The explosive letter was released on 3 October. The unforeseen acknowledgment sent shockwaves, even being met with disbelief by relatives of one of the victims. The former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)’s admission – who, four years after signing a peace deal with the government, claims responsibility over three political murders – underscores how fragments of truth regarding some of the great unsolved mysteries of Colombia’s 52-year-long armed conflict are finally emerging.

It also creates a gigantic challenge for the Colombian transitional justice system, which was built on the idea that several judicial and extra-judicial institutions should work together comprehensively to prosecute the gravest atrocities and respond to the country’s 9 million victims. Until now, each has mostly operated on its own. The task of clarifying these three political assassinations is highlighting the downside of not working hand in hand.

Three unsolved mysteries

The three cases FARC are belatedly owning up to are among at least 274,139 murders in connection to the armed conflict since 1985, thousands of which remain in outright impunity.

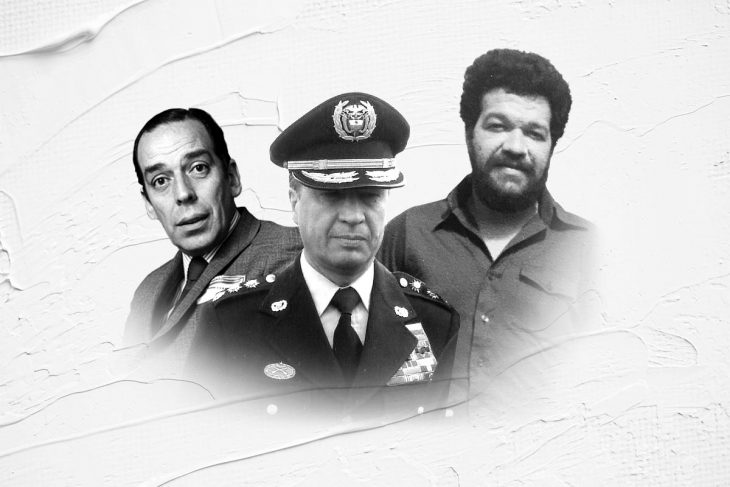

Álvaro Gómez Hurtado, a conservative icon who came in second in three presidential elections and is considered one of the brains behind Colombia’s landmark 1991 Constitution, was murdered on November 2, 1995 as he left the Bogota university where he taught. Fernando Landazábal Reyes, a retired Army general who was Defence Minister during the 1980s, was murdered after leaving his house in Bogota on May 12, 1998. And Jesús Antonio Bejarano, an economist and former peace negotiator who was instrumental in the successful talks leading to the demobilisation of the M-19, Popular Liberation Army (EPL), Workers’ Revolutionary Party (PRT) and Quintin Lame Armed Movement guerrillas in the early 1990s, was killed on September 15, 1999 in a corridor of Bogota’s National University.

Ironically, all three had devoted significant efforts to reflect on peace when they were killed. Gómez, known for his staunch anti-corruption rhetoric, preached for years on the need to reach “an agreement on the essentials” to end senseless violence. ‘Chucho’ Bejarano, who led doomed peace talks with FARC and the National Liberation Army (ELN) in Caracas in the early 1990s, was working on a document for the Ministry of Defence, contemplating different scenarios for both conflict and negotiation. And General Landazábal had just published a book titled Time for Reflection, in the epilogue of which he pleaded “that in Colombia the bells no longer toll for the souls of the dead, but for the advent of peace.”

“A window of hope opens, after 21 years in which the case didn’t advance one bit. Nobody was ever arrested, nor is there anything that shows that the state’s investigative machine was placed at the service of this case,” says Eduardo Bejarano, who was 27 years old when his father was murdered. “There is a ray of light to find a truth that the state was never interested in unearthing”.

The criminal justice’s longstanding debt

All three cases share another trait: the inquests into their murders gathered dust on the shelves of ordinary investigating authorities for more than two decades. In a country where opponents of the peace accord contend that the transitional justice was designed to shield former FARC members from serving prison sentences, given that they can obtain more lenient sanctions if they own up to their crimes, contribute the truth and redress victims, the debt of the ordinary criminal justice system is often overlooked.

General Landazábal’s relatives say they have been contacted by the attorney general’s Office, in charge of the criminal investigation, only three times in 22 years. A few days after his murder, two female investigators visited their family home. “They told us we’d be dealing with them very often. We never heard from them again,” says his daughter Olga Landazábal, who even remembers the white car they drove.

Two years later, they were summoned to the institution’s central office, where Olga recounts being asked to tell them under oath who had been responsible for her father’s murder. “I was livid. As a victim, I came here so you could tell me,” she recalls replying. Finally, a decade ago she met with a couple of investigators who told her that if new elements weren’t attached, the case would probably be archived. “I felt that they wanted to erase my father from this country’s history, as if he’d never existed,” Olga says.

Eduardo Bejarano shares a similar tale of frustration, citing frequent rotations of criminal investigators and an absence of answers from several attorney generals. In 2016, he discussed the case with then deputy attorney general – and former peace negotiator – María Paulina Riveros, who confirmed the case was stagnant and promised him to reactivate it. She resigned in 2019 and Eduardo says he hasn’t had any further news.

“FARC must explain their reasons to kill”

Both families see FARC’s letter as an opportunity for the long-awaited full truth to emerge.

“I’m not interested in homages. The only morally acceptable homage to my father’s memory is the truth: a truth grounded on facts and evidence,” says Bejarano, who vocally supports the transitional justice’s work but demands a higher standard of truth from FARC. He is particularly concerned over a press interview in which former rebel commander and current senator Carlos Antonio Lozada provided details on the commandos tasked with Gómez and Landazábal’s murders, but argued that Bejarano’s father was killed by “a different structure that I cannot provide details about.”

That missing truth takes the form of specific questions they seek answers to: who gave the order, how did they plan the crimes and, above all, why.

“Why was my father uncomfortable? Was it because he said truths that were embarrassing for FARC? Because at the time they were in a peace negotiation (with Andrés Pastrana’s government) tailored to their strategic objectives, with neither agenda nor methodology? History showed that the only thing the failed Caguán talks achieved was FARC’s military and financial strengthening. My father warned against the consequences of a poorly planned process,” says Eduardo, a political economist who works on improving labour conditions in coffee and palm oil plantations. Other possibilities he’d like FARC to address include whether they despised his father for his role in the failed 1992 peace negotiation or taking up the job as chief of the country’s largest agro-industrial guild. “FARC must explain to us their reasons to kill him,” he says.

Landazábal’s family is similarly puzzled by why FARC would consider their father a threat, way after he’d retired and left the political scene. “The million-dollar question is: why did they kill him 15 years later and not when he was actually fighting them? Why kill him at the age of almost 76, as he walked on the street alone, at a time when he had no troop command nor any of the social influence he once had?” asks his son Gustavo, a gastrointestinal surgeon and member of the Colombian Academy of Medicine. “I want them to explain to me what the genuine reason to kill him then was.”

In their eyes, it might be more understandable that FARC had animosity towards him in the 1980s, when he was a high-ranking military officer and penned 19 books on military strategy and the armed conflict, with titles such as Subversion and Social Conflict. And even if the three-star general was known as a defence hawk, he was, Gustavo says, a consummate reader who supported progressive public policies like agrarian reform and considered that social justice was central to achieving peace in Colombia.

Both families also want to know why it took two decades for FARC to admit their deeds, even though the 2016 peace accord paved the way for such acknowledgments.

JEP vs ordinary criminal justice

FARC’s revelation triggers an important methodological question: how to investigate these crimes that, beyond their perpetrator, could seem isolated?

That challenge falls on the shoulders of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, the transitional justice’s judicial arm whose work focuses on macro-cases detailing patterns, representative crimes and identifying those responsible for them, as opposed to a case-by-case logic. So far two of those macro-cases centre on FARC’s involvement in kidnapping and child soldier recruitment, while another one details extrajudicial executions by the military, and several regional cases document human rights violations by various actors.

The special tribunal, locally known as JEP, already summoned two FARC members – former commander-in-chief Rodrigo Londoño and Carlos Antonio Lozada – to preliminary hearings. It has not, however, chosen the route to investigate and prosecute these crimes, a call that justices on its Judicial Panel for Acknowledgment must decide on soon.

Although the JEP declined to discuss its internal deliberations on the matter, organisations like the Institute for Integrated Transitions have suggested possible routes and arguing that macro-cases should not focus only on repetitive behaviours, but also on illuminating FARC’s military goals or their modus operandi. One option could be a macro-case focusing on actions seeking to destabilise democracy, given that all three victims were political and social leaders. There is broad material for such a choice: at least 175 mayors, 543 local councilmembers, 28 departmental assemblymen, 16 lawmakers and three governors were murdered while holding public office between 1984 and 2014, according to a National Centre for Historical Memory report. It isn’t known how many of them were killed by FARC, but it’s likely a significant number.

Whatever the JEP decides, it will still get some criticisms from victims. Álvaro Gómez’s family already filed an injunction against the tribunal, contending that it has denied them access to information concerning his murder. Gómez’s case is particularly sensitive: president Iván Duque, a frequent critic of the transitional justice and an alumnus of the university founded by Gómez, asked the new attorney general to untangle that investigation earlier this year. The attorney general’ office has already summoned the same two FARC defendants to testify, potentially setting up a clash of jurisdictions. Members of Duque’s party, like senator Paloma Valencia, are pressuring for the case to remain in the ordinary criminal justice system, arguing it has a better chance of success than the JEP.

Another issue complicates matters further: Gómez’s family believes former president Ernesto Samper and his erstwhile minister Horacio Serpa (who died last Saturday) ordered the assassination. Their main concern is that a JEP investigation would concentrate exclusively on FARC – who described Gómez as “a military target and class enemy” – and exonerate the political rivals they believe were responsible. Neither Gómez’s son nor his nephew, who serves as the family’s lawyer, responded to Justice Info’s requests for interview.

To be together, or not to be

More broadly, investigating these three murders is testing the ability of the JEP and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the two cornerstones of Colombia’s transitional justice, of working together.

So far, both institutions have tried to respond to FARC’s surprise announcement separately. The JEP decided to respond publicly even before contacting the victims’ relatives and caught the TRC by surprise, according to two knowledgeable persons. Each institution then devised its own response: the JEP summoned its first defendants, while the TRC held a public act of contrition last Friday in which Lozada asked Bejarano’s relatives for forgiveness. The fact that FARC told the JEP about their decision to own up to these assassinations with one day’s notice and hinted that the press knew about it already made things more difficult.

The whole point of designing both judicial and extra-judicial mechanisms a part of a comprehensive system, was that the JEP – which has a 15-year mandate – could formally investigate and prosecute, while the TRC – about to finish the second of its three-year mandate – incentivises a truth-telling process that doesn’t involve legal consequences for those who volunteer information. Doing so would ensure victims won’t have to share their story repeatedly and would allow transitional justice to respond to unfolding developments – like FARC’s surprise admission – more methodically. But this implies coordination.

“The comprehensive nature of the system is crucial in order to respond as best as possible to victims, giving meaning to such a painful past and meeting society’s demands, amid a limitation of resources and time. The judicial scenario is insufficient on its own, as are the extra-judicial and administrative reparations. The only option is for all of them to work together,” says Mariana Casij, a researcher at the Institute for Integrated Transitions.

Lack of coordination has resulted in a series of blunders already. The JEP clashed with the smaller Unit for the Search of Disappeared Persons, over who should exhume the remains of several extrajudicial execution victims identified in a cemetery in Dabeiba, as well as with the government’s Victims’ Unit over its competence to order collective redress measures. In a similar vein, the TRC has organised hearings on matters being investigated by the JEP, such as a conversation with former presidential candidate and FARC victim Ingrid Betancourt on kidnappings, which the tribunal’s investigators learnt about through the press. These impasses underscore that the transitional justice system’s coordination committee isn’t functioning properly.

Still, the Landazábal and Bejarano’s families have high expectations on what the transitional justice can find, after years of uncertainty. “It’s hard to speak about things we haven’t heard yet. We want FARC to answer our questions, so we can understand what happened and why,” says Gustavo Landazábal. “I feel the moral need to listen to them, even if I’m not entirely sure the full truth will emerge,” says his sister Olga. “We’ll have to wait, because this will take more than just a couple of weeks. They’ll have to provide proof and the JEP will have to corroborate it rigorously”, says Eduardo Bejarano.

This Tuesday, FARC revealed that they were also responsible for a failed attack targeting vice-president Germán Vargas Lleras and another letter bomb that severed two of his fingers in 2002, showing that perhaps a cascade of admissions is finally beginning. The question is if Colombia’s transitional justice institutions will tackle them together, to bring long-awaited answers to the country’s millions of victims, or in a divided way.