In 1957, Tunisia became newly independent and quickly abolished the Sharia and Rabbinic courts. Judicial orders were unified under the same banner of civil justice. Later, the country signed several international conventions against torture and abuse. Laws and circulars were published on the rights and duties of detainees. But very soon an authoritarian regime was established, tolerating no dissenting voices and putting justice and prisons under its control. They became tools to better gag, terrorize, humiliate and punish.

The final report of the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD) notes that, out of the 57,000 victims whose cases were retained by this Truth Commission, 12,380 men and women complained that they had been unfairly treated by Tunisian courts. The IVD also received 29,137 complaints about the inhuman conditions of imprisonment in Tunisian jails -- 26,572 from men and 2,565 from women victims.

Parallel justice under Bourguiba

In the 1950s, when the new state was being built, President Bourguiba created a parallel justice system with the establishment of four special courts. The objective was to control public freedoms and harshly punish political opposition. Military courts were responsible for offences against the internal or external security of the State. They imposed death and life sentences and hard labour against the soldiers who attempted a coup d'état in 1962. In 2014, they imposed significantly lighter sentences - many cases were dismissed - on senior security officials in the Ministry of the Interior during the Revolution, when peaceful demonstrators were killed or seriously injured.

The High Court was created in 1959. It was set up to deal with possible cases of high treason committed by members of the government. It had absolute powers, its judgments were immediately enforceable and could not be challenged either by appeal or by appeal to the Supreme Court.

Then, in 1968, the State Security Court was created to deal with the "Perspectives" group of young left-wing students. Its verdicts were also not subject to any appeal. Totally subservient to the ruling party, two of its members sat in parliament. From 1968 to 1987 when it disappeared, it published 22 judgments against all manner of opposition movements, from trade unionists to Islamists, from Marxist-Leninists to Arab nationalists.

Control over magistrates and reprisals

In 1987, this Security Court was abolished by Ben Ali "but the use of justice through military courts, the administrative court and even the ordinary courts against the opposition continued and was extended to journalists and human rights activists. Trials were held without the voice of the defence. Other people brought before ordinary courts also suffered interference from the executive branch," the report notes.

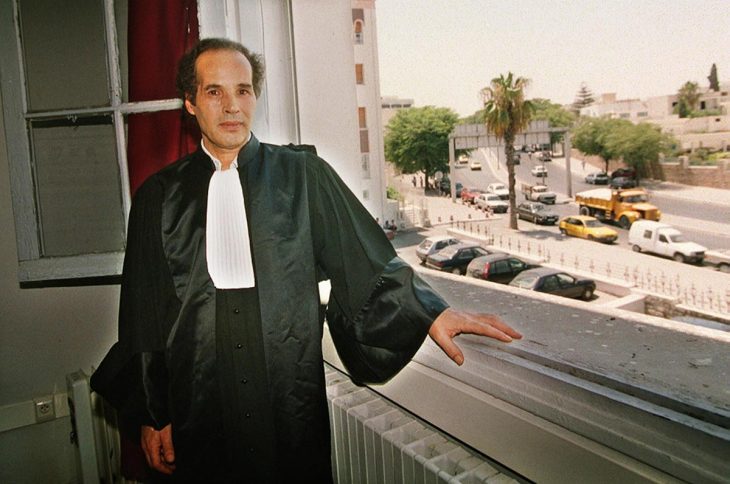

It was then through the Higher Council of the Judiciary (CSM) that the politicians interfered in the judicial system. The procedures for appointing, transferring, remunerating and punishing judges were the tools used to control. The CSM was chaired by the head of State himself. Rebellious judges, such as Ahmed Bensedrine, Rachid Sabbagh and the late Mokhtar Yahiaoui, were subjected to reprisals by the system.

The IVD interviewed the widow and daughter of Judge Yahiaoui. In its report, it restates his courageous positions against the lack of independence of justice. On July 6, 2001, he wrote an open letter to President Ben Ali in which he pinpointed the political control over justice, harassment and intimidation of honest judges and made headlines. Mokhtar Yahyaoui presided over the Tunis Court of First Instance. He was the first Tunisian judge to publicly express such insubordination. He was mercilessly punished: suspension, appearance before the disciplinary board, then dismissal.

Prisons, places of human deprivation

Iniquitous judgments against political dissidents were generally underpinned by inhumane conditions of incarceration. The IVD highlights the systematic human rights violations observed in prisons and found in the testimonies of 29,137 former victims. During all stages of prison life, the prisoner was subjected to ill-treatment and various degrading practices. "The President of the Republic himself appointed some prison directors, such as the director of the Tunis Civil Prison. He chose them according to criteria of firmness, toughness and ferocity," the report says.

Poorly lit, dirty, stinking, cold and damp in winter, suffocating in summer, detention facilities also failed to meet safety standards. Tunisian prisons were overcrowded; they received twice as many people as their capacity. Contrary to the provisions of Tunisian law and international texts, first-time offenders were mixed with repeat offenders, detainees under preventive arrest, dangerous criminals and those serving long sentences. Because of poor hygiene conditions and bad food, contagious diseases spread there. The IVD report takes as an example room n°1 of the Tunis prison. Its surface area was no more than 150 m², yet it housed 300 people, or 50 cm2 per prisoner.

"We found multiple cases of AIDS inside prisons. Virus carriers continued to share the same razor blades with other inmates. In prison, one blade was shared by an average of ten men," the IVD notes.

A doctor visited the detainees once a week, but emergencies could arise at any time. The only medicines available were psychotropic drugs, which were often the subject of high prices and trafficking. Urgent cases were left to suffer for days and nights, especially when it came to political opponents. Prisoners of conscience Hechmi Mekki, Lakhdar Sdiri, Mabrouk Zran and Ismail Khmila died during their more than late transfer to hospital. Mouldi Ben Amor and Sahnoun Jawhri died in pain in prison.

“For those people, I want one year to feel like ten!”

For the dictatorial regime, prison was not only a place where freedom was taken away, but also a place of humiliation. This widespread use of violence took on an exceptional dimension in the sanctions imposed on detainees for multiple reasons, including disobedience of orders. They were then kept in total isolation in the dampest and most unhealthy areas. Beaten up and insulted on a daily basis, they had their arms and legs chained to the foot of the bed and were forced to do their business on themselves. In Ennadhour prison, solitary confinement was in a cellar 36 metres underground. This is where Youssefist opponents were held in the 1960s and victims sentenced following the bread events of 1983. The people confined in this hell, the report writes, remember how they had to share their stale bread with the rats, at the risk of being eaten alive by these hungry rodents.

In Borj Erroumi prison, the director took in trade unionists, Communists and Islamists, forcing them to imitate the cackling of hens: "Repeat that you are here for the theft of a hen!" he would order them. Banned from sports and forced to clean the prison's rooms and toilets, their ordeal was methodical and planned. "For these people, I want one year to count as ten!" the director ordered his prison guards.

The attempt to destroy dissidents and their families continued after their release, through the administrative control mechanism. This was a very bad time for former political prisoners, who had to report to police up to eight times a day, as attested by the registry signatures of R.A. (from 7:30 to 18:30), whose registration record is published in the report. Under these conditions, it was impossible to work or to lead a normal family life. On November 12, 1997, A.R.B. committed suicide three months after his release from prison. He had had enough of this police harassment, especially since, under the pressure of the officers, his young wife had started to accompany him. "We'll undress her before your eyes and..." they warned. This was an unbearable threat, the worst torture, constantly echoing in his head.

IVD RECOMMENDATIONS

According to article 67 of the December 2013 Transitional Justice Act, the final report of the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD) contains "the truths established after verification and investigation, the determination of responsibilities, the reasons for the violations under this Law and recommendations to ensure that these violations do not recur..., recommendations, proposals and procedures to strengthen democratic construction and to help build the rule of law, recommendations and proposals on political, administrative, economic, security and judicial reforms...".

The IVD's report, published on its website on 26 March, therefore makes hundreds of recommendations relating to the various aspects of its mandate. With regard to institutional reform, the IVD recommends that the State provide the specialized criminal chambers, which have been operating since 31 May 2018 to try cases of serious human rights violations, with adequate protection and security, as well as all necessary means to compel members of the security forces to appear before them. The jurisdiction of military courts should be limited to military personnel who have committed military crimes, the report insists, and should not extend to civilian cases, as it is the case today. The government should also strengthen the independence of the judiciary by limiting the authority of the Executive to investigate or sanction judges.

The IVD also proposes that the Court of Auditors should be fully independent, with the creation of a body to oversee the funds of associations and political parties. It recommends that the position of the State litigation officer should become independent of the Executive, in order not to fall into plays of influence, considered to have damaged the IVD's efforts to recover public money stolen during the Ben Ali regime's time.

Finally, the Truth Commission recommends strengthening accountability measures to deal with alleged cases of professional misconduct in the police and thus ensure effective and transparent investigations. The report proposes the creation of an independent police oversight body, coupled with an intelligence agency under the supervision of the President of the Republic and subject to parliamentary control, with the aim of restructuring the security forces, preventing abuses and guaranteeing their political neutrality.

O.B.