JUSTICEINFO.NET: You have analysed the archives of the dictatorship in several books. What are they composed of?

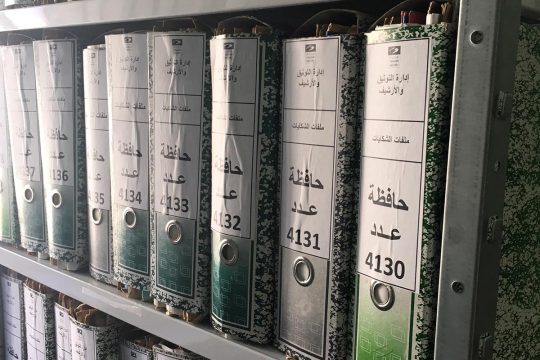

FARAH HACHED: It is quite difficult to explain the notion of "archives of the dictatorship". We have established three criteria. The first one is the bodies we are talking about. So the dictatorship archives could be constituted by documents belonging to these structures: the Presidency, the Ministry of the Interior, the former ruling Democratic Constitutional Rally party, embassies, other public administrations, militias, where they exist, and neighbourhood committees. We excluded the army archives because they require specific research and analysis. With regard to the purges, judgments handed down by military judges and unfair trials can theoretically also be included in the archives of the former regime. The second criterion is content. These archives may contain several types of information: personal data concerning key named persons of the dictatorship or opponents of the regime, people who were not politicised but were perceived as such, information on the functioning of the administrations and data concerning national security. The third criterion is the purpose of the information. The archives of the dictatorship do not arise from normal administrative functioning, nor are they linked to “normal” national security concerns, but rather served a strategy to install, strengthen and perpetuate the dictatorship.

The archives of the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD) have been transferred to the national Archives. The audiovisual testimonies of victims have remained under seal at the Prime Minister’s office. Do we need a specific law to guarantee the security and accessibility of these documents?

A distinction must be made between the archives of the dictatorship and those of the Truth and Dignity Commission. As part of our work, we have advocated the enactment of a specific law on the archives of the dictatorship to protect them from alteration, modification, theft, manipulation or destruction. Concerning audiovisual testimony behind closed doors, this question must be examined on a case-by-case basis in the framework of transitional justice: did the victim ask for his or her statements to remain secret, or did he or she testify so that his or her story could be made public? The choices of each person must be respected. For those who have opted for secrecy and confidentiality, the law on archives of 2 August 1988 applies, i.e. as long as they are alive their testimony remains under seal. It can only be opened 60 years after their death as laid down by the law. In the context of legal proceedings, such testimony is accessible to the judges of the specialized chambers. The law also provides for derogations in favour of historians and researchers.

Transfer the archives of the dictatorship to the National Archives, yes, but they should not be managed directly by the latter but by an independent committee”

Is it a problem that the national Archives are a government institution?

When we started working and especially studying examples like Germany and Poland, we said we need a specific body to contain the memory and archives of the dictatorship and its victims, as recommended by the IVD. What we discovered in the course of our research and our discussions with those responsible for remembrance structures made us change our mind. Why? For two reasons. The first relates to the enormous cost of such a body, which would have to manage a huge amount of archives in addition to a large number of educational activities. Does Tunisia in its economic crisis situation, coupled with the current Coronavirus health crisis, have the means to do so? I think that under the circumstances, this project is not a priority for the public authorities, nor is it realistic. The second relates to the risk of political instrumentalization of such a body. This is what happened in Poland, for example, with the rise of the right to power and damage to the reputation of political figures. Even if it was later realized that assumptions made about them were not true, suspicions will continue to weigh on them. These two elements lead us to believe that the best solution would be to transfer the archives of the dictatorship to the National Archives, but they should not be managed directly by the latter but by an independent committee made up of various members, including the director of the National Archives and the president of the IVD. This recommendation was made at a time when the truth commission did not yet exist. We proposed that the archives be physically managed by specialists from the national Archives, who are equipped in terms of infrastructure to receive them. It should not be forgotten that we are talking about masses of documents, from a small Post-it found on the desk of a ruling party administrator to strings of files on opposition activists. However, the control and responsibility for these archives should not lie with the director of the Archives, who is not legally independent, but with this independent committee. The national Archives would be like a service provider for this independent committee. As far as the IVD archives are concerned, I think we cannot ignore the Commission’s procedures manual and its recommendations on its documents. The alternative would be for the law establishing the aforementioned committee to develop a chapter on the IVD archives.

It is time for the government to assume its responsibilities after the IVD concluded its work and the publication of its final report.”

Do you think that today the national Archives with the means at their disposal can manage the IVD's archives well?

I think that in our current context, namely a democracy under construction, the archives of the dictatorship can be left under the authority of an independent committee. Questions of awareness- raising and education are part of the remit of the Human Rights Ministry, which would have among its prerogatives implementing the recommendations of the IVD's final report. In Chile the government, through its Secretariat of State for Human Rights, has taken up the recommendations of the transitional justice process, carrying out a number of reforms and conducting awareness-raising and information campaigns. For a country like Tunisia, with its limited means, this alternative may be interesting. Pursuing the objectives of transitional justice in Tunisia could be one of the priorities of the Ministry [of Human Rights]. This cross-cutting ministry can very well coordinate actions with the Ministries of National Education, Higher Education, Culture, Women and so on. It is time for the government to assume its responsibilities after the IVD concluded its work and the publication of its final report. The recent presidential and legislative elections, which came as a surprise to all, showed that Tunisians chose candidates who are favourable to the process.

What can the President of the Republic do with regard to the archives?

The President is the guardian of the Constitution, and therefore has broad powers in terms of respect for human rights. The Head of State can put this issue, which seems to be close to his heart, back at the centre of the debate by organizing events and conferences on this subject. As he has prerogatives in matters of national security, he can initiate reforms in conjunction with the Ministry of the Interior. The President has the Tunisian Institute for Strategic Studies under his authority, and in this context he can launch training courses and awareness-raising activities for decision-makers on the reforms to be undertaken in this post-IVD period, when the recommendations of the Commission are waiting to be implemented.

The examples from the former eastern bloc and South America have encouraged us to reflect on a specific model for Tunisia.”

How did the countries of the former communist bloc regulate and manage their archives? What relevant lessons can be learned?

There are those that opened all their archives, such as Germany and Poland. Others closed everything, such as Spain. I am in favour of a local and original model that takes into account our conditions, those of a very difficult economic and security context. Therefore, we cannot make all the archives public without processing them. They certainly contain information about opponents of the dictatorship, but among them are not only human rights activists but also jihadist groups, for example, which still pose a threat to national security. The examples from the former eastern bloc and South America are very interesting, and have enriched our research and reflection. At the same time, they have encouraged us to reflect on a specific model for Tunisia. Our proposal is based on our possibilities, and there are many of them.