Relations between these two United States allies in this volatile part of the world, destabilized by Pyongyang's nuclear programs and the territorial claims of China and Russia, have never been so bad. On August 15, the seventy-fourth anniversary of the surrender, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe sent his right-hand man to the Yasukuni Shrine to give a ritual offering for the repose of warriors who died for the Emperor, including fourteen war criminals convicted and executed after the Tokyo trials in 1946. This was enough to provoke the wrath of Seoul and Beijing, who immediately denounced Japanese militarism and negationism.

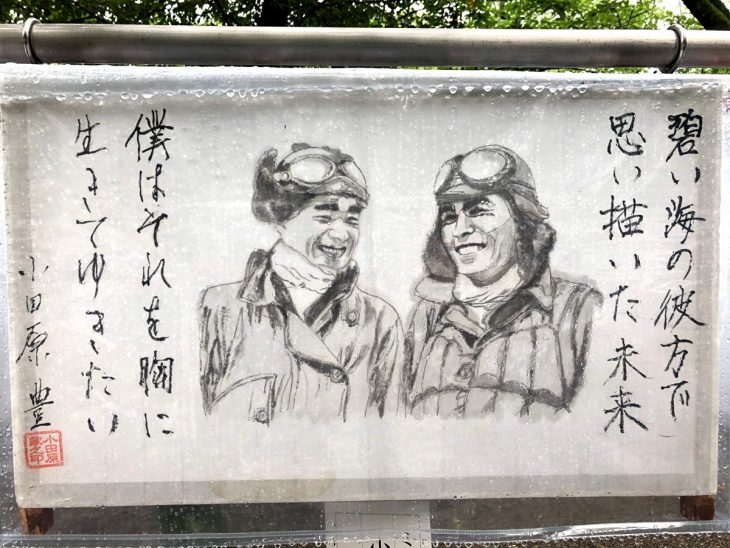

The Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo is in the middle of a 93,000 square metre park, one of the few green spaces in this sprawling city. This peaceful Shinto sanctuary is a place of pilgrimage commemorating the Japanese warriors who died fighting for the Emperor. This is what shocks Korea and other societies that suffered from the brutality of the Japanese occupation. A thousand war criminals, tried after the Second World War, are also honoured here.

When I went to the shrine one summer Sunday under a light rain, hundreds of older Japanese people had come there for a walk. Some watched martial arts demonstrations on the stage of the Noh theatre. Others commented on the tactics of fleshy adolescents fighting in sumo battles on the edge of the park. Still others meditated in front of the Shinto temple and offered some coins as usual. Were they simply taking a Sunday out or had they come to honour the souls of war criminals, including military and political leaders executed for launching the attack on Pearl Harbour and allying themselves with Nazi Germany? The first hypothesis is the most likely. In Japan on August 15, the date of its unconditional surrender, there were only extreme right-wing activists and a few nostalgic people marching in imperial army uniforms with the flag of militarist Japan defeated in 1945.

Honouring war criminals

Today, the Yasukuni Shrine nevertheless embodies Japanese militarism. As Professor of Diplomatic History Higurashi Yoshinobu explains in Nippon.com, Nagayoshi Matsudaira (1915-2005), the priest in charge of the shrine, was a senior officer during the Second World War. His father-in-law was Vice-Admiral of the fleet and was shot as a war criminal by the Dutch authorities. Matsudaira has always denounced the Tokyo trials as victors’ justice. That is why, as soon as he was appointed in 1978 to head the shrine, he decided to honour class A war criminals (military and political leaders convicted of "crimes against peace"), to the great displeasure of countries that had been occupied by Japanese troops. Some 1,000 other Class B and C war criminals (convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity) had already been honoured there between 1958 and 1969.

A museum was subsequently built next to the Yasukuni Shrine. The museum tells the story of Japanese history in a nationalistic tone. It justifies the attack on Pearl Harbour, saying that because the United States had imposed economic sanctions on Japan, the country attacked the US to escape asphyxiation. It says nothing about the Nankin massacres or crimes committed in Korea, China and elsewhere by the imperial army.

Symbols reversed

It is an extraordinary reversal of symbols, for the Yasukuni Shrine was first created as a symbol of reconciliation among the Japanese in 1869, the year after restoration of the Meiji era (1868-1912) when the Emperor's supporters overtook those of the Shogun. According to Shinto tradition, the shrine was a place of pilgrimage to commemorate the souls of the dead warriors, regardless of which side they fought for. Researcher Ryosuke Kondo, a specialist in public spaces, points out that the shrine was for a long time the symbol of intra-Japanese reconciliation, but also of Japan's modernization, importing Western techniques and welcoming French circuses and horse races to Yasukuni in the late 19th century alongside sumo wrestlers. It was here that one of the first modern Japanese gardens was built, combining traditional aesthetics of the lake-stroll style with Western features such as fountains and lawns.

And yet it is this seemingly peaceful place, symbol of reconciliation and openness to the West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that now embodies a nationalist Japan, to the point of being the catalyst for the current diplomatic crisis between Japan and its Korean and Chinese neighbours. In addition, Shinzo Abe makes no secret of his desire to repeal Article 9 of the Constitution, passed in 1947 under American occupation, which states that "Japan renounces war" and cannot "maintain land, naval and air forces or other war potential". For the time being, the Prime Minister has not managed to obtain a two-thirds majority in parliament which would allow Japan to build a real army.

Compensating forced labourers in Korea

The Japanese-Korean crisis comes in the context of a historical dispute, after a Korean court ruled in 2018 that Japanese companies should compensate Koreans forced into labour when their country was under Japanese occupation between 1910 and 1945. This court decision reopens the debate on Japanese war crimes, including the use of thousands of sex slaves, a case that both governments had closed. It is true that the Japanese government has never made a formal act of contrition like Germany, even though in recent months the brand new Emperor has expressed his "deep remorse".

Events have followed one another in this crisis, to which are now added economic and security dimensions. Japan refuses to supply South Korea with essential components for the manufacture of semiconductors and flat screens. Then recently, the two countries ended their cooperation in the exchange of security information, even though they are allies against North Korea. This is a worrying crisis between Seoul and Tokyo in a region under tension from the territorial claims of Moscow and Beijing and the Pyongyang nuclear programme.

Perhaps the Japanese government would be well advised to follow the example of German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who on 1 September 2019 apologized to the Polish victims of German aggression 80 years ago. A gesture by Japan towards the countries it occupied would allow it to start defusing the recurring tensions around the Yasukuni Shrine.