In the heat of Georgia’s presidential election late last year, an International Criminal Court (ICC) investigation suddenly became a campaign issue. It was so serious that Nika Jeiranashvili, executive director of Justice International, an international NGO, decided to rush back to his home country from The Hague to try and help diffuse a situation that he feared could spark civil conflict.

“Ultimately, what it showed was there was a critical need for information,” Jeiranashvili said, due to the fact that the ICC had failed to adequately explain its investigation into crimes committed on all sides during Georgia’s 2008 war with Russia and forces of the breakaway region of South Ossetia. He and other civil society members took to social media, television and the press to emphasize the ICC’s neutrality amid rumours that the investigation could be used to target military officers for political purposes. “We had to step in,” Jeiranashvili said.

Three years of investigation and little information

The controversy erupted following remarks by the winning candidate, Salome Zourabichvili, who blamed the administration of former President Mikheil Saakashvili for starting the war. Some politicians started accusing the government of initiating the ICC investigation in order to target Saakashvili and his allies, and military generals then waded into the discussion, said Jeiranashvili in an interview with JusticeInfo.net in Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi. “You could almost see they were taking sides – the government and the previous government,” said Jeiranashvili, who met with some generals. “It could have led to a split in the armed forces, even civil war.”

More than three years into the investigation – the first launched by the ICC in a non-African country – almost nothing about its progress has been made public, and civil society groups say the court’s lack of outreach has left a dangerous void of information. Kapuo Kand, who represents the ICC in Georgia, said the court has made efforts to reach out to the public and to counter rumours. “I gave an extensive interview to Georgian public television at the end of December about some issues raised in the campaign,” he said. He added that the ICC registrar, Peter Lewis, was in Tbilisi for a regional seminar in late October and also gave interviews, as did a senior member of the ICC Prosecutor’s office, Phakiso Mochochoko.

Noting that up until April the ICC office in Tbilisi has consisted of himself and an assistant, Kand said his outreach strategy is to meet with victims, as well as civil society groups, academics and others who can disseminate information through media and other contacts. “There has been a lot of misinformation around the ICC in Georgia,” said Kand. “It’s not an easy period in general.”

The ICC standard answers

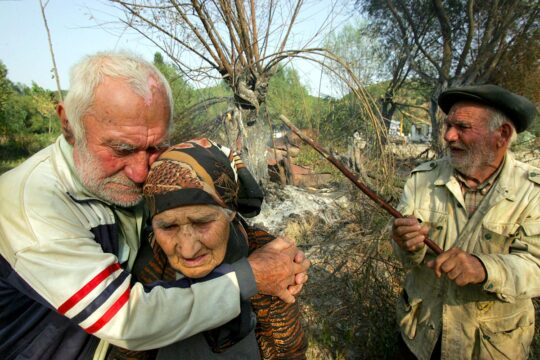

Little is known about the ICC even among victims of the 2008 war, according to a recent survey carried out by civil society groups among the approximately 30,000 people who fled their homes in South Ossetia and remain in settlements in territory controlled by Tbilisi. Of those surveyed, 49 percent reported that they had never heard of the ICC, according to Nino Jomarjidze of the Georgian Young Lawyers Association. Upon further questioning, she said, it emerged that about half of those who said they were familiar with the ICC were actually confusing it with the European Court of Human Rights, which is considering two cases filed by Georgia against Russia in relation to the 2008 war. Even those who had heard of the ICC knew no details about the investigation or its possible outcome, said Jomarjidze.

That is hardly surprising – the court has been extremely tight lipped. “Investigative activities are, and must remain, completely confidential,” the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP), said in response to a request for comment by JusticeInfo.net. “This is required in order to preserve the integrity of the investigative process and the evidence collected, as well as to ensure the safety and security of all involved in the course of the investigation.” The OTP added that “there is no specific time-line, and the investigation will take as long as required.” Kand also stressed that the court is not political, and that it functions as an independent judicial institution.

That is the standard answer civil society groups have received as well, but it’s not good enough, said both Jeiranashvili and Jomarjidze.

Fear and intimidation

Jeiranashvili said the ICC needs to manage expectations among victims who may assume that they will receive compensation for lost property, or be able to return to their homes at the end of the process. Jomarjidze argued that the OTP could release information that would not compromise its investigation, but would instil a sense of confidence in the process among victims. Similar investigations have disclosed, for example, the number of victims and witnesses interviewed, she said. “What we want them to do first is to share even some general knowledge about the investigation,” said Jomarjidze. “When you don’t know information about their activities, how can you trust them? How can you decide whether or not to cooperate?”

Building trust among victims is especially important as they are living in a climate of fear, said Jeiranashvili. Pro-Russian groups have circulated among displaced communities to discourage them from cooperating with the court, he said, while abductions have occurred along the administrative boundary line.

One of the most high profile cases involved Archil Tatunashvili, a former soldier in the Georgian armed forces who had served in Afghanistan as part of his country’s contribution to the NATO mission there. Tatunashvili died while being held in detention by authorities in South Ossetia who kept his body for almost a month before sending it over the boundary, which is controlled by Russia. Jeiranashvili said the incident sent a chill through communities of people who fled the war, who thought: “If Russia can do this to him, what can they do to us?”

No access, no cooperation

To complicate matters further, neither Russia nor the South Ossetian authorities are cooperating with the investigation, and Russia withdrew in 2016 from the process of joining the ICC. Investigators have no access to South Ossetia where the majority of war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly occurred, including the torture of prisoners of war, as well as widespread attacks against civilians and destruction of property that drove ethnic Georgians out of the region.

Jomarjidze urged the ICC to speak out about the barriers investigators are facing. “It would be very important to publish a statement about the issue and encourage Russia to cooperate with investigation,” she said. “It could encourage other states to call for Russia to cooperate and to give access for the OTP to South Ossetia.”

That lack of cooperation raises the possibility that if the investigation does result in arrest warrants, only citizens of Georgia – a member of the ICC – would face trial, even though the bulk of the allegations are against Russian and South Ossetian forces, according to civil society groups.

Due to a dearth of information, many people were not aware that the ICC was looking into accusations against Georgian soldiers until the issue arose during the presidential election. “This is why the public went crazy last year,” said Jeiranashvili. “When they heard that any Georgian serviceman up to high-ranking generals could face charges, it was unacceptable.”

Without more information about the investigation and the ICC in general, he added, such a scenario is likely to repeat during parliamentary elections next year. “This will happen in the future as well,” said Jeiranashvili.