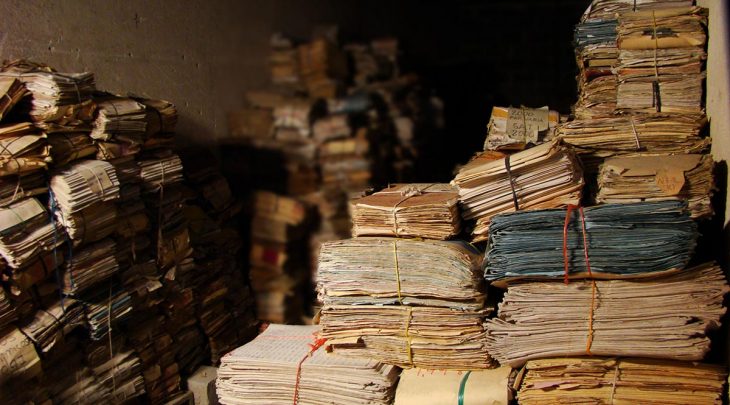

It’s a huge challenge, says US archiving expert Trudy Huskamp Peterson, to get transitional justice mechanisms “to recognize that when they end, there is a long-term life that has to be preserved for these records, that the utility of these records continues and sometimes becomes even more important over the long term”. The other main challenge, she told Justice Info, is getting them to start thinking right from the beginning “who is going to take care of this stuff after they finish”. Most often they do not think about it until the end, and then it’s a scramble. In most cases “it’s risky to just leave all the records in the country because various governments come and go and they may not want evidence to continue to exist,” she says.

Thijs Bouwknegt, a Dutch transitional justice expert at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies agrees that what is done is often “too little too late”. The NIOD is a public institution in the Netherlands that holds some important records related mainly but not exclusively to the Second World War. It has been involved in support for archiving projects in other countries, such as digitizing the gacaca records in Rwanda. The Netherlands is home to many important international courts and active in supporting transitional justice around the world but, according to Bouwknegt, generally less interested in “after care”. It seems the Swiss have developed a strategy and a certain expertise in this domain.

Providing expertise

Amid various initiatives by national and regional governments, NGOs and others, Peterson says Switzerland is “by far” the country most active in this field. “Switzerland is a government that has long looked at dealing with the past. They have funded projects all over. In a big project on which I worked they almost totally funded the preservation of the nuclear claims tribunal records in the Marshall Islands. So, they have a long track record.”

Switzerland has a “Dealing with the Past” programme within the foreign ministry. Its taskforce coordinator Christian Schläpfer says the ministry’s “systematic engagement in the area of Dealing with the Past goes back to around 2011 when our Taskforce was created”. Activities involve providing expertise and sometimes acting as a safe haven for archives related to transitional justice. “Switzerland is receiving increasing numbers of requests to act as a safe haven for archives, but it takes a while to put a solution into practice, as complex legal and sometimes political considerations need to be take into account,” he told Justice Info. “Providing expertise, on the other hand, happens upon request by our partners and is much less resource-intensive.”

Since 2011 the foreign ministry has been working with the Swiss Federal Archives and the NGO Swisspeace on an “Archives and Dealing with the Past” programme. Examples of its initiatives, according to Schläpfer, include supporting a “system analysis and proposed solution for the management of the data” collected by the Special Criminal Court in the Central African Republic; for the Extraordinary African Chambers in Senegal (Hissène Habré trial) and Burundi Truth and Reconciliation Commission, supporting the safeguarding of the physical archives and their digitalization; and supporting the design of the data collection and archiving system for the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission in Mali.

Swiss safe haven

As well as providing expertise, Schläpfer told Justice Info that there are “three cases” in which Switzerland holds transitional justice related archives from other countries for safekeeping. These include the archives of the Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal (NCT), which handled victim claims related to US nuclear testing. “These archives are still physically located on the islands but in very difficult climatic conditions - the general climatic conditions but also rising sea levels,” says Schläpfer. “Originally it started as digitizing these archives, with which we helped, and once they were digitized we managed to bring these digital copies to Switzerland and integrate them in the Federal Archives.”

The conditions of access to these archives are defined by the authorities of the Marshall Islands. In the other two cases, which Schläpfer preferred not to disclose, he says it is “more a question of having a security copy somewhere in a safe space in case that's necessary”, but there is no access to them. He told Justice Info they include police records that might be relevant for transitional justice purposes such as accountability or vetting. According to Peterson, the Swiss were “very important funders of the Guatemala Police Archives Project to try to preserve the police archives in that country”.

Neutrality gives credibility

Schläpfer says Swiss initiatives in the field are part of government peace policy, since “we are generally engaged in supporting transitional justice processes” and “we realized just how central archives actually are to these processes”. “We’ve noticed that the more useful they are, the more likely it is that they are at risk for whatever reason,” he told Justice Info. “These risks can be environmental, as we saw, but also political, of course.”

Asked why countries might trust Switzerland with their sensitive archives, Schläpfer says “we are not the only players in the field”, but he thinks Switzerland has an advantage. “It’s linked to our neutrality, and that we don’t really have any stake, we’re not suspected of having a stake, so that gives us more credibility. The other aspect, of course, is that we have made available some resources over quite some time for this type of activity.”

Schläpfer says that in developing this “niche”, Switzerland has introduced an “approach that resulted in guiding principles”. When it acts as a government to safeguard transitional justice archives from another country, there is always a contract, otherwise “there are too many open questions”, such as ownership and access to sensitive information. These guidelines are currently also used by various actors engaging operationally in safeguarding transitional justice archives, according to the ministry.

Scattered around the globe

Peterson says the records of a number of tribunals and truth commissions are held in other countries. For example, “the records of both the Guatemala and El Salvador truth commissions are in the UN in New York” and “the records of the truth commission of Liberia are in a university in the United States”. The archives of the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia are in the Netherlands, while those of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda are in Tanzania and remain accessible through the UN Residual Mechanism.

Those of the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) are in the Netherlands, at the national archives, but remain the property of the SCSL Residual Mechanism. Bouwknegt says this was a “rescue mission” because “paper doesn’t fare well in the Sierra Leone climate” and they do not take up too much room. In the Netherlands, he says it is all about space, which is “very expensive in this country” and can be a cause of friction over who pays for what.

In terms of ownership and who pays for what, Peterson says she doesn’t think this is a big issue for the UN tribunals because “they were created by the UN, they are UN records just as any other UN archives would be”. But, she continues, “when you have these joint bodies like in Cambodia, then we have real trouble figuring out who gets what, for what purpose and when”. And so, she says, “I really plead with these international bodies, these truth commissions, these tribunals. When you set yourself up, think about who is going to take over the archives when you are no longer working”.