It was raining lightly in Attécoubé, a small district of the Ivorian capital Abidjan, when we met Cathérine K, a victim of the post-electoral crisis that shook the country in 2010-2011. Now in her 50s, she greeted us in a modest café not far from her home. "I never liked talking to journalists. I don't want to be in the public eye," she explains. She has been a widow since the death of her husband, an electrician, who was killed during the violence in 2010-2011.

"A million is nothing"

Like several hundred victims of the crises that shook Côte d'Ivoire, Cathérine K received one million francs from the Ivorian government, through the Ministry of Solidarity and Social Cohesion. "When I learned that we were going to receive a million, honestly, I was very happy. I was planning to start a food business so that I could send my two boys to school without worry," the widow explained. But she says she quickly became disillusioned with the reality. "You have to have the money in hand to understand that a million is nothing, my son," she added gravely. "The government did what it could, but for a widow who didn't go far in school, it's not much."

Cathérine K can hardly remember where this money received in 2018 went. "I was so in debt that I didn't even feel like I received any money. As soon as I got it, I had to pay back those I owed. I had debts for food, rent, school for my two children," she says. "My husband did everything for the family. In this kind of situation, a million is nothing."

Cathérine does not hide the fact that she hopes for more from the Ivorian authorities. She hopes the head of State will re-examine the situation of victims of the crisis, nearly ten years after the events that left some three thousand dead in the country, according to official figures. "The president has always shown that he was thinking of us. May God touch his heart! He must do more, otherwise it is hard. We still feel the effects of the crisis up to today."

Funeral subsidy or reparation?

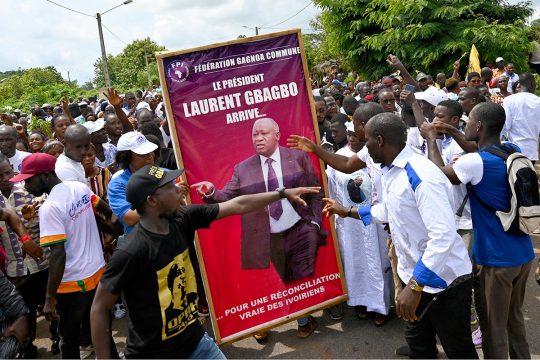

We then met Abdoulaye Doumbia, another victim, in ''Faitai'', one of the poor quarters in Yopougon commune that was one of the epicentres of the post-election crisis. Alert and talkative, he was one of the prosecution witnesses in the trial of Laurent Gbagbo at the International Criminal Court (ICC). He thinks the assistance so far is derisory.

"Chief Doumbia", as he is called here, believes that the Ivorian authorities have not been honest with the victims. "The State has deceived us. They told us that this million was for the funerals. What we were given was to provide ceremonies for the deceased. To our great surprise, we are told that this is our compensation," explains Abdoulaye Doumbia, who is the head of the district. Chief Doumbia, 65, is therefore waiting to receive what would represent for him real compensation for the victims. "Victims have rights that the state must pay in full," he says. "I went all the way to the ICC. I spent two weeks there as a witness. So far, I have not been successful."

Chief Doumbia believes that the victims of the Ivorian crisis are not getting the treatment they deserve. "We feel forgotten," he says with regret. "We are not told anything, we are being taken for a ride, and we do not understand. The State has not taken pity on us. The politicians who went into exile received millions when they came back, according to what we heard, even though they were the ones that sowed chaos. Today, they are the ones with rights. We who lost our children, people pretend it's nothing. What does a million mean to a person who lost the children that were everything to him?"

Among the poor of Yopougon

Abdoulaye Doumbia lost his three sons at the height of the post-election crisis. Compensation being 1 million per lost relative, he was paid three millions. He is convinced that the other victims who received this cheque have not been able to achieve anything with this amount of money to date. "When you have a funeral today," he says, "there are expenses in addition to your needs and those of your family. No one I know could even buy a television with that money. My two sons who did everything for me have gone and I have to go back to what I did when I was young, that is to say, working so that I can eat. May the State have mercy on us. Most of Yopougon's victims came from the poor neighbourhoods where we are now."

Imam Camara lives a few metres from the common courtyard where Chief Doumbia lives. This religious leader tells us with emotion about the day when "people dressed in fatigues and hoods" shot dead his five sons. Uncomfortable when it comes to expressing himself in French, Imam Camara is assisted by another son who acts as a translator during the interview. He is grateful for the government's gesture, but he does not hide his desire to receive more from the Ivorian authorities, particularly from President Ouattara.

"The crisis has affected us all. The president respected us by giving a million to each victim," he says at the beginning of our interview. But "one million isn't enough to do anything, because all the relatives come to ask you for money," he explains, sitting on the single sofa furnishing the living room of his modest house.

He hoped to be able to benefit from help to leave this house. "I lost five children. They destroyed part of my house. I even thought I would have had another place to live. We took this million. We thought we were going to get something else, but since then we have had no news from the government. I have written seven times to President Alassane [Ouattara]. I wanted him to at least receive me so we could look into each other's eyes to talk. But since then, I haven't had any follow-up."

Impact on the family

Imam Camara has a large family to support. He wishes to raise the question of the distribution of funds among relatives. "There are little sisters and brothers who are there and who are also victims of my sons' deaths. You can't keep this money to yourself. I remember that once the town hall came to give us 200,000 francs [about 300 euros]. I had to share with everyone. I only kept 5,000 francs for myself," recalls the 60-year-old.

Imam Camara, a member of the Côte d'Ivoire Victims' Collective (COVICI), said he had not given up hope of seeing the Ivorian authorities make another gesture in favour of the victims. "We really need help. I can't pay for my children's schooling because all my grown-up children have been killed. I'm old now. I can no longer do small jobs to feed the children. I know that the President is thinking of us and that he can do something more for the victims," he says, pointing to the room in which his sons were killed almost ten years ago.