On 30 June, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) celebrated 60 years of independence. But the surprise event did not come from Kinshasa. It happened in Brussels, in the former colonial power. On that day, in a letter to the president of the DRC, King Philippe expressed his "deep regret" for the suffering inflicted on the Congolese people during the time when this huge central African country was under Belgian rule. He is the first reigning sovereign to express such regrets for the colonial violence, far from the condescending speech made by his uncle, King Baudouin, on 30 June 1960, when he declared in an official speech to the representatives of the Congolese nation: "In the face of the unanimous desire of your people, we have not hesitated to recognize, from now on, this independence. It is now up to you, gentlemen, to show that we were right to place our trust in you."

Truth commission or parliamentary commission?

The speech of the King of the Belgians is not an isolated sign of acknowledgment. It comes at a time when the Belgian state has decided to open a deep and complete reflection on its colonial past, in the DRC as well as in Rwanda and Burundi. On 17 June, an agreement in principle was reached at the Conference of Presidents of the Chamber (the Belgian Parliament) to set up a committee to work on Belgium's colonial past. And on 24 June, this process was truly set in motion by the Chamber's Committee on External Relations.

The initiative, born out of the worldwide movement triggered by the murder of Georges Floyd in the United States, could inspire other former colonial powers. The aim is to set up a “Truth and Reconciliation” Commission by September, the outline of which must be defined by 21 July, the Belgian national holiday, at the latest. The future commission will take the form of a sub-commission, or a special commission or a commission of inquiry.

According to the Belga press agency, MP Els Van Hoof, chairwoman of the external relations commission, announced that the preparatory work for the future commission will be entrusted to two federal scientific institutions, the AfricaMuseum in Tervueren (formerly the Royal Museum for Central Africa) and the Kingdom's General Archives. "The working group will already meet next week for the first time with the first opinions of these two institutions," she said on June 24. "And this week, you [members of the Foreign Relations Committee] will also be able to give us the name of an expert you have in mind. We need to be able to get off to a fast start in order to define the mission to be entrusted to these experts," she added.

Two more limited precedents

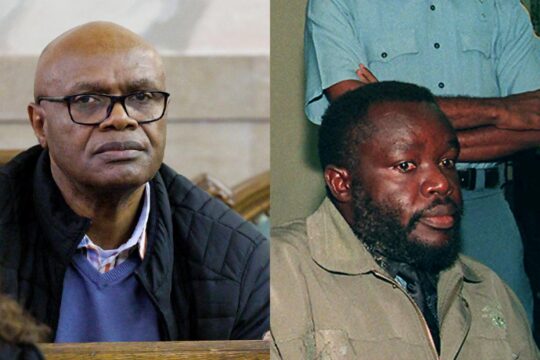

The initiative is a landmark but it is not the first attempt in Belgium to look into its colonial past. Previous parliamentary work has addressed the responsibility of the Belgian state in two criminal cases committed in its former colonies. In 2000, a parliamentary commission of inquiry was set up to determine Belgium's role in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the Prime Minister elected in the aftermath of Congo's independence in 1960. The commission was set up following the publication of the book "De moord op Patrice Lumumba", by sociologist Ludo De Witte, which recounts how the famous Congolese politician undermined the ambitions of the Belgian state in the Congo after independence. As recalled in the motion tabled by the green parliamentarians in Parliament (which will serve as a basis for the creation of the future commission), this parliamentary inquiry had only led to the recognition of the moral responsibility of the Belgian state in this assassination. On 1 July, the Belgian public prosecutor's office announced that it was studying the possibility of prosecuting the two Belgian suspects still alive for war crimes, adding that judges have requested access to the closed-door testimony gathered by the parliamentary commission, according to The Guardian.

Then, in 2018, the House passed a resolution acknowledging the responsibility of the Belgian state in another grim case of colonization, that of the segregation of Métis children in Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. Once again, it was the publication of a thorough investigation on the subject that prompted the state to react. "Black-White, Metis: Belgium and the Segregation of Metis in the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi (1908-1960)," written by Assumani Budagwa, recounts, among other things, how children born to a Belgian and a Congolese woman were abandoned in orphanages. Shortly before the proclamation of Congo's independence, many of them were rushed to Belgium.

In 2018, then Prime Minister Charles Michel apologized on behalf of the Belgian state to these mixed-race children and their mothers (see below).

The outline of the future commission should be much broader, shedding light on all aspects of Belgium's colonial history. The cautious nature of King Philip's speech - regrets, not apologies - could be explained so as not to encroach on the investigative work to be carried out by the future commission. It is, however, a further symbolic gesture in favour of in-depth work on colonial history, and a sign that the Belgian state now intends to tackle this.

A COMPLAINT FOR CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY FILED AGAINST THE BELGIAN STATE

Five women who are among the Congo-born Métis children decided to file a complaint against the Belgian state, believing that the apology made by Prime Minister Charles Michel in 2018 was not enough, revealed three Belgian media, RTBF, Le Soir and Le Vif, on 24 June.

The introductory hearing will take place on 10 September. The complainants are each claiming a provisional sum of 50,000 euros from the state, pending the appointment of an expert who will assess the moral prejudice suffered. "Asking for forgiveness is easy. But I'd like the State to know that it destroyed us morally, physically. Every person has a right to his or her identity and we don't have one," one of the complainants told Le Soir.

Under the colonial administration, from 1908 to 1960, many mixed-race children were segregated in the Congo. These children were born of the union of Belgian men who, at the beginning of colonization, arrived alone and lived, outside of marriage, with Congolese women called "housewives". Some 12,000 "children of sin" were uprooted from their original homes and placed in orphanages that were run by missionaries, where they were considered "children of the state".

On the basis of official documents, the five complainants intend to point out that, until 1960, Métis children were removed from their African families to be placed in these orphanages. They will point out that not only were Métis children segregated, but that Belgian government officials and territorial agents searched the villages for some of these children who had escaped abduction, in order to take them away from their mothers and place them, like the others, in orphanages.