of northern Uganda.

Kwoyelo’s trial began in 2011. But it quickly stalled because of Kwoyelo’s legal procedures claiming that he is eligible for amnesty under the 2000 law. In April 2015, however, the Supreme Court ruled that the trial could go ahead. It deemed that the Amnesty Act does not grant blanket amnesty in all cases.

The Uganda Department of Public Prosecutions (DPP) has also filed charges against former LRA field commander Caeser Achellam, according to ICTJ. He was apprehended by the UPDF in 2012 and “continues to be detained to gain further insights into LRA operations”. The DPP is also investigating two LRA commanders who were captured in the Central African Republic in 2013.

Uganda has long been at the heart of the peace and justice debate. Its ICC referral of LRA leaders has been controversial within the country, and Museveni’s own attitude to the ICC has been ambiguous. In addition to the Amnesty Law, Uganda has a long tradition of traditional justice, which has been used in villages to reintegrate returning LRA suspects. Many people in the country see the ICC in particular as an obstacle to such reconciliation.